Review: In ‘The Renaissance Nude,’ bare skin speaks with startling eloquence

Six centuries ago, in a side chapel of an important church in Florence, Italy, a wealthy local silk merchant commissioned the artist Masaccio (1401-1427) to paint a fresco of Adam and Eve being expelled from Paradise by God.

The painting rocked the city.

The young artist, then barely into his 20s, chose to break a medieval mold. Showing both figures stark naked, he painted Adam with hunched shoulders and covering his face in profound shame, while Eve tosses back her head, a cry emanating from her crumpled face.

Adam’s fully exposed body, its musculature and genitals described in anatomical detail, stands in sharp but revealing contrast to his wholly hidden countenance. In a reversal, wailing Eve thrusts one hand over her breasts and the other across her groin in a determined (if futile) attempt to conceal her nakedness. The fact of their nudity speaks with startling eloquence.

Bare skin is active rather than passive in Masaccio’s brilliant fresco — not merely a docile detail of a person’s life, but an expressive, potentially weighty element of human experience. At the dawn of the Renaissance in Europe — including France, Germany and the Netherlands as well as Italy — unclothed human bodies are emerging from a long, medieval artistic slumber. They take on new and varied purposes — a remarkable flowering that is the subject of an extraordinary exhibition recently opened at the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Masaccio’s expulsion is not included in “The Renaissance Nude,” of course, frescoes being embedded in plastered walls and immovable. Nor is Jan van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece, a monumental landmark, its despondent, achingly naturalistic Adam and Eve virtually contemporaneous with Masaccio’s duo.

And — no surprise — you won’t find Michelangelo’s breathtaking marble carving, 80 years later, of biblical David, a naked statue whose fame is evidence enough of the central role nudity would occupy by the 16th century in Europe. Some art just cannot be lent — no way, no how.

Strangely, though, such absences help rather than hinder this show. The blinding luminescence of household-name masterpieces would cast deep, dark shadows all around.

Yet it is in that cultural shade that the exhibition goes searching for provocative answers to how, why and to what ends nude figures — female and male — emerged as a major artistic device. I’m not aware of another major museum exhibition that has ever examined this fascinating and crucial subject, even though it has long been staring us in the face.

None of which is to say that exceptional loans have not been secured by the show’s organizers — Thomas Kren, Getty manuscript curator emeritus, and scholars Jill Burke, Stephen J. Campbell, Andrea Herrera and Thomas DePasquale. There are great things to see, mostly from public collections in Paris, Dresden, London, Warsaw, Vienna, Edinburgh, Venice, Florence and more.

Take Titian’s exquisite “Venus Rising From the Sea,” a quiet visual celebration of sensuous tactility.

The goddess of love, sex and fertility has just been born of the ocean waves, the warmth of her ample, fleshy body made all the more voluptuous by the simple action of using both hands to twist her cascade of long, auburn tresses, wringing out the water. The painter’s glazes of soft, glowing color rendered with delicate brushwork make the caressing touch of Titian’s brush against canvas a template for a viewer’s imagination. We witness the goddess’ touch mingling with that of the artist.

Titian’s friend Giorgione manages something similar in “Laura,” one of a bare dozen known pictures by the great Venetian artist.

It’s a waist-length figure of an unidealized young woman, perhaps a courtesan or poetic muse. She has pulled aside her fur-trimmed red mantle to expose one nurturing breast. Giorgione knits together a riveting display of touchy-feely surfaces – fur, velvet, sheer gauze, warm skin and loosened hair, plus the surface of a canvas gently brushed with luscious oil paint.

Finally, he adds a mischievous glint of light to both of the young woman’s eyes. In the face of it, a viewer’s own eyes sparkle.

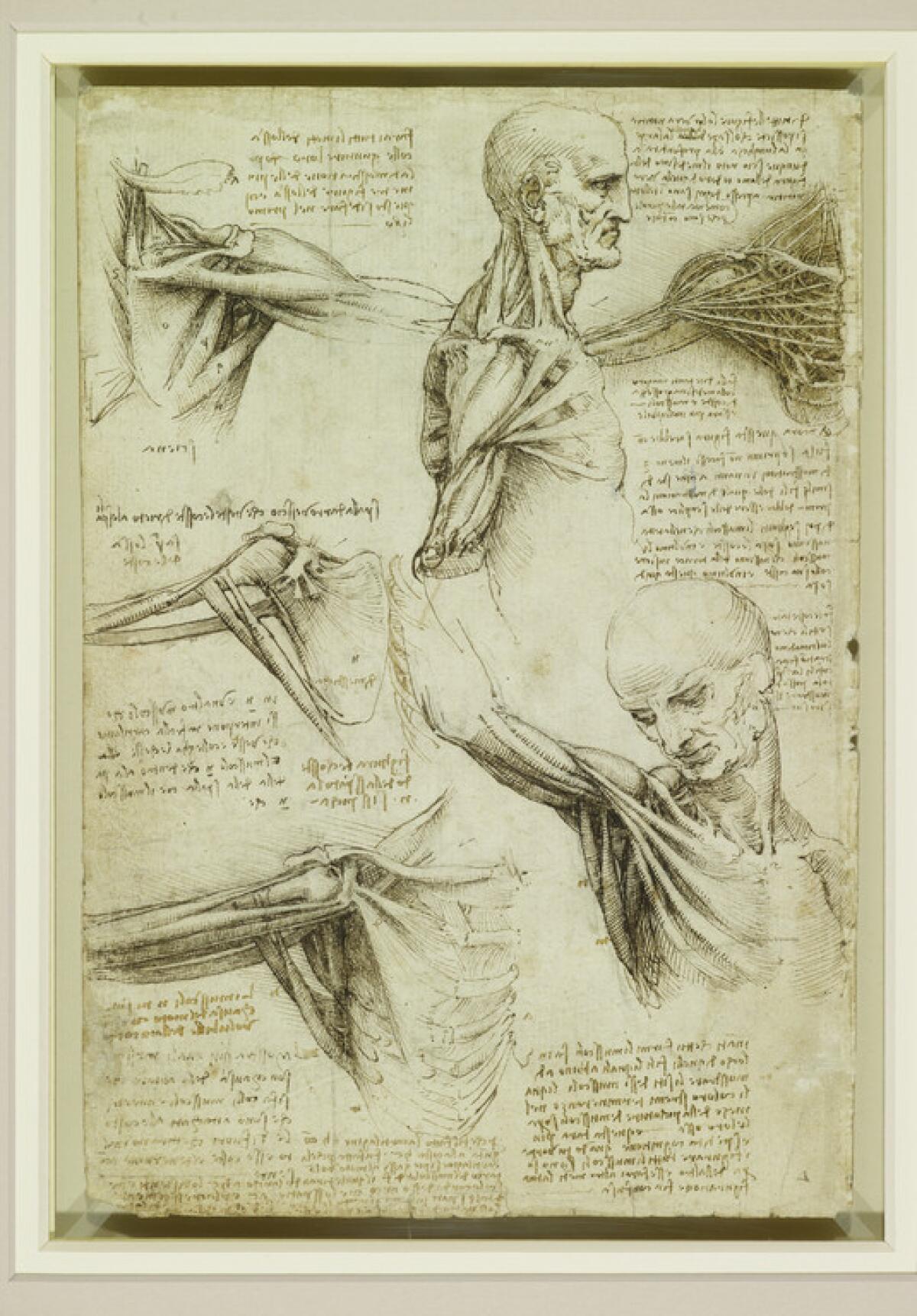

One corner of the show brings together drop-dead drawings by Leonardo da Vinci (a double-sided sheet of 11 anatomical studies in fluid pen and ink with black chalk) and Michelangelo (three red chalk renderings of Hercules’ labors). In both, the male nude occupies center stage.

For Leonardo, the underlying machinery of the male body is humanity’s hidden engine, here revealed in an anatomical striptease that cuts through the outer cloak of skin to reveal muscle, tendon and bone beneath. For Michelangelo, the power and perfection of a hero’s muscular, commanding body are signs of moral strength as much as physical might.

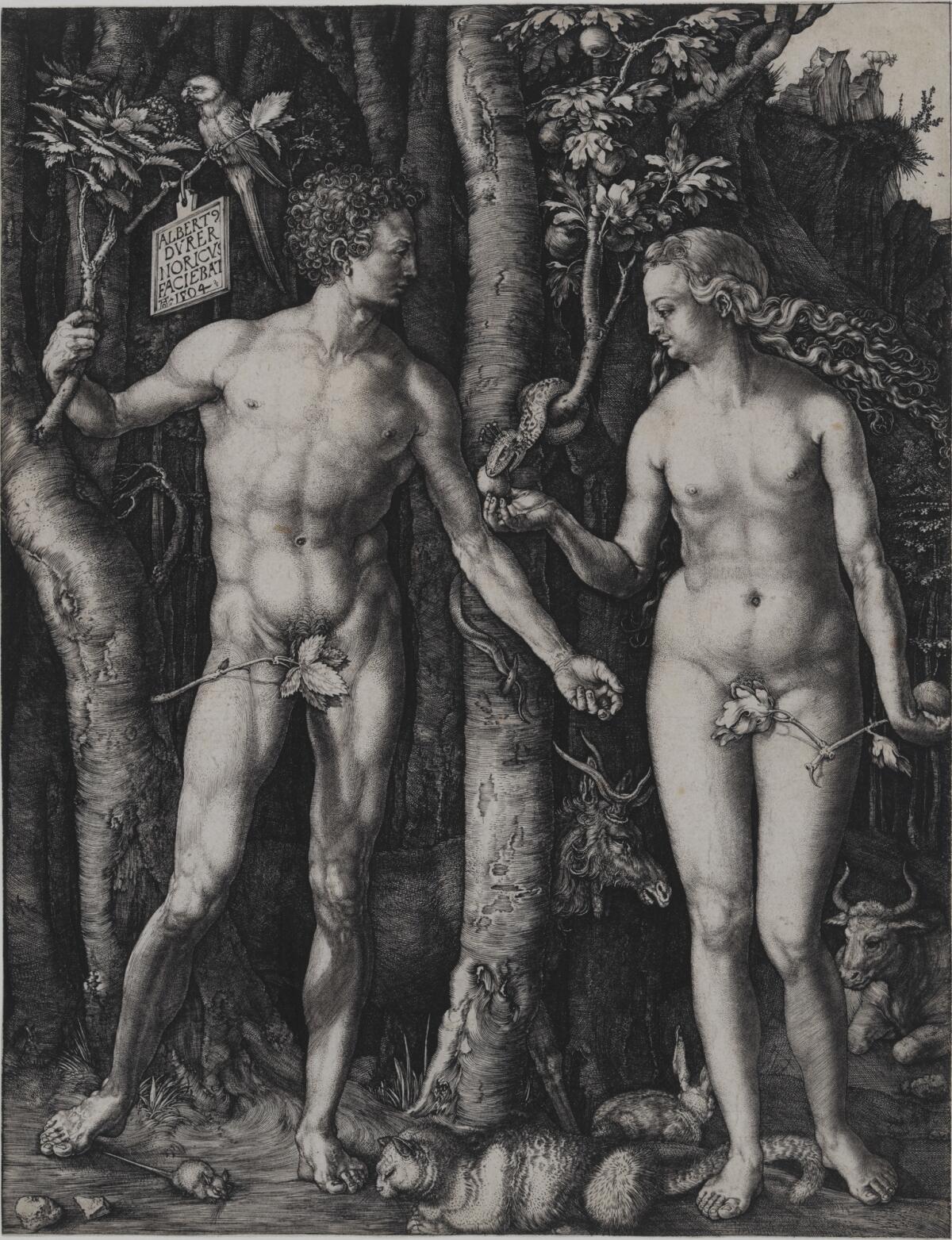

Nearby, a beautiful impression of Albrecht Dürer’s celebrated engraving of Adam and Eve splits the difference between anatomy and moral consequence. In richly modulated black inks, the German genius transforms pagan sculptures of Apollo and Venus into a riveting image of the biblical pair. Crafting ideal bodily proportions, he represents the frozen moment just before Adam and Eve partake of the forbidden fruit, sealing humankind’s fate.

Dürer uses frank but romanticized nakedness to raise the stakes for salvation, pivotal doctrine of the faith. The impossible flawlessness exposed by the nudity of Christianity’s ancestral couple heightens the tension of their fall — and its tragedy.

The show’s wide-ranging material is helpfully organized into six thematic sections. They include the revival of classical humanism from ancient Greece and Rome, as well as nudity as an essential component for the appropriate professional training of painters, sculptors and graphic artists.

But the show opens with the fundamental role of nudity in depictions of a suffering Jesus. That’s unsurprising yet powerful, given a religion predicated on the mystical qualities of the body and the blood.

Even in Christian guise, however, secular eroticism is not neglected. Two popular Renaissance subjects, one Old Testament and the other New, are explored. Lovely Bathsheba, object of King David’s lust, and hunky Saint Sebastian, the soldier’s muscled body pierced with phallic arrows, are represented in a dozen works. Donatello (Italy), Martin Schongauer (Germany), Jean Bourdichon (France) — in geography and artistic temperament, the show travels far and wide.

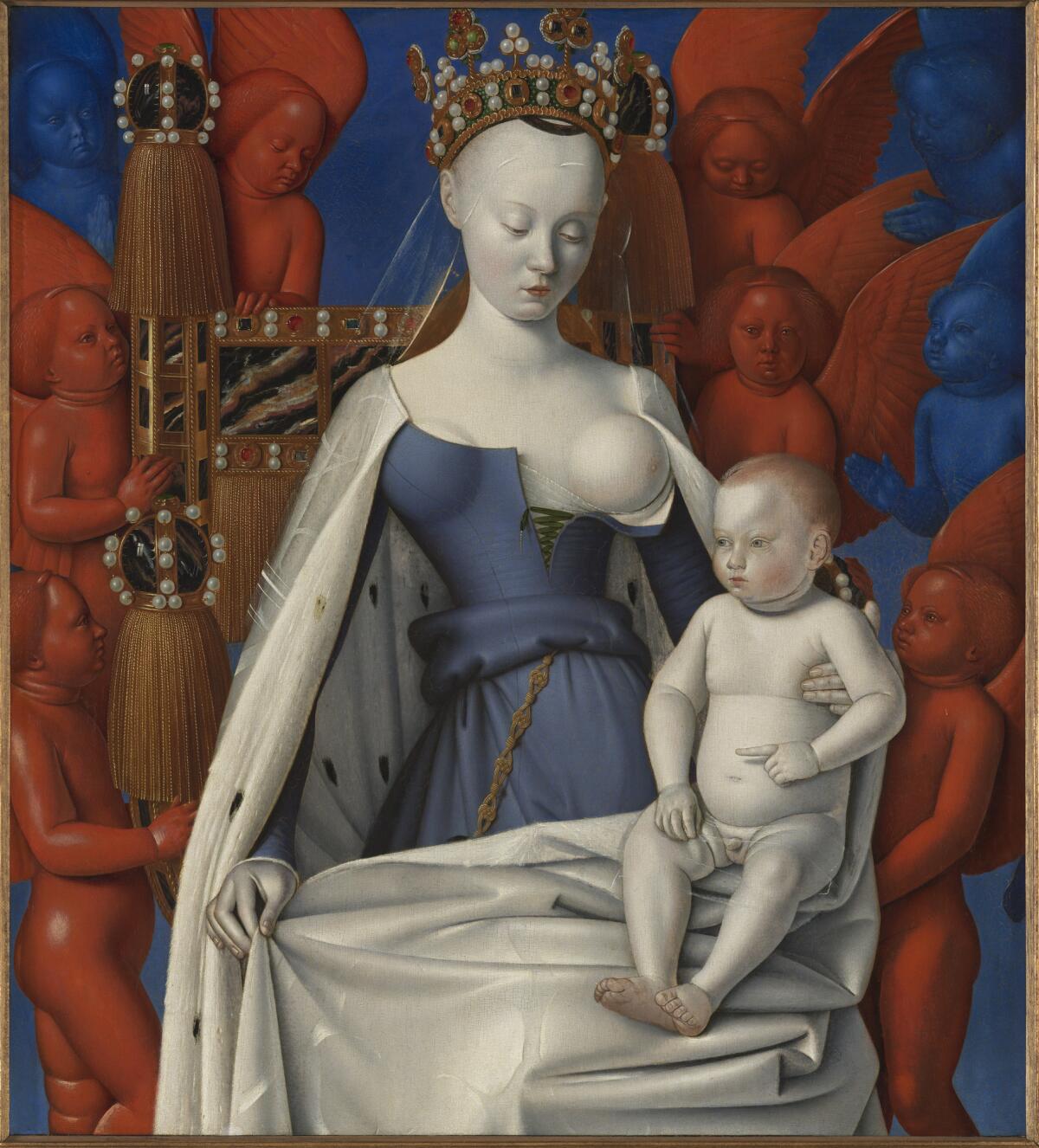

And some works initially come across as just plain weird — gorgeously strange, you might say, at least to modern eyes. At the top of the list is a “Virgin and Child,” circa 1452-55, a large and magnificent panel painting by France’s Jean Fouquet.

Perhaps better known for his exquisite manuscript illuminations, Fouquet was also a favorite painter of Charles VII. Here he cast the delicate porcelain features of Agnès Sorel, a celebrated beauty who was the French king’s mistress, as the radiant Madonna.

Her loosened corset and exposed left breast are surrounded by ermine, satin, golden tassels and a crown of jewels and pearls. She’s attended by half a dozen crimson seraphim and three royal blue cherubim. Fouquet merged the Queen of Heaven with the Monarch of the Boudoir, as if a pre-Freudian Renaissance mashup of Madonna and whore.

Scandalous blasphemy? The show’s terrific catalog explains what might be casually misconstrued as such. Sorel had died in 1450, before the panel was painted. Fouquet’s ravishingly refined image might well be a private memorial intended for an inconsolable king.

More than 100 works are in the show — a slightly different version travels to London’s Royal Academy of Arts in March — and it includes many absorbing works like Fouquet’s. The kicker in the final room is a big surprise — a very peculiar painting by Mannerist master Agnolo Bronzino, which relates Ovid’s story of Pygmalion, the classical sculptor whose passionate love for a comely marble statue of a nude woman brought her to miraculous life.

Bronzino’s panel was made as a cover for Jacopo Pontormo’s magnificent “Portrait of a Halberdier,” one of the greatest treasures in the Getty’s permanent collection. Who knew that Renaissance portrait paintings sometimes came with a protective cover, like a book? This cover, now in the collection of the Uffizi in Florence, is remarkable.

Pontormo captured the handsome, courtly young soldier, perhaps 15 or 16 years old, at a transitional moment between boyhood and manhood. Bronzino suavely framed that decisive evolution behind an ardent story of an artist’s nude brought to full and voluptuous life. Seeing the two paintings side by side for what might be the first time in centuries is not to be missed.

J. Paul Getty Museum,1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood, (310) 440-7300, through Jan. 27. Closed Monday. www.getty.edu

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.