Why Oscar Castillo’s photos of Chicano life and protest are essential for understanding L.A.

If you have ever seen a photo of Chicanos protesting in late 1960s or early ‘70s Los Angeles, chances are it may have been taken by Oscar Castillo.

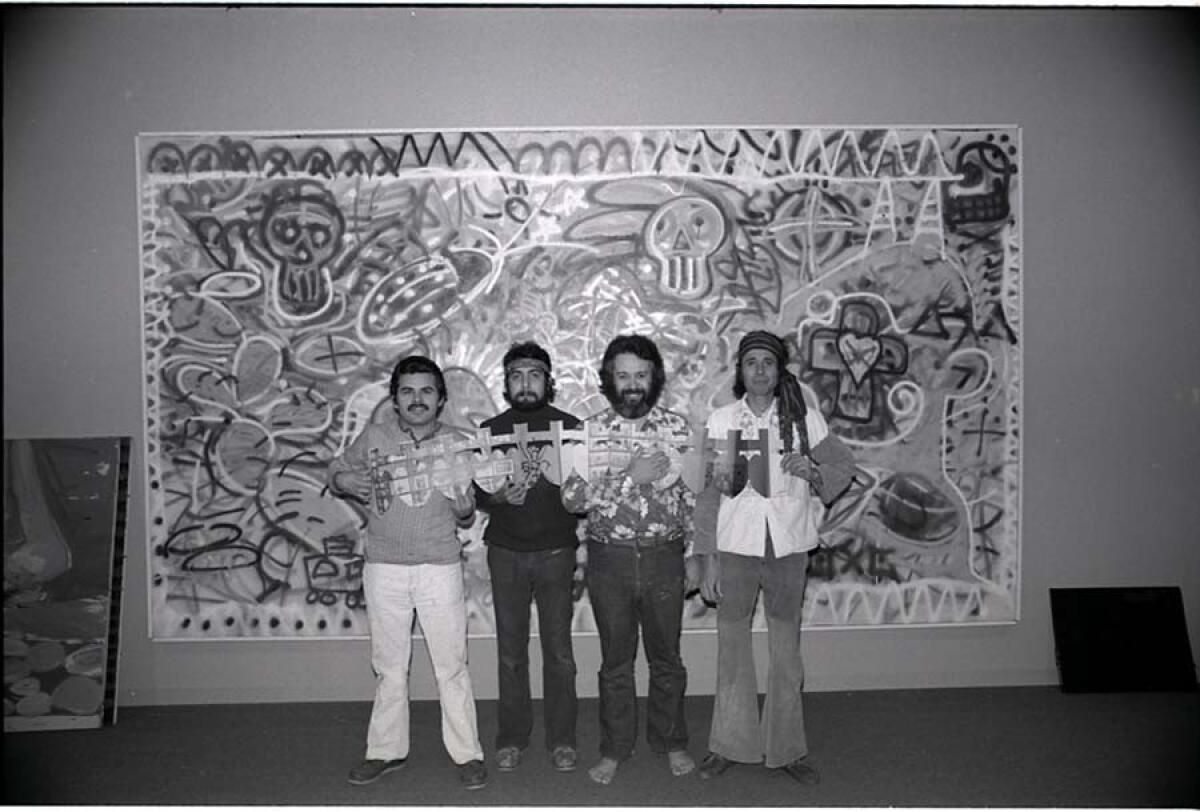

Iconic images of Mexican Americans marching down Whittier Boulevard protesting the Vietnam War during the Chicano Moratorium in 1970 and portraits of Chicano artists at work are part of Castillo’s prolific output that has made its way into museum exhibits, scholarly writings and documentaries.

Much of how the public has come to remember that time period has been through Castillo’s camera.

“I had a personal need to do it,” Castillo says. “I never thought I was going to be well known for this. I never really thought I would be creating a legacy.” Some of those images have found a home in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. And a small selection of his work was recently on view at Avenue 50 in Highland Park.

He picked up photography in Japan, where he was stationed as a Marine. It was the colorful kimonos, expressions of tradition and culture, and the lively protests against nuclear weapons that drew Castillo’s eye. Japan was picture-perfect training for what awaited him in a mostly Latino East L.A., with protests against police brutality and folkloric dancers.

No image combines the two geographies better than an image of a mural of the Virgin Mary clinging to a destroyed building. For Castillo, it echoed some of the destruction and trauma he witnessed walking in Hiroshima.

As a college student at Cal State Northridge he had a double-major, in Chicano studies and fine art. He would quickly put those degrees to practice on the streets of Los Angeles. But beyond what he saw in Japan, it was his mother’s family photo album that truly influenced him.

“It was a form of entertainment,” says Castillo, who developed a sense of place and story thumbing through its black pages. “It has pictures of family but also people I’ve never met like my great-grandparents. We would look at them and learn about different people in the family and the stories that went with different people. I continue to use it as a learning tool.”

There’s a larger photo album in the form of an archive Castillo is helping manage at UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center.

“I still have 99% of every negative I ever shot” Castillo says. Those archives are being digitized for future exhibitions.

Castillo’s work proves both challenging and interesting for many scholars. “Some of it borders on journalism and some of it borders on fine art,” Castillo says. “Or it could be a mix of both.”

“He’s hitting the widest range, stylistically,” says Chon Noriega, director of UCLA’s Chicano Studies Research Center, “from fairly traditional portraiture to snapshot photography, to photojournalism. Then the range begins to move toward the surreal. He begins to look like three or four photographers.”

If we don’t do it, nobody else will, or they’ll do it wrong.

— Oscar Castillo on the need for Latinos to document Chicano L.A.

On a particularly scorching summer day on the Eastside, Castillo shows many of those photographs at Tonalli Studio on Cesar Chavez Ave. Inside, a transformation happens. A gallery of visitors quickly turns into a family reunion.

“I had people come in I photographed 40 years ago. Oh, there’s my cousin so-and-so. It made me feel closer to that community, and it reinforces a community feeling and a family,” he says. “They can relate to those historical events.”

Castillo has a way of making Chicano protests feel like a family photo album.

He slings a Nikon D600 over his shoulder in case a moment presents itself. He’s still a photographer, after all.

Weeks later, Castillo is pacing around Highland Park’s Avenue 50 Studio. The hum of the Gold Line a few feet away is muted by the growing chatter on his photo show’s opening night. Many with wine in one hand snap cellphone pictures with the other to be shared on social media.

SIGN UP for Mark Olsen’s weekly INDIE FOCUS newsletter >>

Times have changed. Castillo knows moments of culture and protest find their way in the Instagram river. You won’t find him there. For the 70-year-old photographer, those days are mostly framed and over.

“I’m older now,” Castillo says. “I think there’s a lot of younger photographers and I think it’s their turn.”

He’s mostly stayed away from photographing political rallies and riots.

“Life’s too short,” he says with a smile.

The retired Castillo may not be on the front lines of protests anymore, but the motivation for why he started continues to grow. “If we don’t do it, nobody else will, or they’ll do it wrong,” says Castillo about photographing and publishing Latino life in Los Angeles. “We have to get it out there.”

Castillo spends much of his time organizing and curating his life’s work for future exhibitions and publications. The challenge now is using the images to tell a complete story — just the way he remembers his mother’s family photo album.

Follow @stevesaldivar on Twitter

For more arts news read Carolina A. Miranda’s CULTURE: HIGH & LOW >>

RELATED STORIES:

‘Cuba 1959’: Burt Glinn’s defining photos of revolution sat unpublished for nearly 60 years

‘Lost Landscapes of Los Angeles’: Rick Prelinger’s new film of old home movies and studio outtakes

How the zonkey got its stripes: Long before Instagram, Tijuana’s tourist donkeys were camera-ready

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.