Tony nominee Savion Glover: Go ahead, call me a Hoofer

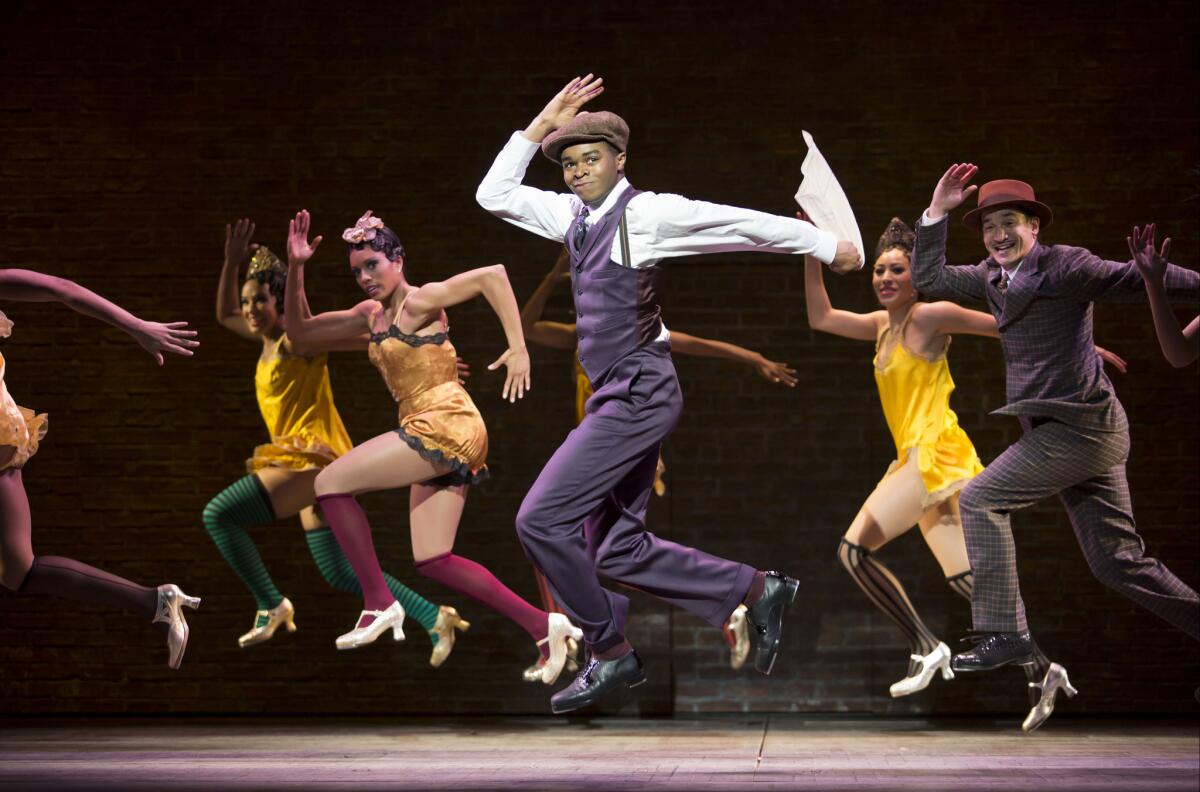

There is a galvanic moment in the new Broadway musical “Shuffle Along” when Audra McDonald, playing actress Lottie Gee, is trying to goose a new song, “I’m Just Wild About Harry,” with a propulsive beat. Her inspiration? The construction in the dreary hall where the all-black company is rehearsing. Gee starts beating out a percussive syncopation as a young chorus dancer thrillingly taps out the complex and subdivided counts.

What you hear is the sound of something being born that never existed before, says choreographer Savion Glover, who joined forces with director-librettist George C. Wolfe to reclaim a revolutionary show from obscurity with stars McDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell, Brandon Victor Dixon, Joshua Henry and Billy Porter.

Their show, whose full title is “Shuffle Along, or, the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed,” tells the story of the first production to feature an all-black creative team and to play to mixed audiences during its smash Broadway run in 1921. Wolfe and Glover had teamed up in 1996 for “Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk,” the hip-hop and rap musical revue retracing black history, which won Glover a Tony Award for his wildly innovative choreography.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

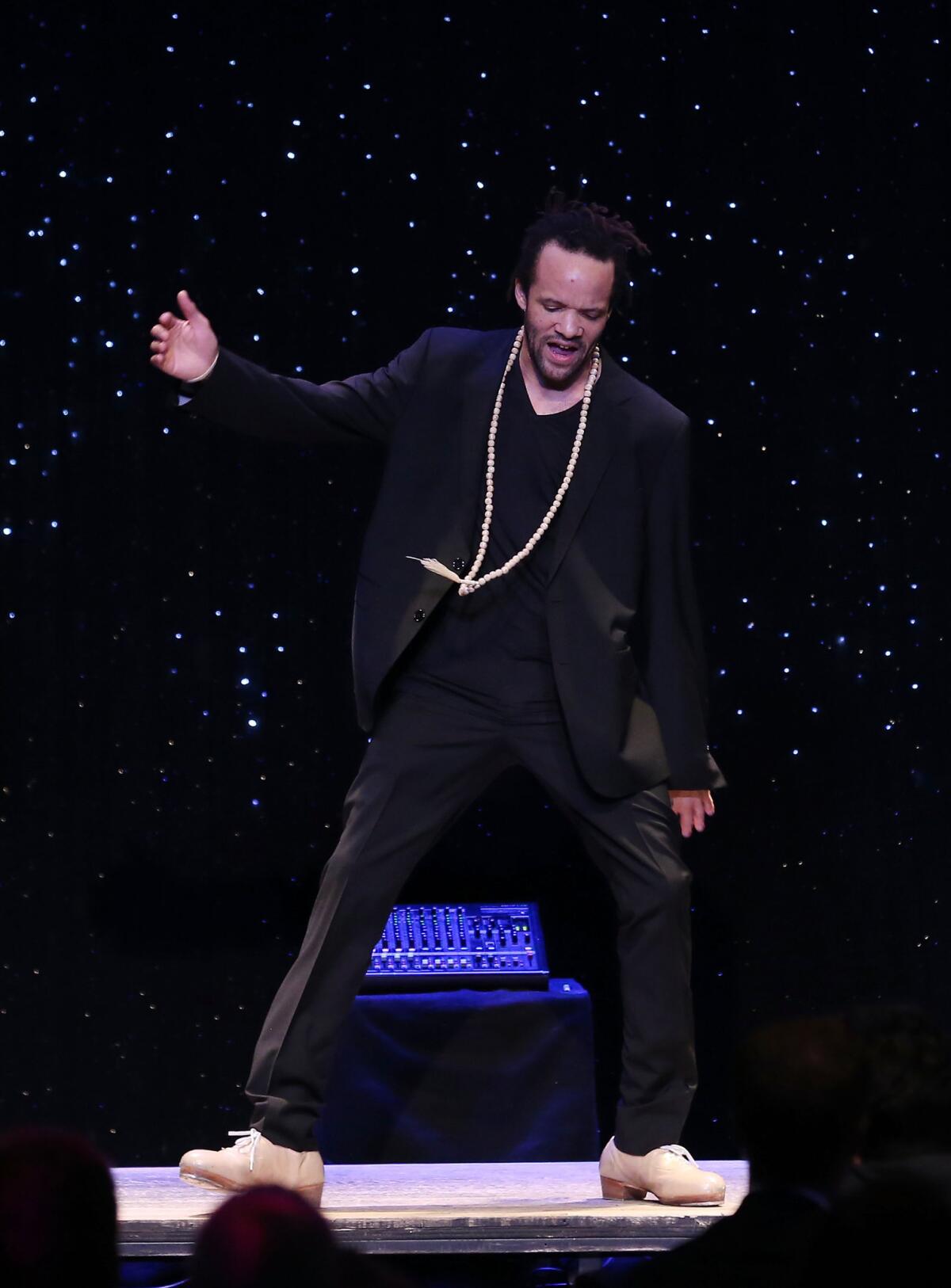

He is up for the same Tony for “Shuffle Along,” which earned 10 nominations earlier this month, including one for best musical. Sitting in the lobby of the Music Box Theatre in New York, where “Shuffle Along” is in residence, Glover, 42, humbly spoke of being the anointed heir of a tap dance tradition and discussed the “cosmic consciousness” that will dominate when he performs in concert with Jack DeJohnette on May 26 at the Valley Performing Arts Center in Northridge.

In tap rehearsals for “Shuffle Along,” Audra McDonald, Brian Stokes Mitchell and Brandon Victor Dixon were really sweating out your routines. No mercy?

Not only was I excited to teach them, but they were enthusiastic about wanting to do it. I always used to say, “Things can be simplified.” But they didn’t want the simplified version. They pushed and pushed and pushed. As a tap dancer, I appreciated that. As a choreographer, my level of respect for them grew and grew and grew.

What was key in the rehearsal room?

You gotta listen; you gotta try to feel it out. It’s not something that you “perform.” It’s something that you have to really think about in terms of its interpretation. I could give them the vocabulary, but the interpretation is theirs.

How did you feel about the denigrating role of blackface in the original 1920s musical around which the new “Shuffle Along” is built?

I had images in my mind that I had to pull from in order to deliver the look of some of the numbers that were of the blackface era. It wasn’t anything that I shied away from. I’ve done productions before that led me to confront the whole minstrel era. It was not anything new to me or my vocabulary.

Black sexuality had been such a threat. The original “Shuffle Along” was the first show to demonstrate romance between two black characters. How did you choreograph that bold statement?

With an extreme level of sensitivity. And something that would be totally nonthreatening would be a soft-shoe.

How did you look upon the challenges that these African American pioneers had in expressing themselves?

That’s what we all want to do, express ourselves, but some of us are contradicted and misunderstood. I wouldn’t say that we want to be understood. Like them, we just want to be. Unfortunately, you still have to prove yourself. You want to believe that the notion of being considered “less than” has passed us, but it has not. You can either go at it with aggression or with love. Hopefully with love.

How did you come up with the number that expresses the rivalry that developed after the original “Shuffle Along” creative team split in acrimony?

My inspiration for that was just to do a challenge, a battle, to be honest with you. I thought of the old challenges done by individuals and extended that to two groups.

You mean the tap challenges between dancers that were done in clubs in Harlem?

Yeah. You couldn’t leave the Hoofer’s Club without a challenge. Some of these challenges would go on for months until someone was ruled a favorite.

Were you challenged?

Oh, yeah. I’ve been challenged by, um, what I would call a “young buck.” [He laughs.] In my very aggressive years as a young man from Newark, I would have different labels on the bottom of my tap shoes: “Yo Mama” on one, “Killer” on another. I went through a period when you had to be ready to, what we used to call, “cut ’em.” You had to have a cut step so that when you were done with what you were doing, nobody had a chance. There was nothing sweet about it. Some people would actually leave in tears.

Did you ever challenge one of your mentors, like Gregory Hines?

No. That’s the thing. Certain generations don’t know how not to challenge. I came up in a time when you didn’t even look in the direction of certain people. Who would think about challenging Jimmy Slyde? ... That’d be like LeBron James challenging Michael Jordan, or Shaq trying to challenge Kareem-Abdul Jabbar. You just don’t do that.

What were you most eager to learn from your mentors?

More about their lives than about their art. That’s what made my relationships with them so significant. It was father to son, especially when there was no male in [my] house. Dancing was secondary. A lot of lessons were learned at dinner versus the studio.

What lessons?

Respect. Manners. How to live in the world. How to deal with America as a black man in this country. Life lessons which had nothing to do with dance. But ultimately they would because wherever I am in my life is all going to come through my dance.

Where are you now versus where you were?

When I was in my teens, my dance was very aggressive: hard, edgy, just rough. Not really caring about an audience or anything but what was a part of where I was from. When you wake up every day to stolen cars and police sirens, that’s different from Beverly Hills. As I got more mature, my dance became more spiritual. Now I am exploring the realm of cosmic consciousness. I just want to explore the unknown as far as sound and time and a person’s space.

Is that what you intend to do in “An Evening With Savion Glover and Jack DeJohnette” in Northridge?

Definitely. Jack plays drums and piano, and he’s an extraordinary man and musician. I didn’t know it then, but my time with those cats [mentors] was all about exploration. It’s about trying to navigate your way through this realm of cosmic consciousness, and it’s so blissful and joyful. We start the concert, and then it’s two hours later and I think, “Oh, yeah. I guess we can stop now.”

How does that cosmic consciousness play out in your art?

It’s what I learned from all these men — Roy Haynes, McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Slyde, Buster Brown, Gregory Hines. They wanted nothing from the world but peace and love, honor and respect. They were ferocious animals with their instrument. But they were also beautiful lovers with their instrument.

What does the term “hoofer” mean to you?

I’m glad you asked me that. The Hoofers were a group of men. Period. Now, today, the word “hoofer” has become a professional tap dancer. It’s wrong, very wrong. You have kids in Wichita from the Sally Dinkle Tap School calling themselves hoofers, and they have no idea who Lon Chaney is or George Hillman or Buster Brown. I don’t care how many lyrics to John Lennon songs you know, you’re not a Beatle! [Laughs.]

Do you consider yourself a Hoofer?

Because they’ve allowed me to be one. I’m just a tap dancer. “To hoof” just means to travel, to get from one place to another. We all do that.

A poignant aspect of “Shuffle Along” is the desire to save these artists of the past from oblivion.

In everything I do, I can’t help but bring them into the room with me. There were times when I would stop in rehearsal, look to the sky and say, “Give me something.” I’m very appreciative of their contribution and knowing they gave us the gift. They invented it. It didn’t exist before. They created it out of nothing. I love making sure their stories are being told.

Follow The Times' arts team @culturemonster.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.