Review: Wallis Annenberg Center is a step forward for Beverly Hills

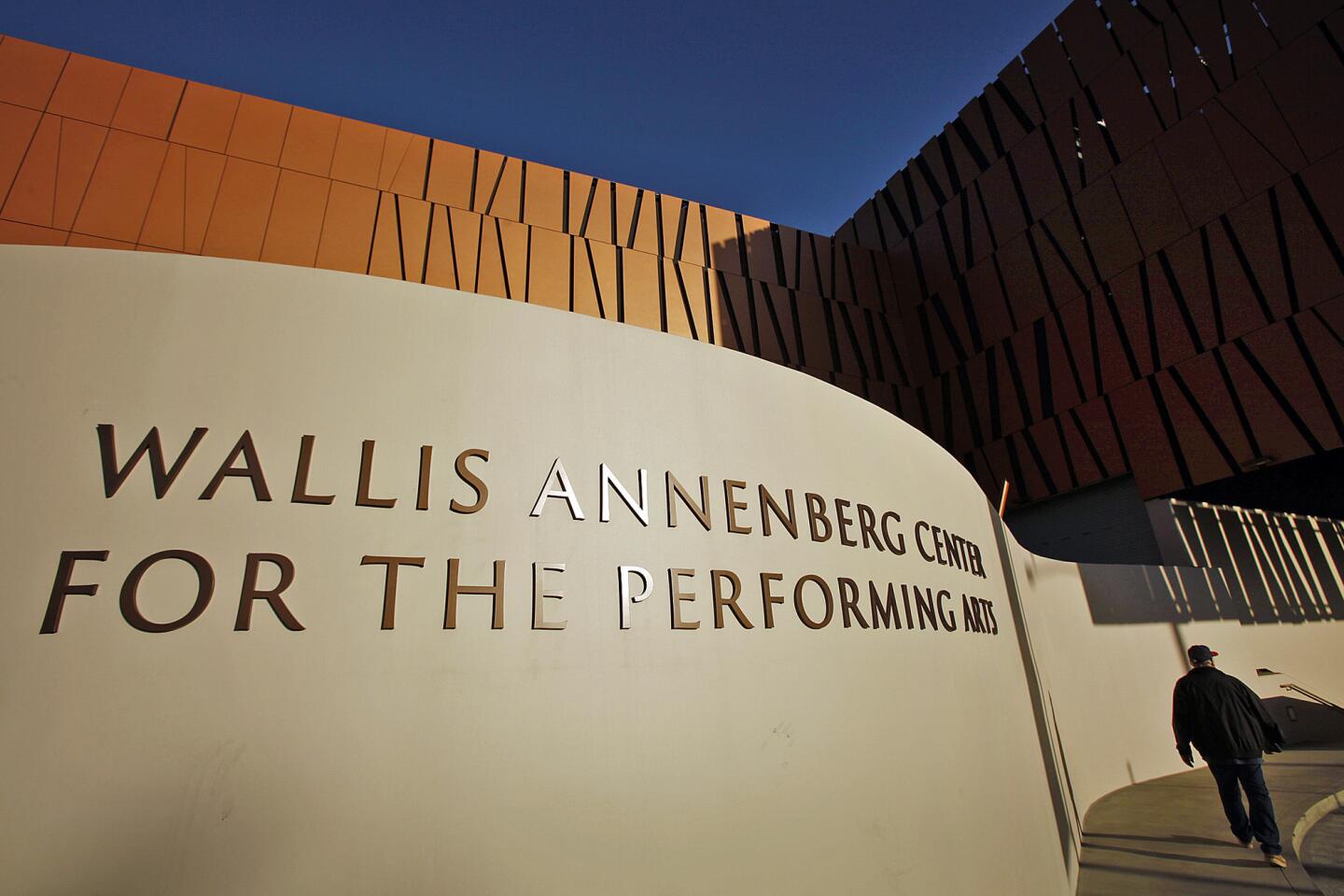

The new Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills, designed by Zoltan Pali and the firm Studio Pali Fekete, is a work of architecture that arrives with a long list of storylines attached.

In mixing historic preservation with unapologetically contemporary architecture, the $75-million complex, known as “The Wallis,” marks a step forward for Beverly Hills, a city that has not always treated its aging landmarks thoughtfully. Underwritten by $25 million in donations from the Annenberg Foundation, it is the latest chapter in a growing competition of architectural patronage between Wallis Annenberg and Eli Broad.

It’s also a clear example of how tricky it can be in Southern California to design a new building that’s architecturally sympathetic to its neighbors. On one side of the Wallis is the 1932 Beverly Hills City Hall, an eight-story tower designed by William Gage and dripping with historic ornament. On another is a 1965 Googie gas station, with a swooping roof, by Gin Wong and William Pereira. An architect could go crazy trying to find a respectful middle ground between those designs.

PHOTOS: ‘Never Built’ buildings and their real-life counterparts

But more than anything else the Wallis suggests that the balkanization of L.A.’s high culture, propelled mostly by our ever-thickening traffic, continues apace.

Even as downtown Los Angeles enjoys a renaissance and Walt Disney Concert Hall collects deserved accolades as it turns 10 years old, elsewhere we are seeing more and more support for the idea that every major pocket of wealth in Southern California deserves its own concert hall or performing arts center.

With lots of attached parking, of course.

Los Angeles has been a multi-polar metropolis, a city and region with many centers, for much of its history. But our cultural facilities have largely been concentrated downtown. It was one of the few ways in which L.A. stuck to a traditional definition of urbanism: When you wanted to hear a soprano or watch a major dance troupe, most of the time you headed downtown to Bunker Hill.

But now even that limited example of old-fashioned city-making — which has been propped up by generous public subsidy — is showing serious cracks, to judge by Southern California’s growing collection of well-appointed new cultural complexes.

RELATED: Christopher Hawthorne takes on L.A. boulevards

They include the $200-million Renee and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa, designed by Cesar Pelli and opened in 2006. Two years later we got architect Renzo Zecchetto’s Eli and Edythe Broad Stage ($45 million) at Santa Monica College, which has been so successful that it will soon get an extension by the firm DLR Group WWCOT.

The Broad was followed in 2011 by HGA Architects’ Valley Performing Arts Center in Northridge ($125 million). Soka University in Orange County has a new concert hall with acoustics by Yasuhisa Toyota, who worked on Disney Hall; Toyota was also a consultant for a forthcoming hall at Chapman University in Orange.

And now the Wallis. All these venues are essentially high-end community theaters — some of them very, very high-end — that reflect the increasing reluctance of major donors, whether they live in Brentwood or Newport Beach, to fight bad traffic to reach the Music Center downtown.

Under Executive Director Lou Moore, the Wallis raised the money for the complex in large part as a result of that gridlock-related frustration. Meanwhile, Beverly Hills — particularly its activist school board — has opposed construction of the Wilshire Boulevard subway, a transit route would make it possible to take a train downtown in about 20 minutes.

CHEAT SHEET: Fall arts preview

The centerpiece of the new complex is a stunningly restored post office. The Italian Renaissance building, designed by architect Ralph Flewelling in 1934, was closed by the postal service in 1998.

Its atrium, featuring Works Progress Administration murals by Charles Kassler, has been turned into a gleaming lobby for the Wallis. Rooms tucked away from public view hold dressing rooms, costume shops, offices, studios for a theater school and other facilities. The post office’s mail sorting room has been converted into a 150-seat black-box theater.

Directly south of the post office — connected to it by an underground passage but a separate structure as seen from outside — is a new building by Pali holding the Wallis’ 500-seat Bram Goldsmith Theater. Sunk 30 feet below ground to avoid towering over the post office, the structure is a simple box clad in a skin of red-orange cement panels. Facing west, where it opens onto a small garden, the theater has a glass façade.

The new building echoes the terra-cotta ornament of the post office. Its roofline appears to extend the cornice of Flewelling’s building. At the same time, Pali — whose firm is collaborating with Italian architect Renzo Piano on a new film museum in the old May Co. building on Wilshire Boulevard — hasn’t been afraid to make its cube-like form look entirely new.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

The resulting juxtaposition of old and new is not the kind of thing L.A. architects have traditionally had the courage to try often. But in recent years the strategy has become more common: Frederick Fisher pulled it off at the Annenberg Community Beach House in Santa Monica, as did CO Architects in designing a new entrance to the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park.

The space between the post office and the auditorium building at the Wallis is also carefully considered. A public walkway threads between them, leading pedestrians through the site.

The disappointing design for the auditorium itself, lined in undulating walnut panels, with odd blue lighting accents along the walls, is intimate but unresolved, even unsettled, architecturally. It seems to flow from a different architectural sensibility than the rest of the complex.

In terms of urban planning, Moore says the big move that made the Wallis possible was the decision by Beverly Hills to sink a new three-level parking garage, holding 481 cars, directly across Rexford Drive from the center, beneath the garden on the West side of City Hall.

There is already a large municipal garage on the other side of City Hall, on North Rexford Drive. It has 524 spaces. A parking structure on North Crescent Drive, two blocks south of the Wallis, has room for 720 more cars.

It’s possible many Wallis donors and audience members would balk at traveling even that short distance on foot. But the half-mile radius around the new hall may be as well served with parking structures as any place in L.A. County — which means as well as nearly any place in the country. In addition, the Wallis offers a valet service that brings cars to the front doors of the old post office.

It’s encouraging to see that the conventional wisdom about contextual architecture in Southern California is shifting and that clients no longer expect every new public building to slavishly copy those around it.

The idea that every new cultural facility needs an attached garage, and that patrons should never be expected to walk even two blocks after they park? That notion, unfortunately, may take a bit longer to fall out of favor.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.