Music Review: Tchaikovsky and turbulence go hand in hand

The Los Angeles Philharmonic’s multifaceted TchaikovskyFest has thus far weathered political incident. That is to say, nothing happened Friday night at Walt Disney Concert Hall to land performances of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto and Second Symphony on the front page or in the international spotlight.

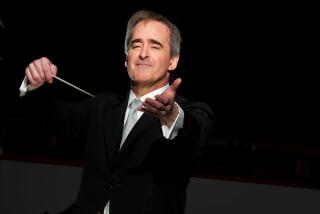

The concert, performed by the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela (sharing the festival with the L.A. Phil) and conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, did draw an assembly of demonstrators in front of Disney. They carried candles and displayed placards in sympathy with the current mass demonstrations in the streets of Caracas and other Venezuelan cities. Signs called for Dudamel to speak out against President Nicolás Maduro and the reports of his administration’s human rights violations, something the conductor has answered with blanket opposition to all violence and oppression.

Although there were no disturbances inside or outside Disney, musical incident was another matter altogether. The 11-day festival, which began Thursday night with Tchaikovsky’s chamber music and continued through the weekend with Dudamel-led concerts by the L.A. Phil and the Bolívars, will not be able to avoid politics or turbulence.

RELATED: L.A. Philharmonic 2014-15 season includes Dessner, Cerrone works

Tchaikovsky demands it. The times demand it. Dudamel’s contention is that music can serve as a lifeline for his troubled country, where the lives of hundreds of thousands of children and their families are sustained though the power of music education supplied by El Sistema, a state-supported agency. Now, in performances intense, hopeful, powerful, agitated and profound, Dudamel is attempting to make Tchaikovsky stand for something.

The main body of the festival is the composer’s six symphonies. The last three are performed and recorded to distraction. The first three are generally ignored outside of the occasional Tchaikovsky symphony cycle. Friday morning Dudamel conducted the First and Sixth (“Pathétique”) with the L.A. Phil, preceding the Bolívars’ evening performance of the Second along with the Violin Concerto, a chestnut.

These scores, familiar or not, remind us of just how effectively Tchaikovsky’s melodic style has long influenced musical life. His tunes have been turned into pop songs, appropriated by film composers and inspired an industry of musical rip-offs. The composer’s placing his heart within less than a millimeter from his sleeve is a long-standing subject of contention in music history.

In the end, though, the turbulence is what brings us back to Tchaikovsky. You think you know exactly what Tchaikovsky is feeling every second. One movement of a symphony he is excitingly up, the next plunges deep in depression, and, as with any roller coaster, the more harrowing it is, the better.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

But do we really know Tchaikovsky? A font of contradictions, he was his country’s most famous composer, yet notoriously insecure. He was a musical nationalist who also Westernized Russian music. He suffered extravagantly, particularly in his torment over his homosexuality, yet he could also be callously discriminatory (supporting, in particular, Russian anti-Semitic legislation).

The three symphonies heard on Friday stirred up a great deal. On the most obvious level, Friday morning’s pairing of the ambitious, rambling “Winter Daydreams,” as the First is known, and the “Pathétique” revealed a long journey traveled. Rudimentary ideas in the early symphony reach a searing conclusion, Tchaikovsky’s last and greatest.

Dudamel had a certain amount of fun with the First. With the “Pathétique,” though, he found a spellbinding degree of nuance. When he conducted this symphony during his first season as L.A. Phil music director, he sought extreme immediacy, digging for meaning.

Friday, in one of the most probing performances Dudamel has yet given in L.A., he appeared more trusting, letting the music speak for itself. Four years ago, Dudamel had boldly participated in Tchaikovskian hopelessness in the Finale; Friday, he stood ever so slightly back and looked on with compassion.

With the Bolívars, the mood was very different, and not only because of the demonstration or the worsening situation in Caracas that day. This is the biggest and most powerful major orchestra in the world, and that alone creates a unique dynamic.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

That muscle was apparent the night before when the Símon Bolívar String Quartet (the orchestra’s principal string players) performed Tchaikovsky’s First String Quartet with exceptional vibrancy. The sheer sonic energy seemed to have an effect on a sextet of L.A. Phil string players, who followed with an arrestingly forceful performance of the composer’s “Souvenir de Florence.”

In Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, though, soloist Alina Pogostkina was disappointingly introspective and fidgety. Dudamel held back his Bolívars, but that was like caging an eagle.

The Second Symphony is titled “The Little Russian” — Little Russia being, in 1879, the Ukraine — and the score is big Russia’s celebration of Ukrainian folk song. Dudamel let the eagle soar. The orchestra here numbered around 200. The playing was not always tidy; rather, the performance was an exuberant exposition of might.

Was this, then, a rallying of the fervent power of the people in solidarity with the demonstrations in Ukraine against its becoming a new little Russia? Does this imply idealistic, competent young Venezuelans (the Bolívars range from 17 to 31) taking control, a stirring performance stirring things up?

If the demonstrators return for further Bolívar concerts Monday, Wednesday and Sunday, I suggest the orchestra invite them into the hall to hear the concert. Then start a discussion.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.