After Guggenheim removes animal-related pieces from ‘Art and China,’ what’s left? More questions

When can a museum exhibition be defined by what is absent, rather than what is present?

When it’s “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the World” at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Just before the exhibition opened this month, the Guggenheim removed three pieces of art including a Huang Yong Ping installation that served as the exhibition’s centerpiece and its subtitle.

The museum had received thousands of phone calls, emails and letters from animal rights activists, including PETA and the ASPCA, protesting what they call the abuse of animals in some of the works. (Huang’s “Theater of the World” was to have live insects and the reptiles trapped in a survival-of-the-fittest habitat.) “People who find entertainment in watching animals try to fight each other are sick individuals whose twisted whims the Guggenheim should refuse to cater to,” PETA President Ingrid E. Newkirk wrote to museum Director Richard Armstrong. A Change.org petition charged that “the exhibit will feature several distinct instances of unmistakable cruelty against animals in the name of art” — and has garnered more than 800,000 signatures.

The Guggenheim quickly announced it was removing the works in question and issued a news release that said: "Although these works have been exhibited in museums in Asia, Europe, and the United States, the Guggenheim regrets that explicit and repeated threats of violence have made our decision necessary.” When contacted later, the museum declined to elaborate. (Neither the PETA letter not the Change.org petition threatened violence.)

The removal of the three works has raised accusations of censorship.

Since opening day, the public discussion about “Art and China” has been as much about this issue as it has been about the art. In consultation with the artists, the Guggenheim decided to present the framework of each missing work, almost as an object lesson.

“We saw the potential to turn the absence into a presence,” said Alexandra Munroe, the museum's senior curator for Asian art and lead curator of the exhibition, which was co-curated by Philip Tinari and Hou Hanru. “We saw this could be an opportunity to reflect on the themes of globalism, to reflect on our own times.” Munroe said the museum acknowledged “the questions that an institution has to face in presenting works from a very other culture. The whole purpose of this exhibition is to present other sensibilities, other conditions.”

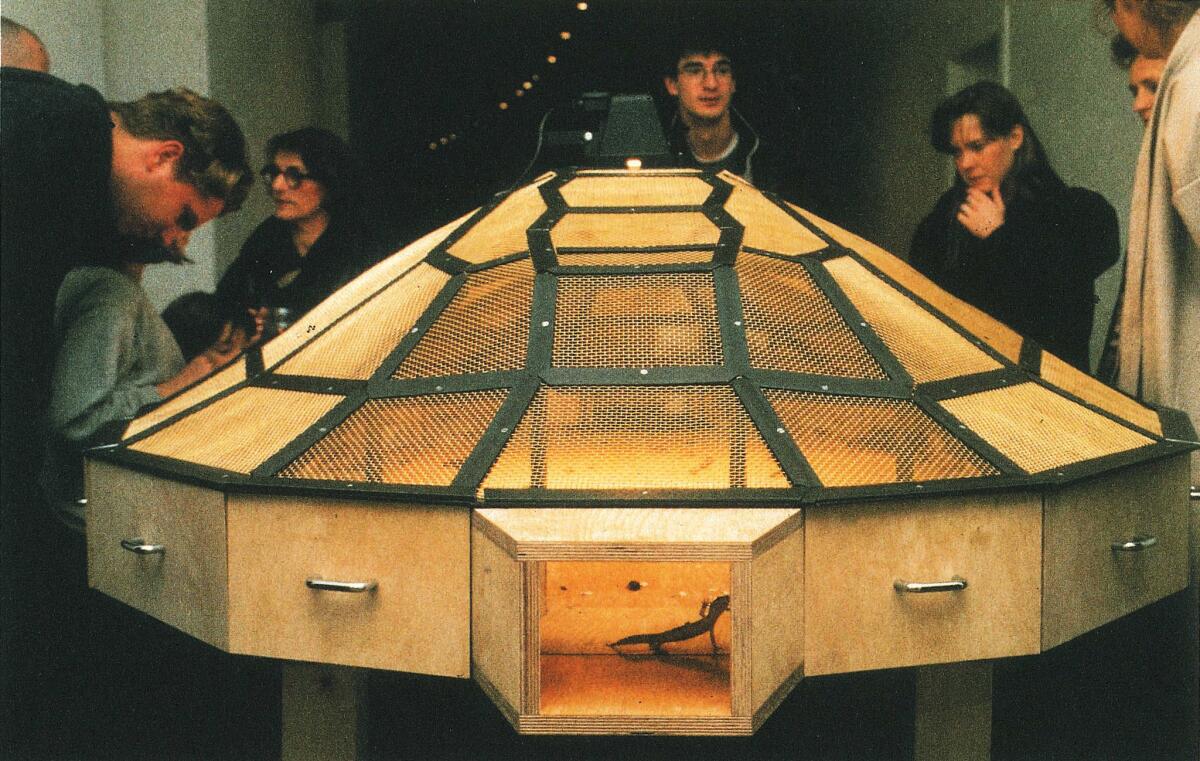

“Theater of the World” sits in the middle of a room near the beginning of the exhibition. The faceted box, now empty, is covered with a mesh top through which one would have seen insects and reptiles. When asked how he felt about his work being removed from the exhibition, Huang said: “Read my statement. I think that says it all.”

The artist’s statement chastises those who protested the work sight unseen. “It is said that more than 700,000 people are opposed to this work that involves living animals,” he wrote, “but how many of those people have really looked at and understood this work? Modern society (news media, online media) has engendered a new servility that makes people parrot each other.”

The other two excised works are videos: Xu Bing’s “A Case Study of Transference” (1994), midway up the museum’s spiral ramp, and Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s “Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other” (2003), located at the end. The monitor for Xu’s work is black, but it would have shown a performance in China featuring two pigs in a pen. One pig, covered with Roman letters, repeatedly mounts another pig covered with what look like Chinese characters. It can be interpreted as a crude metaphor for Western imperialism, but it is also a bit of a prank because neither the Roman letters nor the Chinese characters form real words.

More than 700,000 people are opposed to this work that involves living animals, but how many of those people have really looked at and understood this work?

— Huang Yong Ping, the artist behind "Theater of the World"

Sun and Peng’s work was presented in a Chinese art museum in 2003. Pairs of pit bulls are set on treadmills facing each other; each runs and snaps at the facing dog with increasing ferocity, barely kept apart by harness restraints.

Artists of the excised works were allowed to write an accompanying statement. Sun and Peng let a monitor showing only their work’s title and their names speak for itself.

Despite the missing pieces,”Art and China” remains an ambitious exhibition attempting to track the major socio-political changes in China through its contemporary art.

“No nation in modern history underwent such a total transformation as did China during these two decades,” Munroe writes in the accompanying catalog. “The artists in this exhibition see themselves as both agents and skeptics of this accelerated change.”

Museum Director Richard Armstrong said at the press preview that what some artists show “is not always pretty,” and while the three censored artworks have received so much media attention, “we have another 147 works in the show, and they’re all important.”

The starting point of 1989, Munroe said, comes from the landmark art exhibition “China/Avant-garde” at the National Art Gallery in Beijing. That also was the year of the Tiananmen protests, when hope grew behind a student movement calling for political reform — then was violently crushed by the military. Munroe also cited the launch of the internet, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War as signals of a new global order.

"Art and China" features some 150 works by 71 artists. It starts with a modest pile of dried pulp placed atop a piece of glass balanced on a wooden box, Huang’s “The History of Chinese Painting and a Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes” (1987/1993). The artist put two stuffy art-history texts, one in Chinese and one in English, in the laundry and pulverized them — in keeping with the artist’s Dadaist inclinations. In the 1980s he was a founder of the Xiamen Dada group, and while visiting France in 1989, the year of Tiananmen, he decided not to return to China.

Wang Guangyi’s “Mao Zedong: Red Grid #2” (1988) is a portrait of Mao in black and white, mysteriously and perhaps subversively behind a red grid. When a similar work was submitted to the “China/Avant-garde” show, authorities questioned the artist about the unconventional depiction. He cleverly replied that the work was a way of looking at Mao “rationally.”

The father of Chinese video art, Zhang Peili, is represented by two of his early pieces — one of a live chicken being washed during a bird flu scare, the other of a TV announcer reading from a dictionary, as if even something so banal could be read with the urgency of the evening news.

There are discoveries as well, such as a video of the performance “To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain” from 1995, done by an art collective. Usually, one sees this as a photo of naked bodies piled on a mountain top. The rarely seen video reveals the ritual of the 10 participants slowly taking off their clothes, then weighing themselves on a scale, before placing themselves on one another, presumably the lightest on top.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

Ai Weiwei and Cai Guo-Qiang, the two best known Chinese artists internationally, also weigh in here. Ai has several works, including the famous series of photographs from 1995 showing him dropping a Han period urn and letting it break into smithereens at his feet. On another wall is the list he compiled after the disastrous Sichuan earthquake in 2008 — a list of the children who died, he said, largely as a result of shoddy building construction.

Cai is here with one of his large-scale gunpowder “paintings” — works done with exploding gunpowder, plus ink and brush — as well a video from the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008

And yes, there appears to be only a few female artists here, including Lin Tianmiao and Ellen Pau (who is from Hong Kong). “In the period under review — 1989 to 2008 — the Chinese art academies were largely dominated by men,” Munroe said. “Given that our focus is on conceptual art practices — installation, video, performance — may have meant that we were not considering too many realist painters, including women. The good news is that the situation has changed dramatically.”

Also included are lesser known artists such as Xu Zhen. A video of the performance “Rainbow” from 1998 shows the long, thin back of the artist, and his painful flinching as a series of red handprints show up on the flesh. Xu deliberately edited out the hand slapping him, which makes for a shocking image of someone being beaten by an unseen perpetrator. Sometimes what’s invisible makes the most potent statement.

The exhibition will be traveling to the San Francisco Museum of Art in November 2018. Officials there have not yet determined whether they will show the contested works.

See all of our latest arts stories at latimes.com/arts.

MORE NEWS AND REVIEWS:

Can 11th-hour updates save Renzo Piano's Academy Museum?

A Baroque masterpiece , missing for more than a century, is hiding in L.A.

Carrie Coon, at the top of her game, returns to the stage where it all began

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.