The Getty’s ‘Cave Temples of Dunhuang’: How ancient desert outpost became remarkable global crossroads

If you think globalism is a modern phenomenon, head to the Getty Center and prepare for a mind-bending experience. Among other wonders in the landmark exhibition “Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road” is pervasive evidence of international, cross-cultural networking in medieval China.

The show focuses on the Mogao Grottoes, China’s greatest cache of Buddhist wall paintings and sculptures. Carved into the face of a cliff near the city of Dunhuang between the 4th and 14th centuries, the art-filled caves reside on the southwest edge of the Gobi Desert. But remote and isolated as it may be, Dunhuang grew up as an oasis on the web of ancient trade routes known collectively as the Silk Road, evolving into a political, military and economic center, as well as a gateway to the West.

As the exhibition reveals, the Silk Road facilitated more than the exchange of horses, camels, jewelry and silk. The historic thoroughfare hastened the spread of Buddhism from its birthplace in India and served as a conduit for other religions, foreign languages, technology and art — sometimes with surprising results.

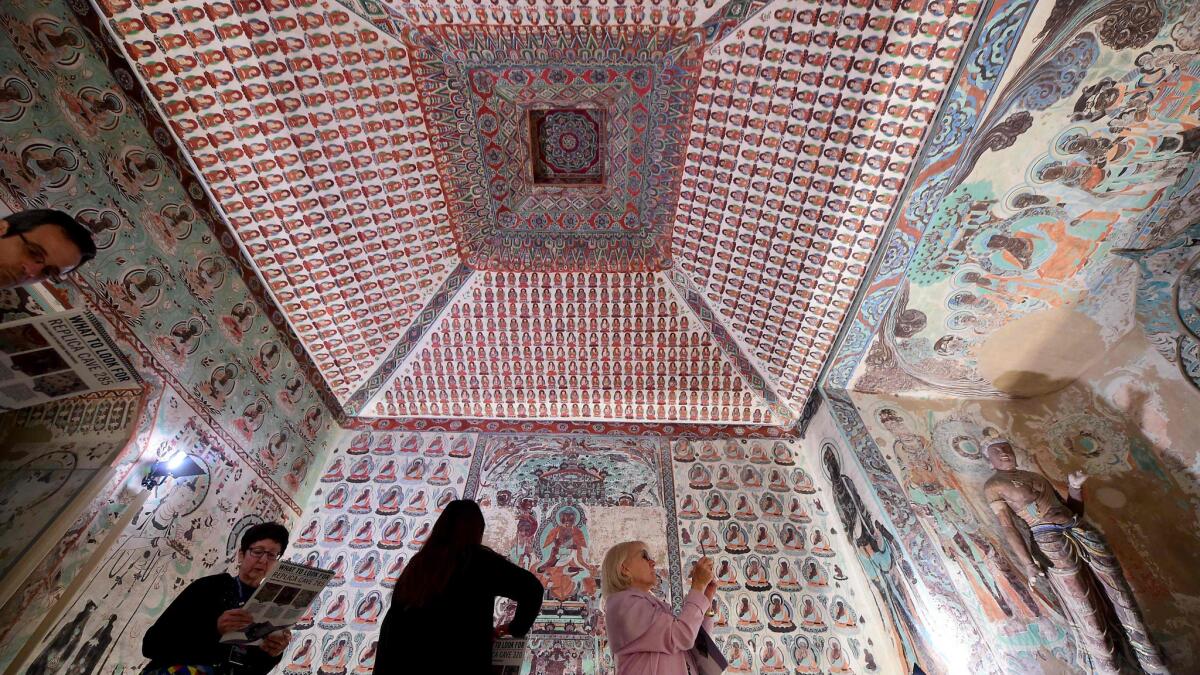

“Here’s a prime example,” said Neville Agnew, longtime leader of the Getty Conservation Institute’s work in China, as he entered a replica of Cave 285, one of three full-scale copies of Mogao’s richly decorated grottoes. “These are straight from India,” he said, pointing out wall paintings of Hindu gods, including the elephant deity Ganesha, in a sea of Buddhist figures. On an adjacent wall, the Chinese version of an Indian bodhisattva is busy protecting vulnerable travelers from bandits.

It may take a specialist’s eyes and knowledge to sort out all the cultural commingling in the replica caves, which were meticulously painted in China and installed in a temporary structure on the Getty’s plaza. Clues to the melting pot of ancient Dunhuang are easier to see in the galleries of the Getty Research Institute.

The 43 objects on view — rare manuscripts, drawings, paintings and embroideries — come from Cave 17, a long-sealed storeroom also known as the Library Cave. A multicultural mix of material includes Jewish prayers written in Hebrew, Chinese-language Christian texts and a Book of Omens written in Old Turkic script.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

Visitors also will see that bilingual documents are nothing new. A Sanskrit incantation is written in Brahmi and Sogdian — alternating lines, with the Brahmi version reading from left to right and Sogdian from right to left. A Tibetan accordion book with commentary in Chinese exemplifies the close relationship between the two countries during the 9th and 10th centuries, when Tibet was a ruling force in Dunhuang.

An intricately detailed copy of the Diamond Sutra, printed in 868 and thought to be the first complete book bearing a date, is a highlight of the show. There are also examples of extraordinary needlework in 8th century Buddhist textiles. But varied as the material is, impressions of a populace on the move pop up again and again. Marcia Reed, chief curator at the Getty Research Institute, pointed out early passports in the form of requests for safe travel and letters of introduction, including one prepared for a Chinese pilgrim on his way to India.

Apparently, Buddhist monks were often on the road. According to an essay in the exhibition catalog, early Buddhism was a proselytizing faith, and its advocates roamed far and wide. In an ink-and-pigment drawing called “Traveling Monk,” a long-faced man makes his way on foot with a protective tiger at his side and a pack of scrolls on his back. Another captivating drawing portrays a horse and camel as tribute animals. They are being led to their new owner, a powerful ruler who is expected to remember the donor kindly.

The wall paintings and sculptures in the Mogao Grottoes were commissioned by wealthy individuals and families who believed that establishing a Buddhist temple or meditation chamber would raise their stature and give them religious merit, to be used as needed. Merchants also developed a symbiotic relationship with Buddhism as religion and trade flourished.

Dunhaung may have had as many as 1,000 caves in its prime. Today they number 735, and of those, 492 are decorated. The last one was carved in the 14th century, when maritime trade routes expanded and traffic on the road through Dunhuang diminished.

Although the caves and their remarkable contents were never entirely forgotten, they were essentially abandoned for 400 years. A struggle between Britain and Russia for control of Central Asia awakened international interest in the area in the mid-1800s.

But no one was prepared for the discovery of the Library Cave in 1900 by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist priest and self-appointed guardian of the deserted Mogao Grottoes. The secret storage chamber was packed with about 50,000 manuscripts and art objects that would be deemed one of the richest finds in archaeological history.

British Hungarian archeologist and Sanskrit scholar Marc Aurel Stein, who was excavating in China on behalf of the British Museum and the British government of India, was the first Westerner to make off with a large portion of the treasure, in 1907. Apparently motivated by the need for funds to restore the caves, Wang sold Stein about 13,000 manuscripts, including the Diamond Sutra, and cases of art and artifacts. The purchase cost British taxpayers a mere 130 pounds (about $190).

Next came French scholar-explorer Paul Pelliot, who sent thousands of documents to France, and American art historian Langdon Warner, who acquired 12 sections of wall paintings and a sculpture for the Fogg Museum at Harvard University. The objects exhibited at the Getty Research Institute are loans from London’s British Museum and British Library and Paris’ Musee Guimet and Bibliotheque nationale de France.

Stung by the loss of its cultural patrimony, Chinese authorities established the Dunhuang Academy to conserve, manage and research the Mogao Grottoes. Since 1989 the academy has collaborated with the Getty Conservation Institute on projects including extensive work in Cave 85, intended to serve as a model for the preservation of wall paintings at Mogao and similar sites.

The “Cave Temples” exhibition, which commemorates the partnership, examines “one of the world’s greatest treasures,” said Tim Whalen, director of the Getty Conservation Institute. “We hope that the public comes away with a deep understanding of what this sacred, singular place is and how it functioned in its desolate desert setting. He wants visitors to see not only the artistic works created there but also “the complexities of preserving and conserving such a heritage site in the modern day.”

------------

“Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road”

Where: Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Through Sept. 4

Tickets: Free; timed reservations must be made on-site. Parking $15.

Info: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu/cavetemples

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.