Review: Thrilling new exhibition shows modern Mexican art is bigger than murals

In 1921, as the bloody, decade-long Mexican revolution drew to an exhausted close, the distinguished intellectual José Vasconcelos was named to head a new Ministry of Public Education. In that post, Vasconcelos was instrumental in making a fateful decision: There would be murals — public murals, funded by the state and painted on community walls as an educational tool.

As reflected in the national budget, Mexico’s post-Revolution government made its highest priorities spending for the military and for schools. The first would bring order, the second would bring education for all.

Successful self-government demanded both. An unfolding transformation from the socially stratified dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz to an egalitarian socialist ideal would be visualized — and sanctified — in magnificent civic paintings.

Ever since, the art of revolutionary Mexico has been synonymous with the sensational murals produced by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, the big three of the movement. Los Tres Grandes cast an enormous shadow.

More recently, the easel paintings of Frida Kahlo have been added as an essential codicil to the story, and she has gone on to eclipse the muralists in fame. But the extraordinary narrative begins with murals — a fact that has made for some difficulty in a larger understanding of the achievements of Mexican art in the first half of the 20th century.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art faced the daunting challenge when organizing “Paint the Revolution: Mexican Modernism, 1910-1950,” a sprawling — and thrilling — survey of paintings, drawings, photography and prints. There hasn’t been a show like this in more than 60 years. But, attached to walls, murals can’t move. So what is a museum to do?

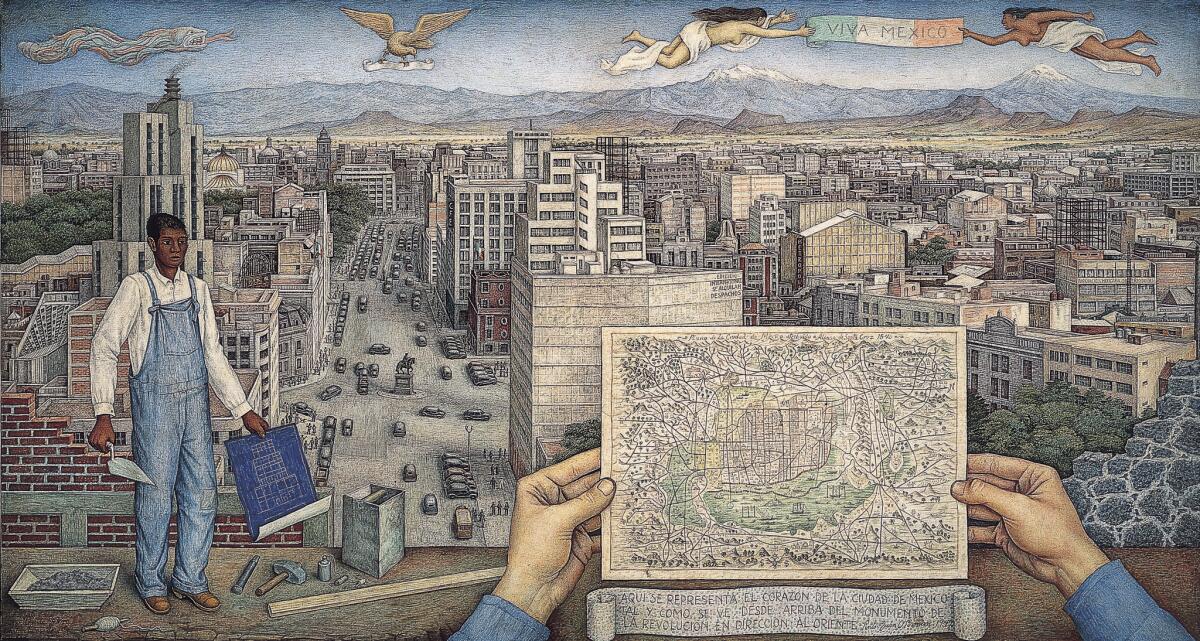

Take Rivera’s remarkable frescoes for the Neo-Classical courtyard loggia of the education ministry in Mexico City. They are divided into two themes: labor and fiestas.

A densely illustrated pictorial narrative of work and play — of battle, farming, workers’ co-ops, dancing, political protest and more — is united by a continuous crimson banner painted over the doors. “What we say to the rich and lazy is: If you want to eat, then work,” it declares. “Now all the underdogs have bread.” The banner is painted over imagery that ranges from Aztec to Masonic, rendered in wry imitation of stone relief.

The rhythmic regularity of the panels, each in the wall space between sets of double-doors leading to inner ministry offices, led the artist to conceive of the ensemble as a ballad. It’s an epic poem told in popular pictures and verse. The text is the lyric to the visual song below, sung in crowded scenes of men and women pushed up to the shallow picture plane.

But to hear the music, you must go to the mural. The mural cannot come to you.

In Philadelphia, the problem was addressed through digital technology. When I learned that video projections and big touch-screens would be used to articulate three murals, one by each of Los Tres Grandes, I was nervous. Even the finest high-tech format is still a reproduction. A fresco’s reflected light would be projected from behind, creating a wholly different effect, and without the visual tactility of painted surfaces.

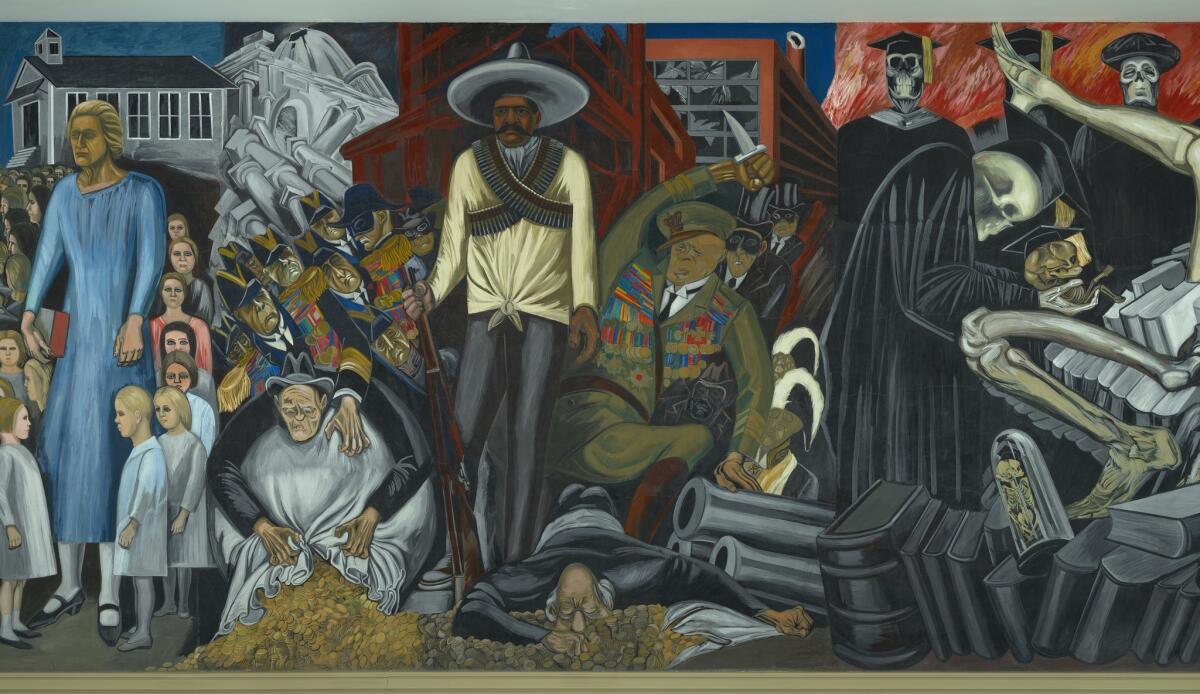

The show’s ambitious mural examples are Rivera’s seminal masterpiece for the education ministry; Orozco’s cycle on American civilization painted for a library space at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., demonstrating Mexican Modernism’s internationalism; and, finally, the rabble-rousing theatrics by Siqueiros for a raucous stairwell mural in a union building, painted just at the time the artist also launched an unsuccessful attack on the Mexico City home of Leon Trotsky, the exiled former Soviet leader.

I need not have worried. The issue has been successfully addressed. The large, compelling digital reproductions are sequestered, shown in spaces adjacent to but distinct from galleries with actual art objects. And those objects — more than 275 works — are often riveting in their own right, while offering essential mural context.

Many of the 78 artists are not well-known in the United States. But the story of Mexican art during and after the Revolution is cogently laid out in five sections. An aesthetic wrestling match gets underway immediately.

Art was devoted to propagandizing for social causes, including the resuscitation of a submerged indigenous history that the Spanish conquerors sought to eradicate or bring to heel. Those figurative demands collide with the conspicuously Modern urge for abstraction. Modernism meets mexicanidad, shorthand for a distinctly Mexican flavor.

Hints of it are in Rivera’s “Adoration of the Virgin and Child” (1912-13), painted in Spain during the 14 years he studied abroad. A peasant couple, she with a basket balanced on her head and he holding a bowl filled with bread, dominate the foreground. They turn to witness a triangular, mountain-like apparition of mother and infant inside a jagged crimson halo.

Picasso’s Cubist spatial fracturing and the Fauve colors of Matisse are applied to a traditional, El Greco-style religious subject. The scene is bathed in the green, white and red of Mexico’s national flag. Rivera lived abroad during the revolution, but the painting claims for his own country a modernized version of a European spiritual theme.

Opposite the Rivera, sunrise breaks over a dark, jagged mountain range in waves and rings of vivid color in a 1916 painting by Gerardo Murillo. The mountain seems to have erupted in sprays of light. Volcanoes were the lifelong favored subject of the eccentric artist and theorist, who called himself Dr. Atl.

In the wake of independence movements, the rise of 19th century landscape painting in Europe and the Americas pictured new nation-states as natural. But in the 20th century Dr. Atl went underground.

His volcanoes tapped into the Aztec legend of Popocatépetl and Iztaccihuatl, the two peaks at the edge of Mexico City said to have been formed from a Romeo and Juliet story of passion and mortal transformation.

Dr. Atl’s volcanic landscapes parse the roiling miasma beneath Earth’s crust as an analogy for explosive inner turmoil, both personal and political — including revolution. He even mixed his resin and oil pigments with gasoline, a medium he dubbed “Atl color;” it prefigured Siqueiros’ subsequent experiments with modern industrial materials and techniques, including spray guns, plastics and auto paint.

Metaphorically, at least, Dr. Atl’s paintings might spontaneously combust.

Nearby, the first of the self-portraits with which Frida Kahlo would craft her own self-identifying image to the world, shows her as a Botticelli-like goddess dressed in wine-colored velvet before stylized blue waves. Painted in 1926, the year after a disfiguring trolley accident nearly killed her, it redefines bourgeois womanhood and beauty.

With an oversized hand gracefully held out before her, the deep décolletage of her dress makes the shape of her exposed flesh into a dagger. The hand of this artist will fight.

Works by fewer than 10 women are in the show. (There’s almost no sculpture, perhaps because it’s less conducive to a peoples’ propaganda.) Not until after World War II did women such as Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington come into their own, a demonstration of the limits on revolution-era freedom.

But Kahlo, a committed Communist, understood something better than her male counterparts. Obsessive, iconic self-portraiture was key to crafting a mythologized, cult-like identity — witness portrait-mad Lenin, Stalin and Mao.

The show has surprises. Among them are the photographic abstractions of Agustin Jimenez Espinosa, repetitive and machine-like geometric forms whose origins as ordinary objects defy easy recognition. They hold their own in a beautiful alcove of 23 examples of the grandeur pulled from details of ordinary daily life by such Modernist photographers as Edward Weston, Manuel Álvarez Bravo and Tina Modotti.

A philosophical war between competing artistic ideologies also broke out in the 1920s.

On one side were the Stridentists, today little-known, led by the poet Manuel Maples Arce. As one might expect from the name, the group upheld an almost authoritarian view of what was and wasn’t artistically allowed in the name of revolution. Often it translated into a rather dreary, unimaginative if sometimes brightly colored social realism.

On the other side were Los Contemporáneos. Their poetic, cosmopolitan viewpoint celebrated the free play of individual imagination, wholly outside industrial-strength Stridentism (and outside macho muralism, for that matter). That artists like Manuel Rodriguez Lozano and Abraham Angel were homosexual, their paintings shrouding folkloric themes of Mexican life within melancholia, might partly explain it.

A Lozano nude shows an anonymous Indian seated on a pillow inside a blank chamber. Her back to the viewer, her gaze fixed on clear blue sky outside a high window, she conveys a monumental yearning. Unlike Kahlo’s “dagger Venus,” she’s a solemn prisoner of her confined place in the world.

Not until the show’s end does abstract painting make an appearance — perhaps unsurprisingly in the Surrealist-derived work of European expatriates Wolfgang Paalen and Gordon Onslow Ford, fleeing World War II. Their organic shapes, buzzing power lines and spiny creatures literally made from smoke occupy the other side of an artistic planet from the grotesque, equally engaging caricatures of Hitler, Franco and Hirohito nearby — wartime propaganda broadsheets turned out by the People’s Graphic Workshop.

The engrossing show was organized by Matthew Affron and Mark A. Castro at the Philadelphia Museum and Dafne Cruz Porchini and Renato Gonzalez Mello in Mexico City, where it will be seen at the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in February. That it won’t travel to Los Angeles, home to the largest Mexican American community in the nation, is a major disappointment.

Sources say an offer was made to

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

ALSO

Martin Luther broke Europe in two, and Albrecht Dürer painted it back together

John McLaughlin, the most important postwar artist you don't know

Essential Arts: An immigration musical, self portraits fusing black and white, getting gender-bendy

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.