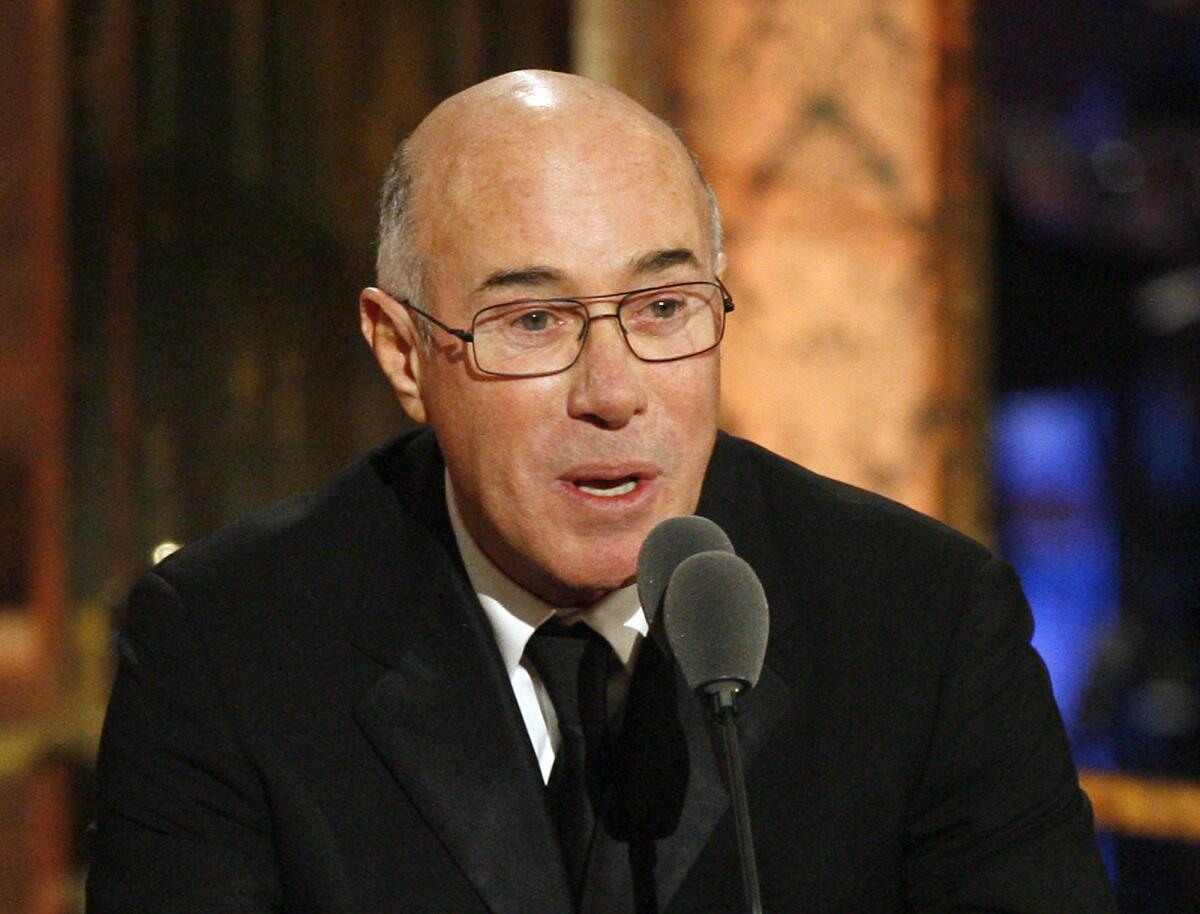

Critic’s Notebook: How David Geffen’s gift to Lincoln Center reflects on Music Center

With the news Wednesday of David Geffen’s $100-million gift to Lincoln Center for the renovation of Avery Fisher Hall — which will be renamed David Geffen Concert Hall — the first sound I thought I heard was a resounding slap in the face of the Music Center.

Isn’t the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion even more in need of an acoustical overhaul? Haven’t naming rights to the Music Center been up for $100-million grabs for nearly a decade? Isn’t this, its 50th anniversary season, the right moment for some Music Center action?

And isn’t Geffen one of L.A.’s most generous philanthropists?

But there is one more question: Did the Music Center even bother to come calling?

Rather than capitalize on the celebration of an institution that changed the profile of the city over the last century and propose an imaginative future, the Music Center is looking desultory. All it has to show so far for the anniversary has been an embarrassingly tacky fund-raising gala in December, farmed out to a Texas corporate-event outfit. The Music Center’s president and chief operating officer stepped down earlier this year. A search goes on. (A Music Center spokesman said it had not yet begun to court donors for renovations.)

Lincoln Center, on the other hand, offers many attractions for Geffen. The place has its problems but it is, nevertheless, an extremely vital campus, bustling with activity over 44 performance spaces, large and small year-round. Although a longtime Angeleno, Geffen is a native New Yorker who maintains an apartment in the city.

He also got a good deal. For some time now, $100 million has seemed to be the going rate for getting your name on a concert hall. Avery Fisher — which has bright, blatant acoustics, lacks intimacy or architectural grace and is plain ugly — will be gutted. The exterior shell will remain, but it will be a new hall inside, one intended to suit the New York Philharmonic, one of the world’s great orchestras.

But $100 million is not a lot for a job that is said to cost more than $500 million. Lincoln Center would do well to consider the Music Center’s experience with building Walt Disney Concert Hall. Lillian Disney gave $50 million in 1987 for what she was led to believe would be the full cost of a new hall for the L.A. Philharmonic.

The orchestra knew the final figure would easily be double, but it figured her contribution would be enough to easily get the fundraising ball rolling. It wasn’t. During the next decade, the new hall almost died more than once. In all, Disney, which opened in 2003, took 16 years to get built and, at $274million, cost nearly six times Mrs. Disney’s gift.

Maybe Lincoln Center will be luckier. Unlike the Music Center, it is more than just a collection of venues and resident companies. It puts on festivals and has vital presenting programs. New Yorkers often say they are going to Lincoln Center, whereas we are more likely to say we are going to Disney Hall or one of the individual Music Center venues. There is no Music Center Festival or anything else. In summer, Disney and the Chandler are dark but for the occasional rental.

The irony of Geffen’s donation, though, is that the one Lincoln Center company that does look to L.A. as a model is the New York Philharmonic. When the L.A. Phil got worldwide attention for hiring a young music director, the New York Philharmonic followed suit. Gustavo Dudamel and Alan Gilbert both began in 2009.

In its struggle to keep up with L.A. in new kinds of projects and new music, the New Yorkers have appointed the L.A. Phil laureate conductor, Esa-Pekka Salonen, as composer in residence for three years. The New York Philharmonic is even hoping to get a little West Coast cred (or at least beach weather) with an ongoing residency beginning this summer at the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara.

Now that the New York Philharmonic has announced that Gilbert won’t continue as music director once his contract expires in 2017, Salonen’s name, along with Dudamel’s, are prominent among conductors sure to be sought after. The likelihood of either accepting seems remote, but so did the likelihood of Geffen spearheading a new Lincoln Center hall.

Ultimately, there is no way for this to look good for the Music Center. LACMA, which is also celebrating its 50th anniversary, is thinking big, using the occasion to generate support for the building of an attention-getting new campus on Wilshire. Were the Music Center to be thinking grand on Grand Avenue, perhaps it might have gotten Geffen to have wanted his name on the center.

One thing, at least, the Music Center will do as part of its 50th anniversary will be to produce a new version of John Adams’ “Available Light,” a collaboration between the composer, architect Frank Gehry and choreographer Lucinda Childs. It is a natural choice given that Adams is the L.A. Phil creative chair and Gehry the Disney’s architect and a member of the orchestra’s board.

But it is an odd choice because the work celebrates a different institution. It was commissioned 31 years ago by MOCA to open what was called the Temporary Contemporary, the exhibition space in Little Tokyo the museum used before its home on Grand was completed, and now used for the museum’s large shows.

“Available Light” is suddenly an ironic choice as well. In 1996, thanks to a $5-million gift from a collector, MOCA renamed Temporary Contemporary the Geffen Contemporary.

Twitter: @markswed

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.