Critic’s Notebook: L.A. Phil’s vision of Grand Avenue as a shelter for new work, ideas

Can Grand Avenue become an idea, or an attitude, as well as a place?

The Music Center at 50 is a mature performing arts center. Its newest venue, Frank Gehry’s celebrated Walt Disney Concert Hall — already an L.A. icon — turns 12 in the fall. Next year, the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Arata Isozaki building reaches its third decade. The Broad museum is almost finished. All this can be found concentrated within three blocks, clearly positioning Grand Avenue as one of the country’s most important arts destinations.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

L.A. Philharmonic: In the June 2 Calendar section, a column about the Next on Grand festival referred to an L.A. Philharmonic program for collegiate composers as the National Composers Initiative. It is the National Composers Intensive. —

------------

But despite a desire to modernize parts of its campus, the Music Center has put foresight on hold as it searches for a new president. It has thus been left to the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Music Center’s most prominent resident, to lead as well as properly celebrate the half-century anniversary. With the Next on Grand festival, the orchestra is doing just that, but it is also proposing a grander vision of Grand Avenue as a shelter for new work and ideas.

------------

FOR THE RECORD: A previous version of this column referred to an L.A. Philharmonic program for student composers as the National Composers Initiative. It is the National Composers Intensive.

------------

The centerpiece of the festival, which is focused on contemporary American music (and includes video, dance and opera), was a series of four programs by the L.A. Phil last week led by Gustavo Dudamel, to close the orchestra’s season. These included three major orchestral pieces commissioned for the occasion from three generations of American East Coast composers — 78-year-old Philip Glass, 59-year-old Steven Mackey and 39-year-old Bryce Dessner.

What may prove most noteworthy about the festival is how it has reverberated off Grand. It concludes over the next two weekends with “Available Light” — a revival of the 1983 collaborative work by Gehry, composer John Adams and choreographer Lucinda Childs that opened MOCA’s Temporary Contemporary (now Geffen Contemporary) in Little Tokyo, and Los Angeles Opera’s production of David T. Little’s “Dog Days” at REDCAT and part of the company’s “Off Grand” series.

The L.A. Phil brought the new music orchestra wild Up into the Next on Grand mix, with a concert Saturday afternoon at the funky Regent Theater, a rock venue a few blocks away on Main Street. Christopher Rountree conducted the premieres of works by feisty, fearlessly experimental college students participating in the L.A. Phil’s National Composers Intensive.

It wasn’t just the L.A. Phil that was busy with relevant programming. In Costa Mesa, the Pacific Symphony devoted its concerts last week to André Previn, who once was a very big deal on Grand Avenue.

These days, Previn wouldn’t think of setting foot anywhere near the Music Center. He is so bitter about his falling out with the late Ernest Fleischmann, the L.A. Phil’s general manager when Previn was the orchestra’s music director between 1985 and 1989, that Previn has said that he won’t even change planes at LAX.

I heard the Previn concert, conducted by Carl St.Clair at the Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall on Friday night, and it was wonderful. It included the West Coast premiere of a convivial new Double Concerto for violin and cello, written for Jaime Laredo and Sharon Robinson, with an irresistibly songful slow movement. Soprano Elizabeth Caballero was on the grand side for Previn’s song cycle “Honey and Rue,” but Toni Morrison’s texts could take it. St. Clair conducted vibrantly played performances of Previn’s sprightly “Principals” and the tranquilly touching “Owls.”

Previn’s gracious style might seem far removed from the L.A. Phil’s current Grand Avenue boldness, but had the L.A. Phil invited the Pacific Symphony to be part of Next on Grand (and why not?), Previn’s presence might have been grandfatherly appropriate.

Glass’ Double Concerto for Two Pianos, which had its premiere Thursday night, would not have found Previn’s new concerto an incompatible companion — two alluring double concertos by two of America’s most famous, most versatile and most populist composers. Dessner’s “Quilting,” also premiered Thursday, follows Previn’s example of moving beyond a pop sensibility into serious orchestral music, again without losing a populist touch.

But the most fascinating link is between Previn and Steven Mackey, whose “Mnemosyne’s Pool” Dudamel premiered Friday and repeated Sunday, when I heard it.

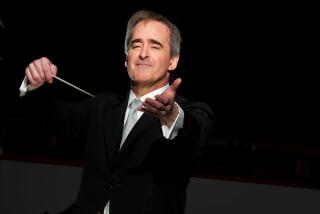

Named after the Greek goddess of memory, the magnificent, nearly 40-minute score is meant as a study in musical memory. But that may be little more than an excuse for a composer, who is also an electric guitarist, to give in to rapture. Straussian effusiveness and whiffs of melodic sentimentality keep escaping more effortfully than perhaps typical of Previn, but there is a distant kinship. Dudamel conducted an appropriately grand performance.

Sunday’s program began with “Shelter,” a collection of songs about housing by Michael Gordon, David Lang and Julia Wolfe (the founders of Bang on a Can). They were performed by a trio of vocalists and the new music ensemble Signal, conducted by Brad Lubman, and alongside a film by Bill Morrison. Although not all the visuals in the festival have been useful, these were, with gorgeously quiet evocations of homesteads, lonely landscapes and construction, with perhaps here the added symbolism of Grand Avenue as that shelter for new music.

The songs too, with ephemeral texts by Deborah Artman, found a moving common ground among Gordon’s rhythmic aggressiveness, Wolfe’s harmonic fullness and Lang’s quirky restraint. This reminded me of Previn’s film music, which sought to bring something new to a scene rather than to just tediously accompany action.

So while Next on Grand hearkens to an avenue of the arts that can become a national highway, let it also retain its foundation.

And may Next on Grand serve as another kind of example of the current Grand Avenue attitude fostered by the L.A. Phil. Roads are not built without resources. No other orchestra anywhere has a board with so many receptive members who consistently underwrite new works, such as these on the festival.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.