Live: Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra

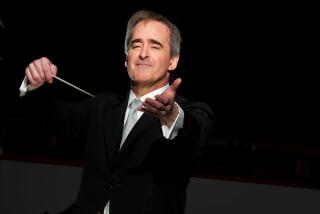

As some 40-year-olds find out, you can go home again, but sticking around may not be so easy. The Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra was founded in 1968 by British conductor Neville Marriner (although its first concert wasn’t until 1969), and Saturday night it began its 40th anniversary season with a special gala led by Marriner at the Ambassador Auditorium, where it once performed. But the concert was a one-time thing.

Marriner, who led LACO until 1978, is 84. Ambassador, the finest of LACO’s many homes over the years, opened in 1974 and barely escaped the wrecker’s ball after it went out of the concert business in 1995. Now owned by the Harvest Rock Church, it is, on occasion, rented out to student and Pasadena orchestras.

The very good news is that both conductor and hall are in remarkably good shape. Still sprightly and active, Marriner continues to head, and constantly tour with, the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, the famed London chamber orchestra he founded 50 years ago and the model for LACO. And however much Harvest Rock frustrates the Southland cultural community by making a wonderful venue too little available for concerts, the church deserves credit for scrupulously maintaining the facility. A drinking fountain I tried didn’t work, and there are now a pair of loudspeaker towers over the stage, but the place sparkles like new.

Entering Ambassador is like stepping into a time warp -- architecturally and design-wise, the building is the ‘70s looking back at the ‘60s and even ‘50s, evoking the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and the original, moat-surrounded Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Hearing LACO in Ambassador is, acoustically, also like returning to another era: that of rich, warm, analog sound. If the orchestra hadn’t sounded so good in years as it did Saturday, that was not because the playing was better than usual. The reason was that you heard the band so much better than in its current venues -- the dry Alex Theatre in Glendale and the less intimate (if decent-sounding) Royce Hall at UCLA.

The program was cleverly designed to remind us of the past without ignoring the present. Indeed, there was nothing from what Marriner used to jokingly call the Italian ice-cream vendor Baroque composers he made popular, such as Vivaldi and Corelli, when those names were little known by the general public. There wasn’t even any suggestion of his industrious service to the Mozart industry.

The concert began with the West Coast premiere of a new Schumann symphony. Sort of. Paul Chihara, whom Marriner made the orchestra’s first composer in residence way back when, recently wrote a slow movement, “Childhood Dreams,” to insert after the scherzo in Schumann’s Overture, Scherzo and Finale, creating a four-movement symphonic work.

Chihara took two movements from Schumann’s beloved piano work “Kinderszenen” (Childhood Scenes) as his source material and fashioned an attractive short rhapsody, with familiar melodies floating through thickish Schumann- esque orchestrations as if in a dream. I’m not sure that this is enough to make a convincing symphony, at least not compared with the four tightly woven, boldly conceived scores that Schumann did call symphonies. But neither is it a failed experiment. Taking a sweet breath in the midst of Schumann’s three strong movements does no harm.

The evening’s big work was Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto, with Jeffrey Kahane, LACO’s music director since 1997, as soloist. Kahane likes to conduct this imposing work himself from the keyboard, and the performance had a couple of uncertain moments when Marriner seemed almost in the way of Kahane’s flexible rubato. But the advantage here was that Kahane could put all his attention on his playing, which was stunning. Seated at a gleaming Fazioli piano, he brought to the young Beethoven’s showiest work to that point equal measures of glorious glitter and careful classical phrasing.

After intermission, Stravinsky’s “Pulcinella” was classic Marriner, lively but within reason. The playing here didn’t quite have the character or finesse that the orchestra regularly demonstrates under Kahane. But the final piece, Kodály’s “Dances of Galánta,” was downright seductive in its warmth and flexibility. Who knew that Marriner, in his 80s, had become a closet Hungarian?

A few members of LACO remain from the Marriner years. Oboist Allan Vogel, who joined in 1972, is the senior player. His solos in the Stravinsky were that performance’s most engaging moments.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.