Review: ‘Alternative Dreams: 17th Century Chinese Paintings From the Tsao Collection’ at LACMA

“The way of painting belongs to the one who believes in having the universe in his own hands,” wrote Dong Qichang four centuries ago, “and that before his eyes there is nothing but life and the motivating forces for life.”

Dong should know. The painter led what amounted to a lasting artistic revolution in 17th century China.

A magnificent survey of Dong’s work was shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1992. “The Century of Tung Ch’i-ch’ang, 1555-1636” was a landmark exhibition organized by Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. (The spelling difference in the artist’s name reflects changes in the Romanization of Chinese characters since then.) Now, fine examples of Dong’s paintings start off a large, new LACMA exhibition.

“Alternative Dreams: 17th Century Chinese Paintings From the Tsao Family Collection” features more than 120 works – including an imposing set of 10 calligraphic hanging scrolls by Dong and another that unfolds a mountain landscape through a twisting, turning journey across time and space. The show is a stately, absorbing overview from a tumultuous, invigorating era in art.

It is a decidedly specific overview, however, limited by reliance on the surely impressive holdings of a single private collection. The show is a survey of one collector’s informed tastes. Its subject is the late Bay Area art dealer Jung Ying Tsao.

Tsao was born in Tianjin, China, and trained as a lawyer in Taiwan after escaping the 1949 Chinese Communist revolution. He assembled what is considered by many to be a premier collection of traditional Chinese painting, a project started in the 1950s and accelerating after his 1963 emigration to the United States.

Following his death in 2011 at 87, a long-term loan of the collection’s 17th century material was arranged by prominent LACMA curator Stephen Little, whose relationship with the Tsao family spans four decades. (Little’s first curatorial position was at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum in 1977.) The loaned collection has been the focus of study by visiting scholars and students from Southern California colleges, and the Tsao family’s foundation has underwritten the current exhibition and publication of its massive, nearly 700-page catalog.

In an email, Little confirmed that LACMA hopes to acquire the superlative collection.

That would be a coup – a coherent, brilliantly focused body of work that would also more than double the museum’s holdings in Chinese painting. The snag is that the show and book should typically come after an acquisition, not before.

The show is a demonstration of institutional goodwill in the pursuit of an acquisition; that might sound like a good idea, but rarely does the hoped-for result come to pass. Absent a quid pro quo, vanity exhibitions of private collections attached to names like Simon, Hammer, Gilbert, Smooke and Broad have led to disappointment at LACMA over the years. Color me skeptical.

Tantalizingly, 17th century European painting has been a prime growth area for LACMA’s permanent collection. The Tsao family collection would dramatically extend that reach to the other side of the globe.

The 17th century saw the fall of the Ming dynasty, which ruled first from Nanjing and then Beijing’s Forbidden City for nearly 300 years. Its corruption and decay were swept out by peasant rebellion and Manchu military power.

Dong Qichang, a scholar artist of incomparable gifts, died not long before the 1644 collapse. But his herculean artistic example was picked up by new generations of painters as an emblem of Qing dynasty China’s new direction.

Embracing the veneration of history so prevalent in Chinese art, Dong shifted art’s most esteemed terms. He split what had come before into two groups.

The Northern School included meticulous, often pedantic academic art of the established court. Nature was faithfully described.

By contrast, the Southern School – which included Dong and his circle – espoused the value of individual temperament. Expressive brushwork and skillfully structured composition took center stage.

Understanding nature was still an aesthetic goal, but not as something separate, detached and discrete. Nature is instead conceived as a projection of mind, its human dimensions traced by the artist’s brush.

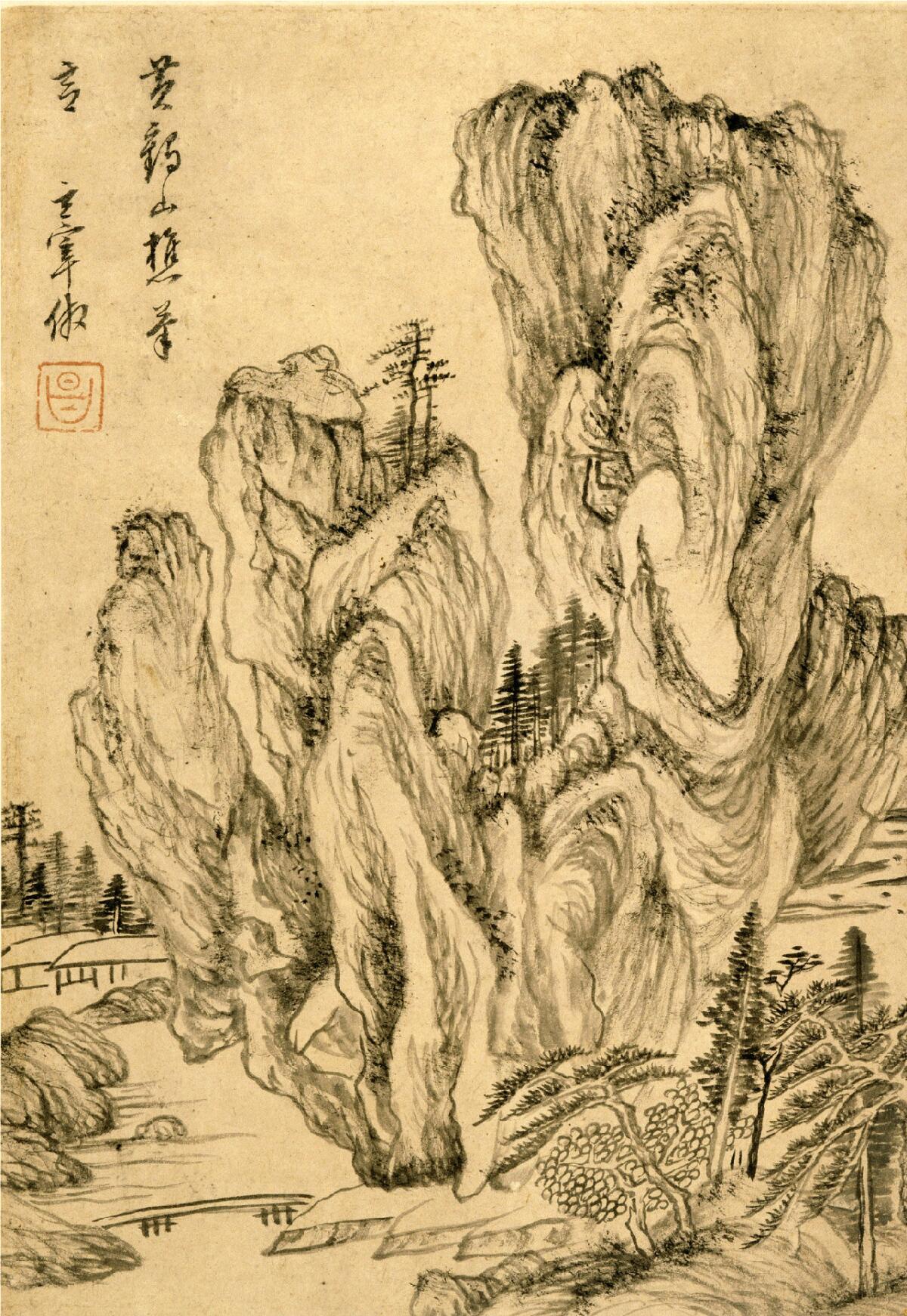

At LACMA, an extraordinary Dong landscape scroll records a visual journey that starts at the bottom from a humble house and winds through a graceful forest, across a river and up into a rocky mountain fissured with waterfalls. The imposing, crystalline mountain is slammed up side by side against a hazy, atmospheric river valley that stretches into the far distance.

Marks of the brush, feathery and staccato, carefully muster tonalities of black ink to create space, depth, linear rhythm and implied motion. Unpainted negative space is as strong and powerful as the painted forms. Solid and void, created simultaneously, are held in vivid equilibrium. The landscape breathes.

Look closely, beyond the forest and at the foot of the mountain, and a second simple house comes into view, raised on stilts over the river. The tiny figure of a man is glimpsed through a window.

He’s doing what we’re doing, contemplating the scene. Slightly above and to the right, another pavilion – this one empty – stands on a promontory silently inviting a viewer’s eye to rest a moment and gaze out over the meandering river below. Then the climb up the mountain begins.

For me, Dong Qichang was China’s Cezanne.

— Christopher Knight

Dong was 73 when he painted this exquisite, 4-foot hanging scroll. It marshals the skill of a lifetime, which the show lays out in a variety of works, all from the second half of his life. There are hand scrolls, individual sheets and a folding fan, some painted in the style of earlier masters, as well as numerous examples of wonderful calligraphy and studies that combine writing and painting.

In a sense, Dong’s paintings and artistic philosophy seem to have anticipated the larger social cataclysm that would soon engulf 17th century China. Rigid, uniform rules for all gave way. Individual consciousness is extolled.

The artist’s quotation above represents his insistence that “having the universe in one’s own hands” is essential for making a work of art. And making art is an exemplar for living.

For me, Dong was China’s Cézanne. It is easy to see why LACMA, which has no paintings by him in its modest collection of traditional Chinese painting, would be eager to acquire the Tsao family collection.

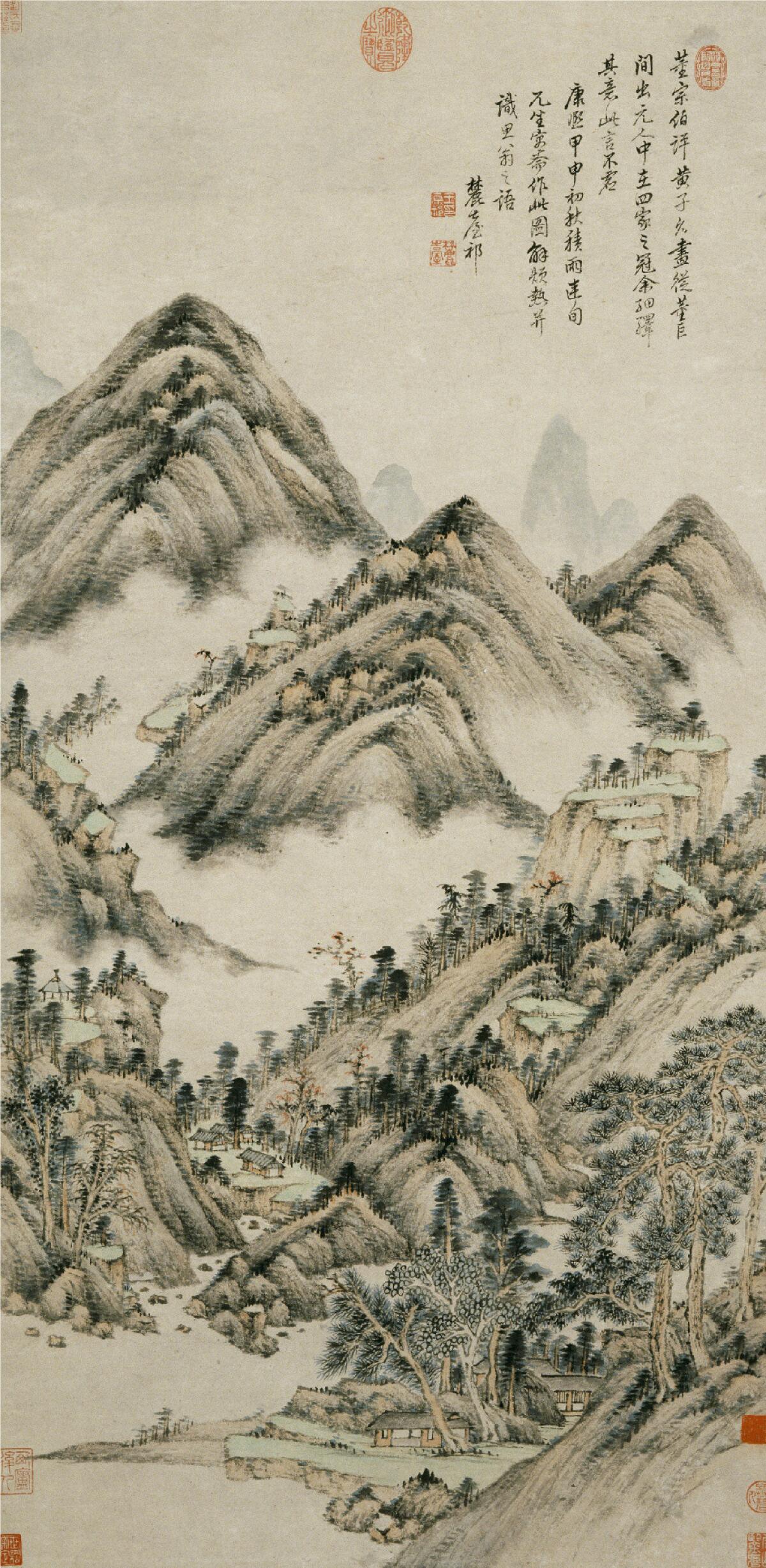

With Dong’s own scholarly acumen as a guide, the collection Tsao assembled also unfolds the widespread influence the artist gained as the Qing dynasty consolidated its power. The work of more than 80 artists is on view in a handsome, minimalist installation designed by Frederick Fisher and Partners Architects.

It’s a demanding show, one that defies casual perusal. But it rewards close looking.

Round a corner and a burst of crimson camellias in the center of a floral scroll by Fang Hengxian is a small, sudden explosion of color in an art elsewhere dominated by shades of black ink. Colorful paintings of flowers and birds gather auspicious symbols for attributes like happiness or longevity. The show’s only women – Ma Shouzhen (an eminent courtesan) and Cai Han – were famous for painting elegant orchids and evergreen pines.

Most Westerners (including this one) are unlikely to have much acquaintance with standard fixtures in the history of Chinese art – the so-called Nine Friends of Painting, for example, a group united more by their mention in a poem than by a shared style; or, the Four Wangs (Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Yuanqi and Wang Hui), who were convinced that they alone were the true guardians of Dong Qichang’s legacy.

So it would be great if the extended loan became a permanent acquisition at a public museum of LACMA’s stature. Whether it will remains to be seen.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

christopher.knight@latimes.com

Twitter: @KnightLAT

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.