Review: Getting down to the basics in Peter Brook’s ‘Battlefield’

Peter Brook’s “Battlefield,” which opened at the Wallis on Wednesday for a brief run through Sunday, is itself the ultimate brief run. It is the last word in concentrated compression by theater’s greatest condenser.

“We look for indefinably precise things,” Brook told The Times 30 years ago as he was about to mount his magnum opus, “The Mahabharata,” in Los Angeles. When I saw that nine-hour staging of India’s epic poem, done on a sound stage at Raleigh Studios, it was such a grand event that it helped to redefine the possibilities (very much in the plural) of theater for late 20th-century theater.

Ten years in the making with a huge international cast, along with musicians playing dozens of Asian, Middle Eastern and African instruments, Brook’s “Mahabharata” was equally broad in intent, a representation of humanity in its vastness.

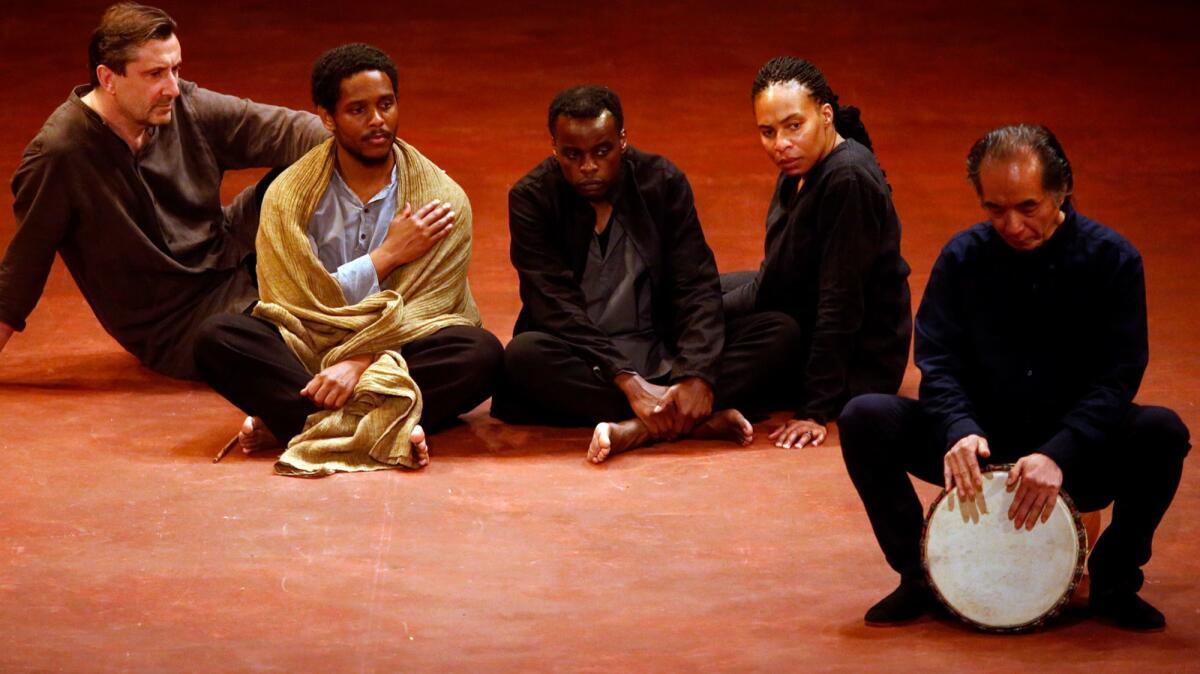

“Battlefield” is a return to “The Mahabharata” on a nearly bare stage, with four actors and a single musician playing a single instrument, a drum. It lasts just over an hour. It is as pure theater as you may ever encounter. Indefinably precise things, indeed. Every syllable here is given the resonance of a note of music. Each word is pronounced as though it encompasses measureless meaning. Each phrase is announced with the scrupulous cadences found in late Stravinsky. No amplification was used or needed.

But “Battlefield” is not what it seems. It is not the final feat in reducing the world’s longest epic poem, eight times the length of the “Iliad” and “Odyssey” combined, into an 18-page script by Jean-Claude Carrière (the original author of Brook’s “Mahabharata”). It is the endgame.

There is no abbreviation. Brook did that when he made a three-part version of his original “Mahabharata” for television (basically the full production without the breaks) and then turned that into a 170-minute wide-screen film. Brook did that when he shortened and reworked Bizet’s “Carmen” and Mozart’s “The Magic Flute.”

While using many of the same techniques found in his pared-down late style, Brook here doesn’t attempt a pocket “Mahabharata.” He instead produces an epilogue that is at once a looking back at his incomparable staging of “The Mahabharata” and an opening for a new beginning.

He steps way, way back and asks what it all means. “Battlefield” ends with: “Now I will tell you what you wish to know.” But Brook leaves us, after an hour that seems neither short nor long but outside of time, knowing nothing. And knowing that you know nothing, you can begin to understand.

The adaptation and staging by Brook and his longtime co-director Marie-Hélène Estienne looks like most of Brook’s recent work. The stage is ritualized space, decorated with a few poles. Oria Puppo’s costumes are robes representing no particular style or nationality. Colored scarves help to identify the many different characters played by exceptional actors who can change personage on a dime.

“The Mahabharata” is the tale (and hundreds of sub-tales) of the war between the 100 sons of the blind king Dritarashtra and the five of his brother. Every effort is made to avoid the war. The gods give inscrutable good advice. But destiny cannot be avoided. The epic bloodshed ends with brother killing brother, cousin killing cousin and hundreds of thousands dead.

All this has already played out when “Battlefield” opens with the victorious Yudishtira looking over it all in horror and unable to face the consequences of his actions. His only desire is to leave the world and become a hermit in the woods. “Battlefield” is the instruction by Dritarashtra, by Yudishtira’s mother, by the gods and others, through example and parable about the ethics of responsibility, of following one’s destiny and trying to make the best of it.

Life is the quest for the speck of vision that comes with death. Maybe — there are no guarantees — the next life will be a little better. The cyclic nature of all things dismisses the possibility of avoidance but not the possibility that by contemplating the larger scheme of things you can start to make sense of the moment.

Karen Aldridge, Jared McNeill, Ery Nzaramba and Sean O’Callaghan play such roles, be they king or hunter, god or a snake, Death or Time. These are actors from different parts of the world, speaking English with a different accent. Yet they share the ability to create the atmosphere of a timeless religious pageant while at the same paradoxical time give the impression that each one is focusing directly on you in the audience.

One more paradox is that they are also listeners as much as actors or characters or seers. They find their cadences through Toshi Tsuchitori’s drum, even when he is silent. The play ends with the cast all silent in intent concentration on a miraculous improvised solo from Tsuchitori (who created the music for Brook’s original “Mahabharata”).

Once Tsuchitori ends, they continue to listen to the silence, welcoming the audience back to its world. That is the kernel of “Battlefield.” This is Brook’s lesson in listening as conduit to second sight.

War may be inevitable, “Battlefield” implies, but it is also the result of stupidity, the handiwork of people who cannot shut up long enough to hear what is being said by the brother or cousin (Sunni or Shiite, Israeli or Palestinian, North Korean or South, Republican or Democrat) whom you believe it is your destiny to defeat.

As an exercise in how to stop and listen to the stories, listen to the environment, listen to death as a way to learn to live, “Battlefield” is meant to stop no battles. It merely points you just a little closer to the right direction, which makes it an essential hour of theater.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Battlefield’

Where: Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills

When: 8 p.m. Thursday and Friday, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday

Tickets: $35-$75 (subject to change)

Info: (310) 746-4000 or www.thewallis.org

Running time: 1 hour, 5 minutes

ALSO

The new LACMA: Plans call for radical change to how we see the permanent collection

Marciano art: New museum proves the potential and the pitfalls of a vanity project

Marciano architecture: Temple loses some of its eccentric personality in stylish redesign

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.