Critic’s Notebook: How the L.A. Phil centennial season delivered on the promise of unprecedented goods

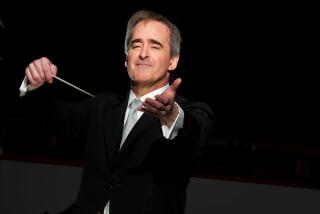

The Los Angeles Philharmonic’s 100th season began late September with good vibrations and radiant light. In Walt Disney Concert Hall, a gala with Gustavo Dudamel conducting the orchestra and Los Angeles Master Chorale along with Coldplay frontman Chris Martin and Doors drummer John Densmore ended in the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations.” The audience sang along.

Outside, projections on the exterior steel of the hall, as architect Frank Gehry always intended, and a spectacular light show made the whole building look like a vibrating L.A. Phil mothership.

When the audacious centennial celebration ended earlier this month, the L.A. Phil was still extracting good vibrations and radiant light from a seemingly inexhaustible reservoir. The spectacle this time was Yuval Sharon’s staging of Meredith Monk’s neglected “Atlas,” which featured a gigantic, spherical mothership, illuminated with startling projections on the Disney stage. Then, in the opera’s final section, “Invisible Light,” magical, otherworldly vocal vibrations powered an out-of-body experience.

History has unquestionably been made. But are these good vibrations that will simply die away, or did they produce tremors strong enough to trigger an arts earthquake, shaking up not just the music world but all sorts of arts institutions and even society? Will we look back upon this unprecedented season as an unsustainable extravagance? Was the radiance too bright? And just how good were these vibrations, anyway?

Merely recounting the massive season is tiring typing. For any other orchestra, performing Messiaen’s gargantuan “Turangalila” Symphony, which principal guest conductor Susanna Mälkki led magnificently, is maybe a once-in-a-decade treat. If you get Mahler’s much more massive “Symphony of a Thousand,” which Dudamel turned into a gripping spiritual experience, once every couple of decades, count yourself lucky.

LA Phil at 100: How the orchestra rose from humble roots to become one of the world’s best »

These, though, were but tips of a centennial iceberg that included ballet (Benjamin Millepied’s shrewd site-specific “Romeo and Juliet”), notable American opera restoration (John Cage’s “Europeras 1 & 2” as well as “Atlas”) and theater (Shakespeare’s “Tempest” with Sibelius’ incidental music). The three B’s got their big-time due, with impressive surveys of Bach’s keyboard music (from organist Cameron Carpenter and pianists Vikingur Ólafsson and Pierre-Laurent Aimard), Beethoven (Dudamel’s survey of the five piano concertos with different soloists and the seldom heard C-Major Mass) and Brahms (conductor emeritus Zubin Mehta’s searching symphony and concerto cycle). So too did Stravinsky in conductor laureate Esa-Pekka Salonen’s vibrant survey, much of it of works from the composer’s L.A. years.

Then there were all those commissions for new works. An astonishing 54 had been announced. For the L.A. Phil, commissioning has become an addiction; by my reckoning, there wound up being 64! The sources ranged from teenage students in the orchestra’s National Composers Intensive to the American octogenarian greats Philip Glass and Steve Reich. There were pieces for guest soloists and ensembles. Tan Dun offered a magnificent, evening-long “Buddha Passion.”

No one could hear them all. The orchestra’s annual “Noon to Midnight” marathon of new music included the last two dozen commissions, and many were played at the same time in different places in and around Disney. That day alone could have been the centennial celebration.

But one 12-hour Saturday was not enough for this institution. The week before, as part of the L.A. Phil’s ongoing Fluxus festival in partnership with the Getty — including the making of a giant salad on the Disney stage and an enlightening tribute concert to Yoko Ono — REDCAT was turned into a cocoon of redemption with Ragnar Kjartansson’s “Bliss.” This time from noon to midnight, three minutes of forgiveness in the finale of Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” was staged repeatedly in a nonstop loop.

TIMELINE: The Los Angeles Philharmonic through the years »

What else? A parade from Disney Hall to Hollywood followed by a free concert with Dudamel and the L.A. Phil in the Hollywood Bowl. Dudamel’s loving and surprisingly illuminating tribute to John Williams’ film scores, which has been released as a glorious recording. Michael Tilson Thomas’ life-affirming performance of Ives’ “Holidays” Symphony. Herbie Hancock’s ear-opening advocacy of a new generation of progressive jazz musicians (yet more commissions). The return of a newly mature and luminous Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla and her program that included the L.A. debut of violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja in a revelatory reinterpretation for our time of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto. A worthy revival of the underrated L.A. African African composer William Grant Still. An installation piece by Janet Cardiff providing a whole new glimpse of Disney Hall. (It remains on offer to visitors most afternoons for the next five years.)

A common response is that the only way for all of this (plus everything I’ve left out) to be possible, the L.A. Phil must be an orchestra inevitably putting vainglorious quantity over quality. For some commentators from afar, such empty L.A. flash is paid for by selling out with soul-sapping, money-making pop concerts at the Hollywood Bowl. The L.A. Phil, this conventional wisdom goes, plays all that new stuff because it can’t compete in the classics.

And then there is the alarm over the richest orchestra in America and maybe anywhere monopolizing the local music scene. Do we need to break up the L.A. Phil?

I didn’t make an exact count, but I attended well over 50 L.A. Phil programs this season, and, yes, the orchestra did pull it off. There were downers. The theatrical elements in “The Tempest” didn’t work. Moby used his opportunity to perform with Dudamel and the orchestra by insulting the audience. But these kinds of things were few and far between.

For one thing, the orchestra not only demonstrated a sense of adventure, unbelievable versatility and a good nature, but also played to the highest standards. In Amsterdam in March, I happened to hear the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, revered for its Mahler, play the composer’s Seventh Symphony under the New York Philharmonic’s Jaap van Zweden. That performance had none of the intensity, depth or orchestral character of Dudamel’s Mahler Eighth.

This is nothing new. Deutsche Grammophon has released a 32-CD and three-DVD centennial set, a selection of the label’s L.A. Phil recordings over the years, along with a couple of discs of historic material. It covers all the music directors from Otto Klemperer in the 1930s to the present. There are many amazingly fresh performances, wonderfully played. Particularly striking is just how good some of Mehta’s old recordings sound.

Of the commissions I heard, several were substantial works, all but assured to become additions to the repertory over time. Andrew Norman’s breathtaking, sense-altering “Sustain” is a landmark in the development of an exciting L.A. composer. Glass’ large-scale Symphony No. 12 (“Lodger”), which featured singer Angélique Kidjo, is a major work. Tan Dun’s passion needs a recording pronto, as do a great deal more of the commissions (fortunately DG was around a lot this season). Thomas Adès’ luscious new ballet score, “Inferno,” is a knockout. (The orchestra will repeat it with choreography in Dorothy Chandler Pavilion next month.)

I was out of town for John Adams’ piano concerto, “Must the Devil Have All the Good Tunes,” written for Yuja Wang. I had to catch up with it recently on the KUSC broadcast of the concert. It may have gotten lukewarm reviews, but I can’t take my ears off of it. Write down, right now, the name of two young composers I discovered during the season: Ann Cleare and Gabriella Smith.

There are lessons to be learned from this centennial blowout. One is that you really can think big if you have enough nerve, enough ideas and the goods to deliver. A $500-million fundraising campaign to foot the centennial bill and more has already reached 80% of its goal. This is the kind of thing donors line up to be part of, particularly when it includes the kind of outreach for which the L.A. Phil is noted — educational programs, ticket giveaways and free or low-priced concerts.

Another is that the centennial represents years of building audiences by making music new and relevant and gripping. Do that and the world can’t but notice. Just look at some of this summer’s most notable festivals in Europe.

Dudamel and the L.A. Phil open the Edinburgh International Festival. The director Peter Sellars has played a key role in the L.A. artistic vision since he was appointed as an advisor to the L.A. Phil in 1992, the year Salonen became music director. This year, his L.A. Master Chorale production of “Lagrime di San Pietro” opens the Salzburg Festival. In addition, Sellars will give the Salzburg keynote speech and direct the festival’s highly anticipated new production of Mozart’s “Idomeneo.”

The highlight of the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence promises to be Salonen presiding over a new Ivo van Hove production of Kurt Weill’s “Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.” Meanwhile, Sharon, who completed his three-year tenure as L.A. Phil artist collaborator with “Atlas,” will revive and revise his Bayreuth Festival production of “Lohengrin,” which opened the exclusive Wagner festival last summer.

The final lesson: Follow the wisdom of Brian Wilson when it comes to “pickin’ up good vibrations.”

REVIEW: Long Beach Opera’s ‘The Central Park Five’ goes where Netflix doesn’t dare »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.