Review: Disney Hall at 10: Season opener a magical, ringing salute

It looked on paper, with a few small exceptions, like an ordinary season-opening gala, the kind every major U.S. orchestra seems to practice these days — a jumble of Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Saint- Saëns favorites.

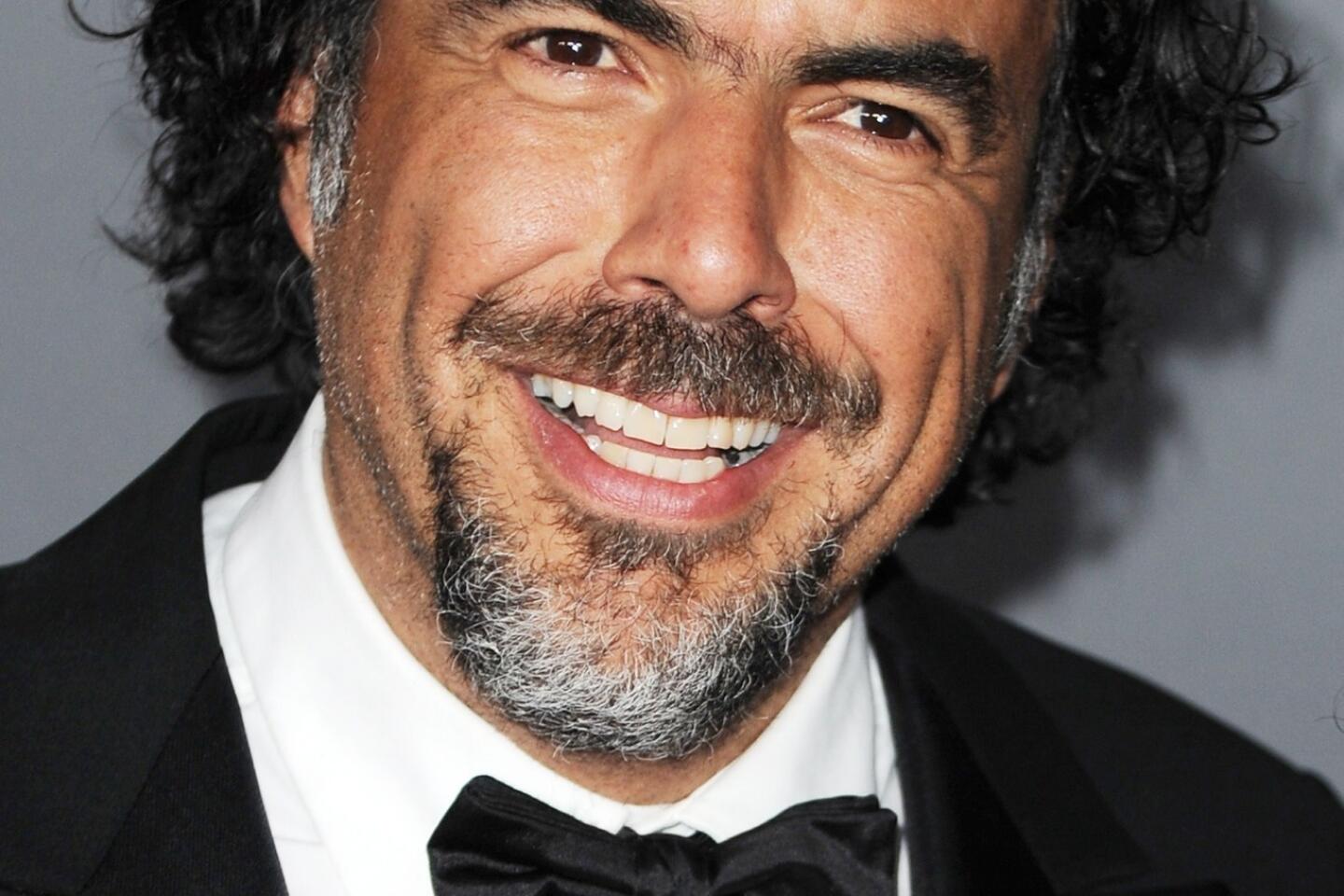

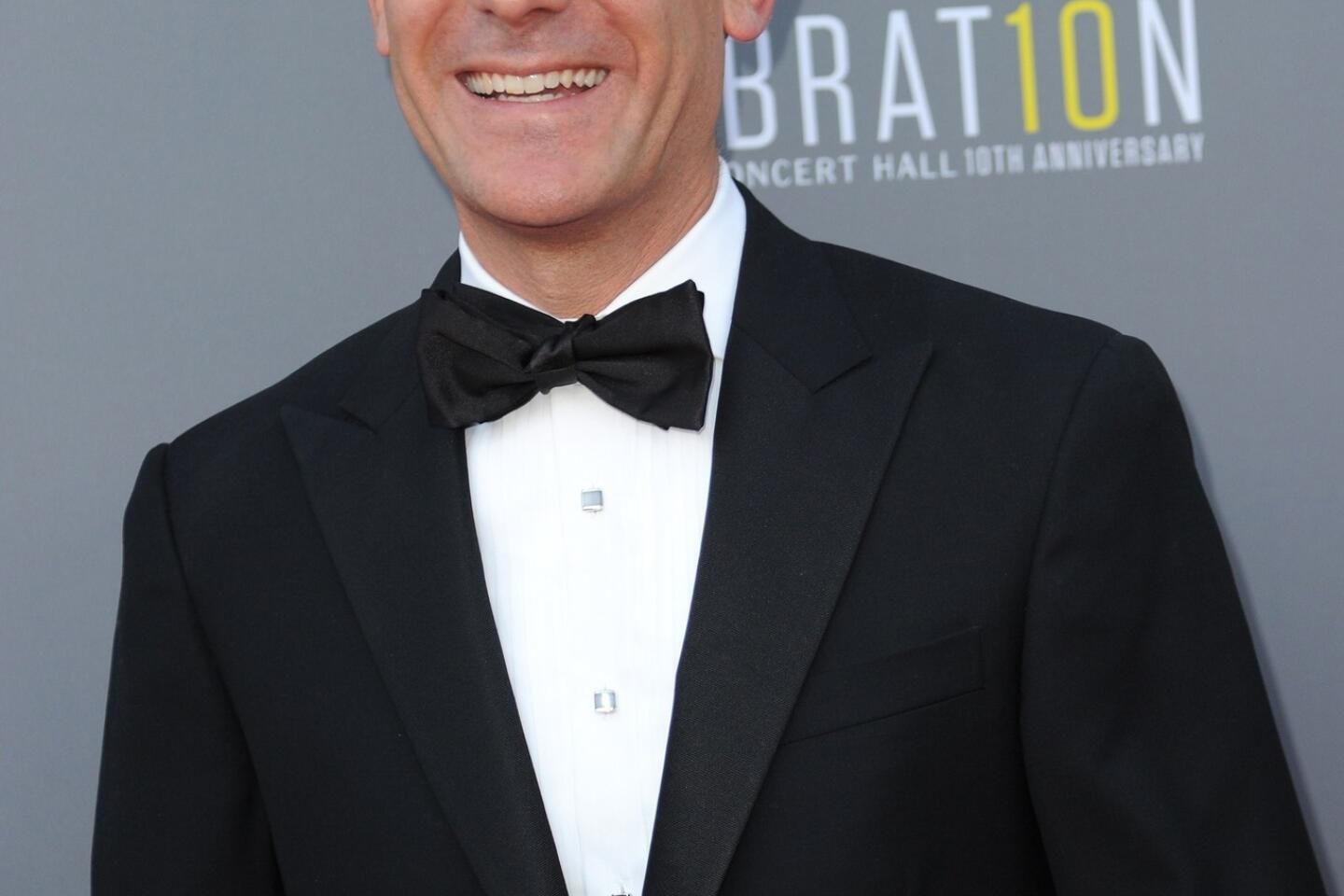

The superstar soloist was Yo-Yo Ma, who flew in after having been guest last week for the New York Philharmonic’s season-opening gala. Music director Gustavo Dudamel had jetted in himself practically at the last minute from performing in Japan.

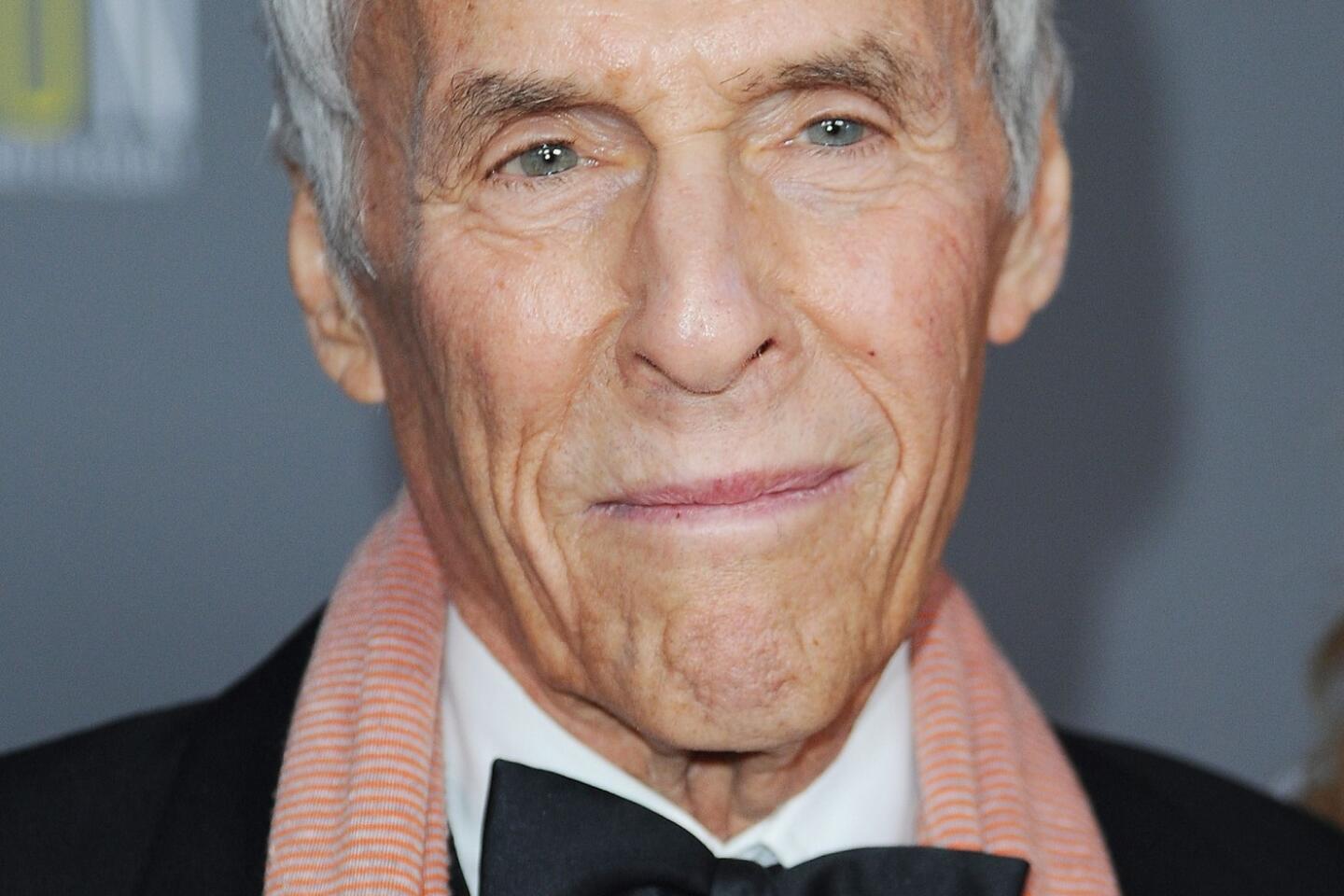

But Walt Disney Concert Hall is not paper. Monday night was meant as the celebration of the hall’s 10th anniversary, and the evening became an unexpected tribute to its architect, Frank Gehry. The ordinary very quickly turned into the extraordinary. That, of course, is the Disney magic.

Still, the L.A. Phil was taking no chances. In the lobby were projections of lively and revealing quotes by Gehry. Inside the hall, three screens shaped like sails were suspended overhead, further emphasizing (perhaps over-selling) the venue’s ship-like structure.

The installations were by video artist Netia Jones, who was also billed as the evening’s director. She turned the program into an 80-minute Disney-thon, illustrating and celebrating the hall, manipulating images throughout the program. Between pieces were more Gehry quotes, and recordings of him describing the neurotic yet inspired method of how he works.

This may have seemed like more of the L.A. Phil’s current obsession with screens, the orchestra already having caused a controversy over the summer with newly installed and brightly distracting video projections at the Hollywood Bowl. Certainly the screens in Disney robbed the interior of some of its architectural glory.

But the hall proved plenty resilient, especially when Dudamel began where no American orchestra has, before it, dared to go — with John Cage’s “4’33”,” the so-called silent piece. Disney is but a mile from where Cage was born in 1912, in Good Samaritan Hospital.

And for four minutes and 33 seconds the audience and orchestra sat quietly, instruments held as if to be played but not.

Ma sat in the soloist seat, looking intense. It is actually OK to relax. The audience was respectful, quieter than it, too, needed to be. The point is to simply take in your surroundings, become at one with them. When “4’33”” was over, Ma played the Prelude from Bach’s Third Cello Suite, and it was like a new person had entered the room and brought it to life.

Jones’ video was like yet another person added to the mix, however. She tried to fit image and music. In Tchaikovsky’s “Rococo” Variations for cello and orchestra, models of the hall and Ma’s highly expressive and soulful playing were at distracting odds.

I closed my eyes for Thomas Adès’ “These Premises Are Alarmed,” which was written for the opening of a hall in Manchester, England, in 1996. It’s an alarmingly wonderful four-minute piece with so much crazily fast details, and Dudamel made it so vivid, that enough seemed enough.

For the also-crazy Scherzo of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, Jones joined the struggle of Mahler’s music and struggle of building the hall, much of it with newspaper clippings documenting the troubled process of getting Disney built.

Dudamel went for high drama. He was fast, freer and more radical — and more brilliant — than even on his terrific recording of the symphony with the L.A. Phil.

Then, celebration. Dudamel ended with the finale of Saint-Saëns’ Third Symphony (“Organ”). It’s loud. It’s sentimental. It’s got great tunes. The organ, played with the exactly right amount of gusto by Joanne Pearce Martin, rumbled the floor and raised the air temperature.

The videos celebrated the orchestra, and they worked fabulously. Dudamel conducted Saint- Saëns in the hall, while Esa-Pekka Salonen conducted something else on the screen. This was the true Cagean moment. By not synchronizing sight and sound, both senses became heightened.

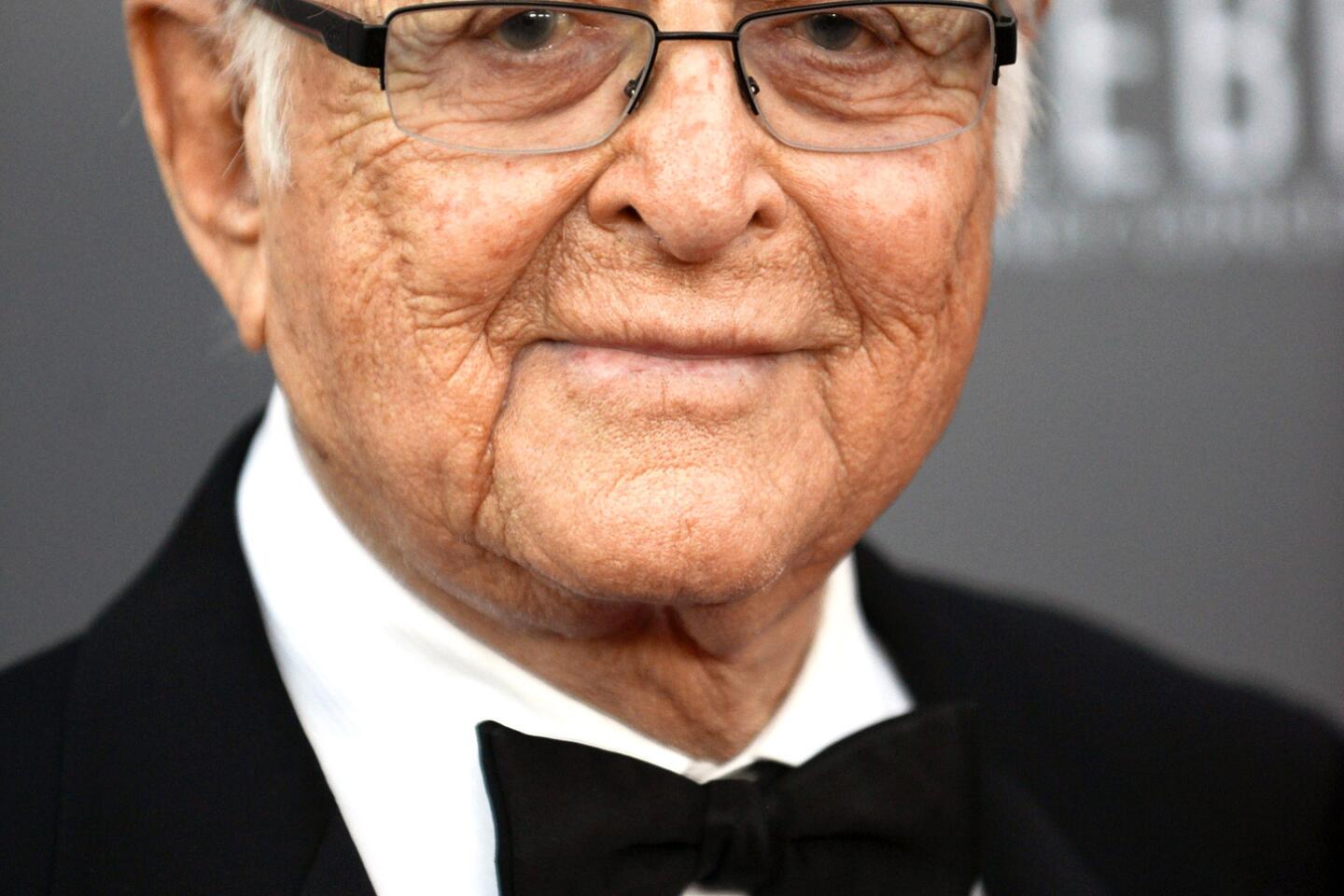

A parade of greats who have been part of the Disney decade were included — Zubin Mehta, Pierre Boulez, Simon Rattle, John Adams among them — were all fitted into Saint-Saens’ irresistible combination of sugar and thunder.

Does L.A. love Gehry? You need to ask? The final test of Disney acoustics were when Dudamel then brought the architect onstage and the crowd exploded louder than an organ and a hundred musicians could ever hope to.

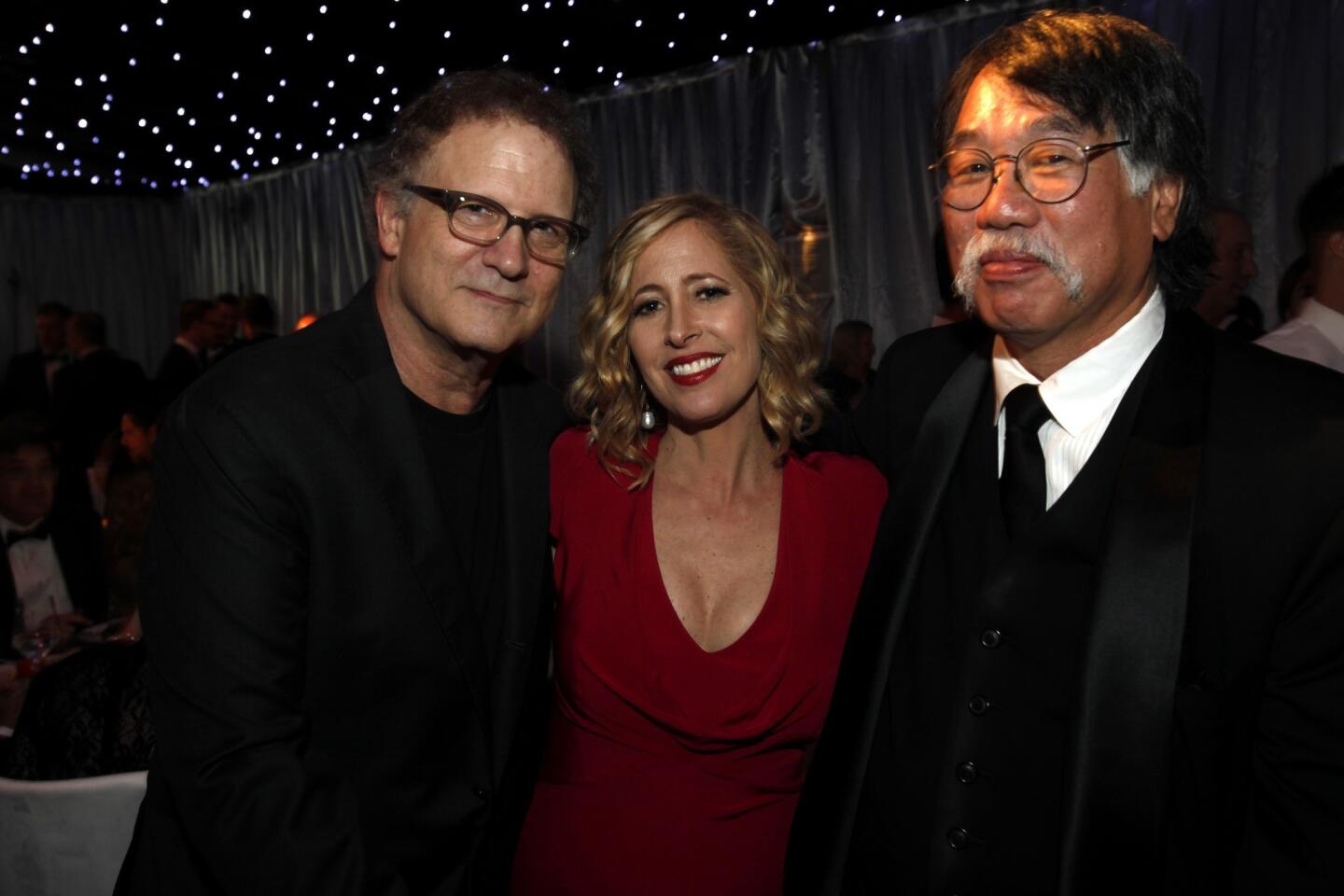

Still, you could hear individual voices. The acoustician Yasuhisa Toyota, who was in the audience, must have been proud and deserved to have shared some of the tribute.

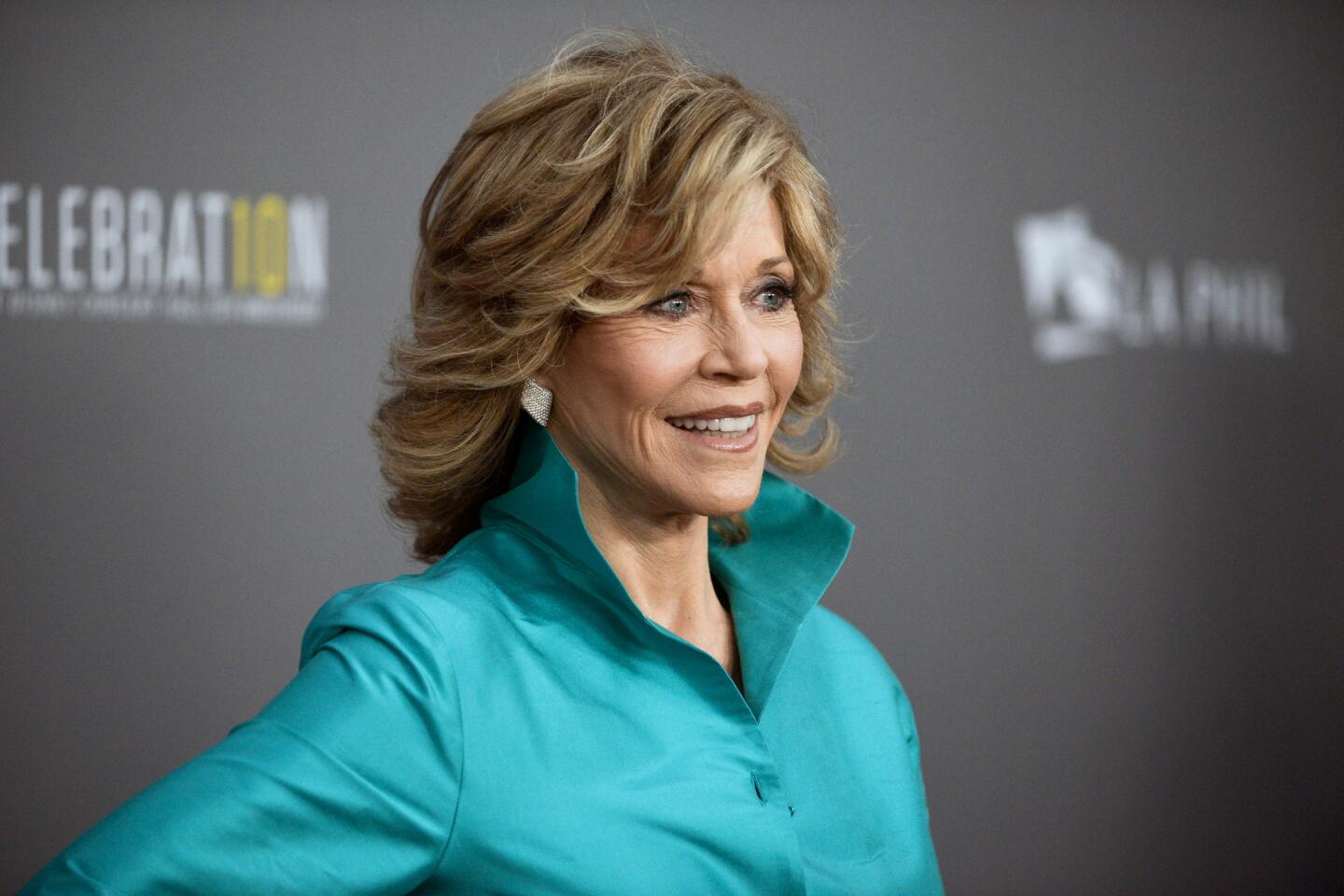

The final tribute, though, was to Lillian Disney, whose donations made the hall happen. Walt and Lillian were on the screens, and Dudamel led a syrupy arrangement of “When You Wish

Upon a Star.” Glitter stars snowed down from on high.

It was a happy night. Disney happy. Now, let the screens come down and the real business of Disney Hall begin.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.