Riding to the rescue of L.A. Opera’s ‘L’Elisir’

It was, says Plácido Domingo, “truly a dream cast.” For this season’s opener, Donizetti’s “L’Elisir d’Amore” (The Elixir of Love), Los Angeles Opera had signed Mexican tenor Rolando Villazon and American baritone Nathan Gunn -- both marquee names -- as well as the young Georgian soprano Nino Machaidze. To top it off, the great Italian bass Ruggero Raimondi was going to mark his 45th year on the stage with his first appearance in L.A.

But then things began to go awry. Last spring, Villazon had to bow out because of vocal cord problems. And last week, Raimondi withdrew after rupturing an Achilles tendon during rehearsal.

“We will miss Rolando and Ruggero very much,” said Domingo, L.A. Opera’s general director, on the phone from Colombia. The company has found “wonderful singers” to assume their roles, he adds, “but it is still very sad -- and yet it is a part of life.”

Indeed, cast cancellations -- and the search for replacements -- are fixtures of the opera business. Tales abound of calamities, great saves and, as a silver lining, singers who got career boosts by answering last-minute calls.

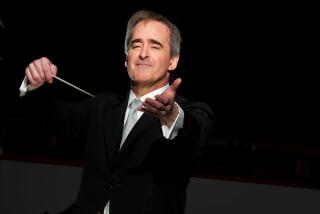

“Change is so normal it’s like, ‘If you water your grass, do you expect your grass to grow?’ ” said music director James Conlon, who will conduct “L’Elisir” when it opens Saturday. “You accept what happens and then you react -- lucidly.”

Singers are prone to sudden setbacks because their profession demands perfection in every note. “The most delicate instrument in the world is the human voice,” Conlon said. “You can go to bed, wake up and there is no voice.” Stage accidents such as Raimondi’s also are common. “Opera singers, like ballerinas or baseball players, are very active on the job.”

Performers must take care not to risk damage to their voices, while weighing which would be worse: the potential of delivering a sub-par aria or of disappointing fans with a no-show.

“It is a difficult decision because you always want to do your best,” Domingo said. “And you always want to think of the audience first.”

Domingo, who possesses star power and the largest repertoire of any tenor (130 roles), may be the ultimate white knight, having bailed out many companies, including his own.

One evening in 1989, he was set to conduct “Tosca” in L.A., but left the pit to sing when the tenor was indisposed. Six years earlier, the San Francisco Opera lost its Otello to laryngitis on opening night. Domingo, who was in New York, boarded a private plane and headed west. A gala dinner that was supposed to follow the show was served early and, as the audience ate, the tenor’s whereabouts were reported with precision worthy of a space mission: “Mr. Domingo is over Chicago. Mr. Domingo is over Las Vegas. Mr. Domingo has landed.” Domingo tried on costumes in the limo from the airport and was onstage when the curtain rose at 10:30 p.m.

The maestro, who also is general director of Washington National Opera, has made a few calls for help himself. What Domingo described as “my most desperate time” occurred in 1996, during his first season in Washington, when illness swept through the cast of “La Bohème.” After several colleagues had canceled one Saturday, the tenor announced that he, too, was going home. Having exhausted his resources covering other roles, Domingo was in a jam. He began to contemplate taking the part himself -- even though he was starring in a companion production, Gomes’ “Il Guarany,” and had sung the night before and was to sing the next day.

At the last moment, a tenor from another show was spotted eating dinner in a nearby restaurant. “He saved us,” Domingo said. “It was just like in a movie.”

Some ailing singers do go on, but ask that an announcement about their health be made. Some try to soldier on but end up withdrawing mid-show -- ideally, replaced by a cover, opera’s version of an understudy. On rare occasions, a performer will act out a role while a colleague sings from the side of the stage.

Conlon said that in Europe, where he worked for a quarter-century, covers are rarely used. Instead, the same-day scramble for replacements is a given. “There’s a rule: ‘If you are going to cancel, you cancel by 12 o’clock.” That system works, Conlon explained, because the proximity and number of singers make it “relatively easy to find someone suitable who can arrive in time.”

The U.S., however, has fewer singers and companies and the distances separating them are greater. So, covers often are hired -- although houses such as the Metropolitan Opera in New York, which has weathered a spate of cast changes in recent years, try to bring in big-name stars when they can.

Securing a replacement doesn’t always guarantee smooth sailing. While Conlon was conducting Verdi’s “Don Carlo” at Covent Garden in 1979, Welsh soprano Gwyneth Jones agreed to fill in on short notice. As he was standing in the pit, Conlon recalled, an assistant started waving and making snipping motions. “I thought, ‘What’s he trying to tell me?’ It turns out Gwyneth Jones didn’t know certain music because the opera is frequently done with cuts, which is how she had sung it.”

Word finally reached the orchestra, specifying the first trim. “I was conducting from memory, so I’m thinking, ‘Where was that exactly?’ ” Other cuts followed. “I did that all night, but it was an amazing experience.”

With “L’Elisir,” Villazon’s medical problems arose early enough for L.A. Opera to find a quality replacement in Italian tenor Giuseppe Filianoti, said Christopher Koelsch, vice president of artistic planning.

Raimondi’s departure was announced within two weeks of opening night. “We were fortunate in that we had a strong cover, [Italian baritone] Giorgio Caoduro, for Ruggero,” Koelsch said. “We don’t tend to cover all the major roles, which is not terribly great risk management but a matter of economics. But we had done it here.”

Otherwise, company officials would have quickly begun consulting colleagues and artists’ managers. “The operatic community is relatively small so we stay in touch regarding who can do certain roles and where they are in the world,” Koelsch said.

Since Caoduro had been hired as a cover, he knew his part (Dulcamara) and arrived for the last days of rehearsals. Even so, Conlon and director Stephen Lawless had to see how a newcomer affected the dynamics of the cast.

“Roles take on the qualities of the occupant,” Koelsch said. “It will be interesting to find out how things are transformed” -- given the differences in ages and styles between Raimondi, 67, and Caoduro, 28.

While losing someone of Raimondi’s stature leaves a shadow, Conlon said, it’s helpful that Caoduro already knows several of his new colleagues. “It lets us keep the wonderful atmosphere we have, which is important in comic opera because you want the joy of playing off each other.”

“Every combination of singers creates a different chemistry,” Conlon said. “We are creating a new balance, a new chemistry right now.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.