Foster the People mural paints a picture of city’s policy adjustment

Indie pop band Foster the People’s “Supermodel” mural in downtown L.A. generated superbuzz last week when it was set to be whitewashed, according to the band, which cited conflicts with city officials over the mural’s approval. The online fan petition that ensued garnered more than 12,000 signatures, and Mayor Eric Garcetti eventually stepped in “to cool things off,” his office said, postponing the artwork’s removal.

But lost in all the celebratory fan and band tweets was the fact that the mural’s fate still hangs in the balance: Ultimately the owner of the Santa Fe Lofts will decide to remove the mural or will pay to have it retroactively registered with the city and apply to have it cleared by L.A.’s Cultural Heritage Commission.

The even larger issue, however, is how murals are being produced — or not — since October, when L.A. lifted a decade-long ban on public murals. Though the change marked a new era for artists in a city with a deep tradition of murals as chronicles of urban life, those newfound freedoms have come with complications and a process that has been more convoluted than some expected.

Since the mural ordinance passed, only three new murals have been registered with the city: a clean-energy-themed work by artist Kristy Sandoval at the Pacoima Community Center and a project called “Modern Portraiture,” composed of two adjacent murals on the same Hollywood building on Cahuenga Boulevard, created by nine artists and put up by 72U.org, the community service arm of the ad agency 72andSunny.

Sixteen applications for new murals are pending. Eight applications have either expired or were denied. Perhaps most distressing for artists and advocates of public art, however: Three murals have been painted over after problems that have included improper registration. A work by New York artist Ron English, “Urban Bigfoot” on Imperial and Jesse streets in the arts district, was removed earlier this month; a mural by artists RISK and Shepard Fairey, “Peace and Justice” on 6th and Central in the skid row area, was painted over this spring, as was an untitled mural by L.A. artist David Choe and Barcelona-based artist Aryz. That last piece, on 7th and Mateo streets, could have been grandfathered in as a vintage mural if only the building owner had filled out the paperwork, but it was removed on May 5.

The Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs’ new general manager, Danielle Brazell, took her post on Monday morning, and in her first interview on the job she said that addressing concerns over the mural application and registration process among all stakeholders involved — artists, property owners and city officials — was a “top priority.”

“Murals in L.A. are such an important, vital art form,” she said. “We have the ordinance; now we have to have an inclusive process based in transparent criteria in which we can move the murals, get them up and restored.”

As to why so few new murals have been registered since the ordinance passed, Brazell added: “None of this infrastructure was built.... It was about 10 years that we had a broken system. Developing a public process takes time.”

Some say the dearth of new murals speaks to an unnecessarily confusing and lengthy registration process.

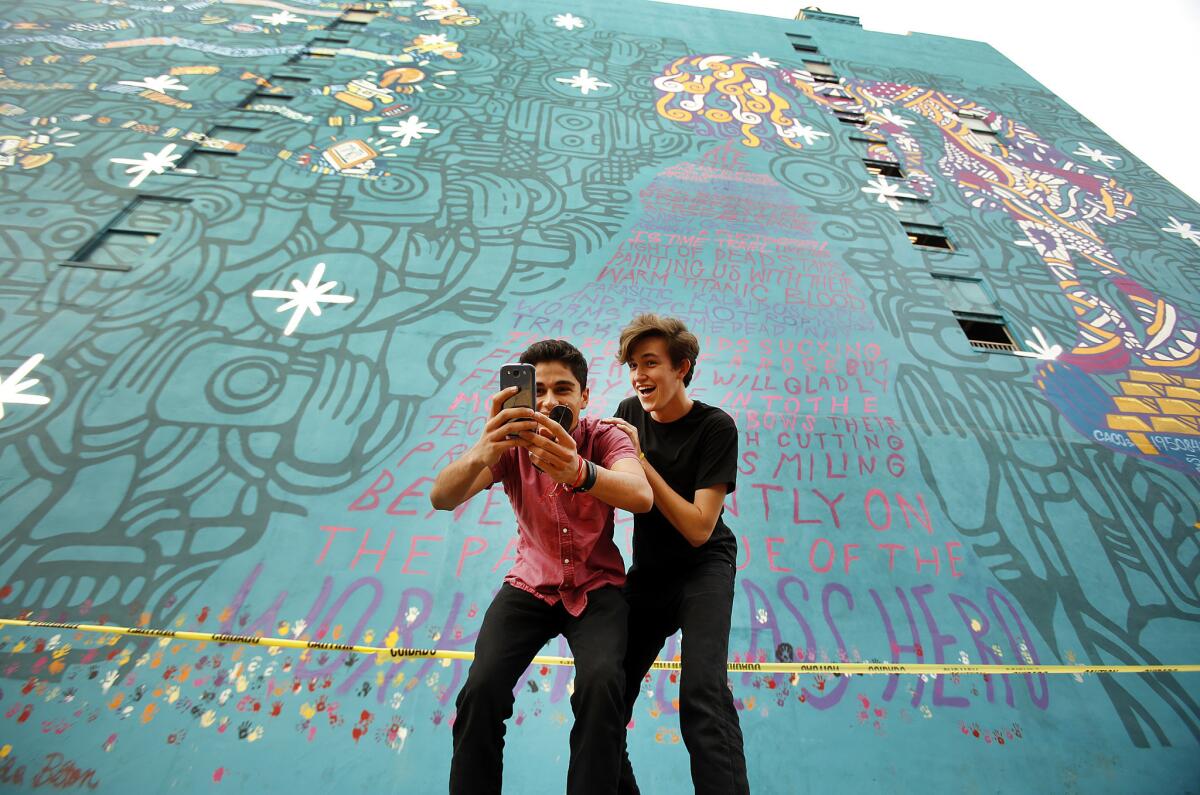

The Foster the People mural was coordinated by Daniel Lahoda of the public art project LA Freewalls, designed by artist Young & Sick and painted onto the building at 539 S. Los Angeles St. by artists Vyal Reyes and Abel Leba. The 125-by-150-foot painting is larger than allowed, and it’s on a building that is an L.A. Historic-Cultural Monument with aesthetic limitations on it. Questions also arose about whether or not the mural — the likeness of which appears on the cover of the band’s “Supermodel” album — was art or a commercial advertisement.

Lahoda said he had initiated the mural’s application process, received a receipt from the Cultural Affairs department and got oral approval to go forward with the painting. The city’s non-compliance concerns, he said, were presented to him only after the mural had gone up.

“In my opinion, this is very much an issue of the city learning to fulfill their policy properly,” he said.

The city, however, said it never officially approved the Foster the People mural — that the application process for the artwork was never completed. “A notice to proceed with fabrication of the mural was not issued,” Cultural Affairs representative Will Caperton said in an email. He added: “Prior to applying for registration, the applicant needed to obtain a project clearance from the Cultural Heritage Commission because the mural is on a city of Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument.”

The incident speaks to the need for further clarity, some say. The day the mural ordinance passed, the city posted it on its website. The nonprofit Pacoima Beautiful, which produced the clean energy mural, has said it had a relatively easy time getting its artwork up. Still, some artists find all the legalities and contracts daunting and prefer to have mural coordinators, such as Lahoda, navigate the process for them.

“I don’t think I understood the particulars of [the mural ordinance] — I had the vaguest notion of all that,” English said of his “Urban Bigfoot” mural. The artist doesn’t hold any grudges over its removal, however. “It got painted over,” he said. “I’m not upset. Part of the fun of all this is that they change out. That’s how street art goes.”

These are uncomfortable but necessary growing pains, said Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles Executive Director Isabel Rojas-Williams.

“The mural ordinance is new to us — and we’re new to it because for 11 years we weren’t allowed to paint,” she said. “So it’s an educational issue we need to work out as a community. If people are claiming they didn’t understand the process, this is an opportunity, going forward, to educate so no one can claim ignorance.”

Rojas-Williams also said the mural registration process needs to be streamlined to encourage people to apply for permits. The final stage of mural registration is obtaining a covenant, a document signed by both the building owner and the person registering the mural, together in front of a notary. “That can be difficult,” she said. “Building owners may be busy or out of the country, and to have the two parties together is hard. We made a list of things that are difficult and how can we make them more fluid so people will be inspired to register their mural. We need to make that last part easier.”

The city is redesigning its website with more updated information about the ordinance and the application and registration process, said Vicki Curry, a representative from the mayor’s office. It also plans to raise education efforts through social media and in-person community meetings, Curry said.

Brazell said that’s all key toward re-establishing Los Angeles as a global mural capital.

“It’s a tremendous opportunity to educate the public, artists and property owners and get feedback on the best way to streamline the process,” Brazell said. “And we need other members of the city family to understand the process,” Brazell said, “and any way we can help streamline that, we will. That’s the work ahead.”

Twitter: @debvankin

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.