Appreciation: Robert Mann: A musical revolutionary on par with Cage, Bernstein, Callas and Gould

Robert Mann once explained in an interview that, zealously fired up after founding the Juilliard String Quartet in 1946, he went so far as to obtain an orgone accumulator. It wasn’t enough that the feisty young ensemble already exhibited an explosive energy the likes of which had never been imagined in the refined realm of chamber music. The irrepressible violinist expected to further intensify Beethoven and Bartók string quartets with some of that supposed psychic/sexual power (later debunked) from the so-called orgone force.

“My epitaph,” Mann joked to me, “will be that I was the first person to put a string quartet in an orgone box.”

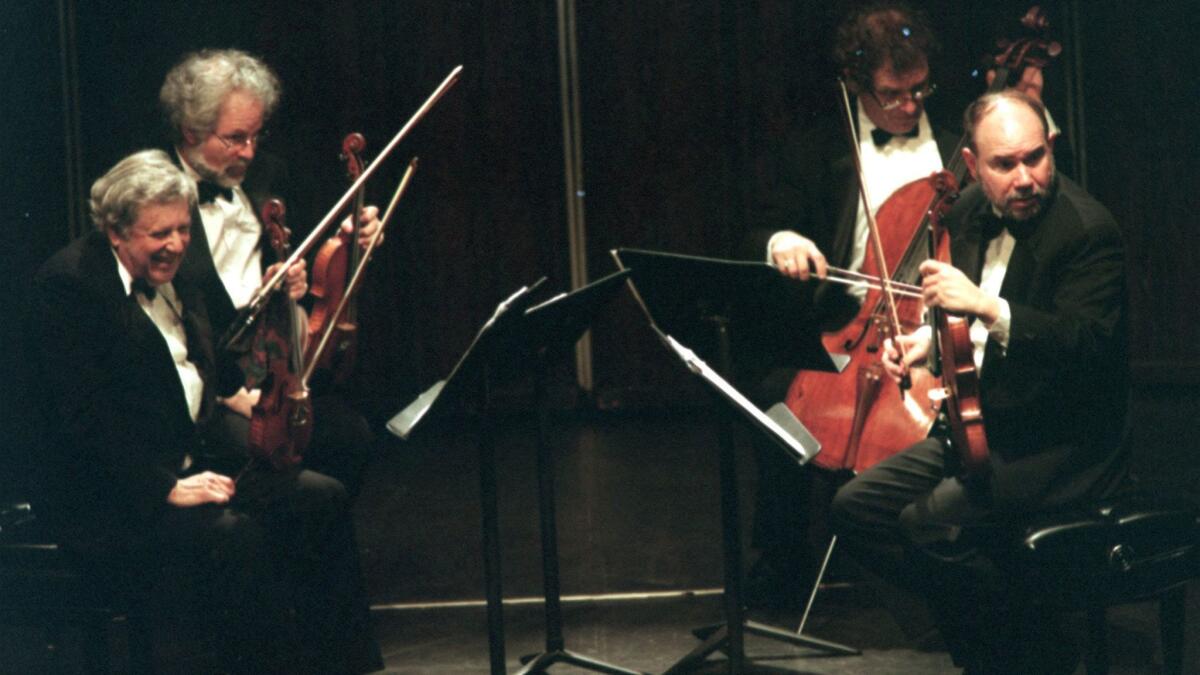

The time, I’m sad to report, has now come for that epitaph. Mann died at age 97 on New Year’s Day. Sorry, Bobby (as everyone called him), the obvious epitaph is that he was the founder, and for 51 years the leader, of the Juilliard String Quartet, which played an incomparable role in the chamber music revival. But that’s not enough even if you, like me, presume the Juilliard under Mann the greatest string quartet of all time.

In fact, Robert Mann was one of a handful of transformative American musicians who in the years after World War II forever changed the way we think about and make music, who gave it a new meaning and a new necessity for a new age. The others were John Cage, Leonard Bernstein (whom you will be hearing plenty about in this, his centenary, year) and Maria Callas (whose music education may have been in Athens, but who was born and grew up in New York). The Canadian Glenn Gould, as a North American, also belongs. As a collaborative chamber music musician, Mann could hardly have become the household name of the others, but he was of their ilk.

What Mann shared with them was the compulsion of immediacy, a dramatic sense of the now that Cage brought to individual sounds, that Callas brought to opera, that Gould brought to everything he touched on and off the keyboard and that Bernstein brought to everything, period. All of them supplied a revolutionary new-world spirit to classical music, putting expression and passion for progress above blandly comforting old-world beauty.

As a young violinist just out of the Army at the end of WWII, Mann approached composer William Schuman, then president of the Juilliard School, about forming a string quartet. Mann’s pitch was: “We will study old music as if it had just been composed yesterday, and we will play new music after studying it as if it had been written a long time ago.” That is precisely what the Juilliard String Quartet magnificently did for the next half century.

Its start was historic. The very first concert — in 1946, the year after Bartók died — included the Hungarian composer’s most aggressively difficult quartet, his Third. Bartók was at the time neglected, his six string quartets little known. Before long, the Juilliard played them as a cycle and recorded them, creating a shocking instant awareness not only that this was one of the great musical legacies of the 20th century but also that these works could provide inspiration for progressive American composers, the likes of Elliott Carter and Milton Babbitt, to reexamine the possibilities of the string quartet as a medium they could themselves exploit.

The Juilliard was right there for them. Carter’s five quartets would ultimately become an essential late 20th-century cycle, and the Juilliard was his favored ensemble. In his 1959 complex Second Quartet, written for the Juilliard, he gave each instrument a distinct personality. If you want a perfect minute-and-a-half portrait of Mann — skittering, propulsive, boisterous, spiritually awestruck, funny, street-smart, self-reliant, challenge-hungry — there is nothing better than the Cadenza for Violin I that comes near the end of Carter’s Second. Living up to that vow to treat new music as if it deserved the care of old masters, the Juilliard was reputed to have spent hours working on a single bar of Carter in rehearsal.

The same was true of the classics, especially Beethoven’s quartets. Beethoven’s “Grosse Fuge” went like a bomb every time the Juilliard played it with a vigor that felt downright dangerous, musical shards flying dangerously throughout the hall. Those shards got more raucous as the years went by and as Mann’s intonation began to slip. It’s not that he never cared about beauty. There are moments in the Beethoven slow movements that are as evocative of the great beyond as the most impressive vistas of nature. It was just that beauty had to be earned the hard way.

That could be traced to Mann’s boyhood in Portland, Ore. His first love was the great outdoors, and he never lost his love of the wilderness. He was a fine violinist, but for him, the emphasis was on the vista — the getting there, the adventure of the climb and the spiritual rewards of contemplating nature.

He was also a complete cosmopolitan, and the contentiousness of city life also went into Mann’s string quartet compulsiveness. He outlived a number of Juilliard members during his 51 years, and he was known not only for his avid outspokenness in rehearsals but also for encouraging outright cockiness in others, leading to the regular fights he relished. If music were to matter, you didn’t hold back.

For Mann’s last several years in the quartet, colleagues and critics regularly advocated that he retire from the group before his intonation became unbearable. He later told me he didn’t understand what everyone was complaining about; his intonation was never all that hot.

He exaggerated, but just a little. Most of today’s string quartets can play Beethoven’s C-Sharp Minor Quartet, Opus 131, with more polish than the Juilliard did in its heyday, on its 1962 recording. If you listen to it now, remastered in high resolution, you may be struck by all the imperfections newly highlighted, but every imperfection is its own spiritual highlight. This is one of a handful of greatest recordings from arguably the greatest string quartet.

In the late years, when I heard the ensemble the most, Mann’s rawness was simply a given. But the performance never came close to losing a physical force gripping enough to make one believe in a musical orgone force that science has yet to discover.

Mann had another two productive post-Juilliard decades teaching, composing and conducting (while the quartet has continued with ever new members). He was a born conductor, often seeming to lead his string quartet performances onstage. That could have easily been his career.

Mainly, though, he leaves the kind of legacy that Cage, Callas, Bernstein and Gould left us — an example of how to proceed. In refashioning the string quartet for a modern age, Mann made it possible for the Kronos to then instigate a second string quartet revolution. Now we have a vital new generation of quartets popping up everywhere, and Bobby Mann’s DNA is somewhere in them all.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.