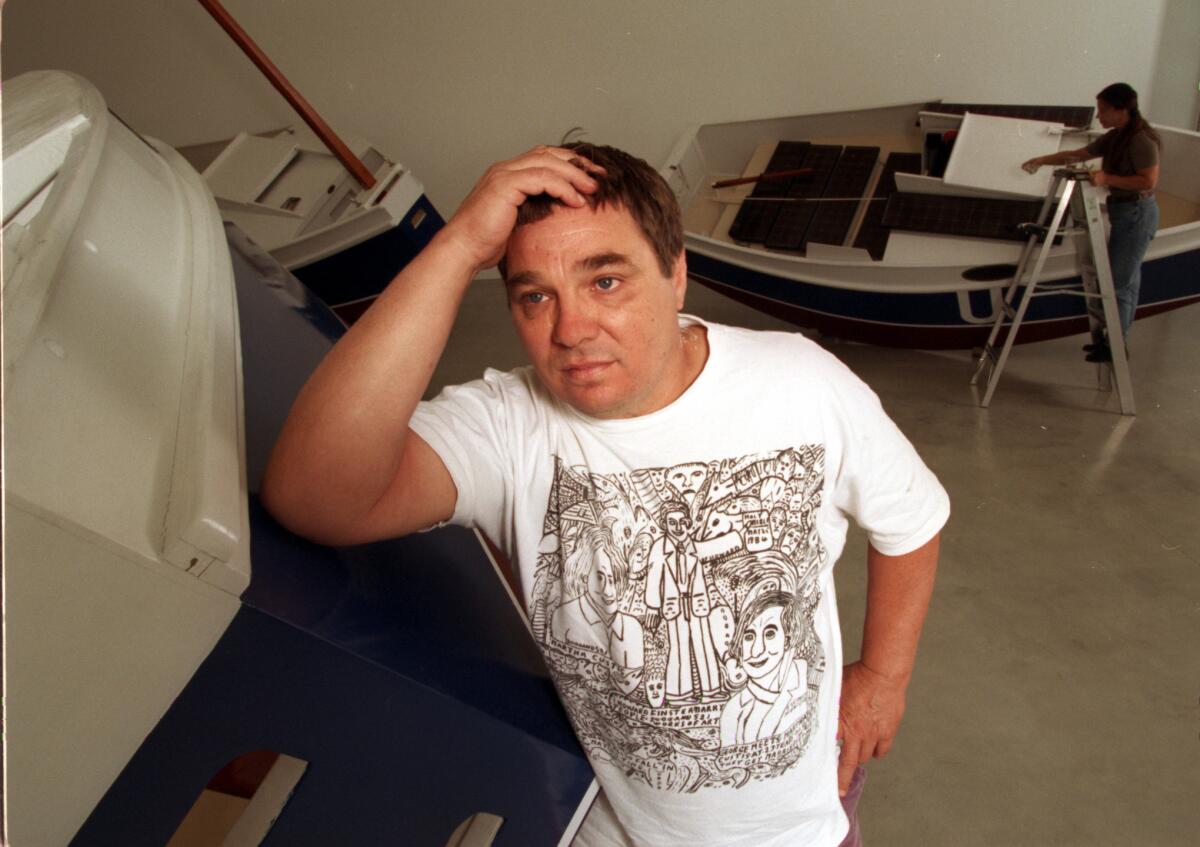

From the Archives: Unmasking Chris Burden: His art has always challenged the rules; for a while, so did his antics

Chris Burden is consdidered one of the most influential artists to come out of L.A. in the last 40 years.

There’s a pastoral calm to Chris Burden’s sprawling retreat deep in the heart of Topanga Canyon. One of a handful of Los Angeles artists to achieve international acclaim, Burden lives in a tastefully quirky Sunset-magazine-style house with his wife of six years, artist Nancy Rubins, and Guido, Fudge and Lulu, three large, greatly loved hunting dogs. Leading a visitor on a tour of his 27-acre parcel of land, a relaxed Burden offers, in a voice still marked by his boyhood Boston accent, a scientific explanation of how a bank of bright orange stones came to acquire their peculiar hue, identifies some unusual blooms in his cactus garden and points out a cluster of fruit trees. He has the air of a slightly offbeat country squire--formal, polite, somewhat shy and, except for his disturbing blue eyes, not at all what one would expect.

Where is the extravagantly florid anarchist who had himself shot in the arm in the early ‘70s and called it art? What happened to the brooding creator of dozens more outrageous performance pieces and other works that challenged not only basic notions of what is art but also took on politics, social issues and the terrors of the military-industrial complex? And where is the social renegade who earned a reputation in the early ‘80s for conducting his personal life with the same edgy aggression that made his art famous?

The answers to such questions come first from Burden’s work. The artist has definitely not stopped challenging the art world, or for that matter, the world at large. Burden’s 1990 piece “Medusa’s Head,” a roiling sculptural work depicting the Earth strangled by the Industrial Revolution, dominated “Helter Skelter,” the Museum of Contemporary Art’s survey of recent Los Angeles art that opened earlier this year. Some viewers and critics found “Medusa” ugly, others found it full of meaning, and The Times hailed it as one more push forward by Burden: “Leave it to Burden,” wrote Christopher Knight, “to invent a whole new genre, take it to a peak and bring it to a close, all in a single piece.” And another recent work, “The Other Vietnam Memorial,” a sort of monumental copper Rolodex naming not Americans killed in the war but enemy dead, was also alternately dismissed and hailed. “Agonizing,” said The Times in its positive review. “Its shocking moral ambivalence is the source of its riveting power.”

And Chris Burden the man has not quite lost his edge, either. A few days after leading the tour of his Topanga estate, Burden realizes that the reporter who’s traipsed into his life has also contacted several of his old friends and is poking into areas of his past and his personal life that he prefers remain unexplored. Prefer is actually not the word-- insists is more like it. Bristling and intense, the country squire adopts a frosty tone. If the volatile aspects of his private life are to be publicly aired, he warns in a series of phone calls, the story is off.

Eventually, calm is restored. But one thing is clear: Chris Burden may look like a mature, comfortable artist, one who has put his incendiary, anarchic days behind him. He may act like a quiet country squire, but he isn’t one.

BURDEN FIRST BLASTED HIS WAY INTO ART HISTORY IN SANTA ANA ON NOV. 19, 1971, with the performance piece “Shoot.” A friend with a .22 rifle stood 15 feet away, aimed, fired--and shot Burden in the left arm. It was supposed to be a flesh wound, but the bullet went into his arm, and Burden went into the hospital.

For the next four years Burden executed a series of precisely choreographed pieces that included having himself arrested, crucified, incarcerated, starved and all but electrocuted and drowned. Infused with a Jesuitical purity combined with a diabolical aggression, these carefully considered actions challenged the limits of metaphor in art and quickly achieved the status of legend. In one performance, he hung himself, naked, by the ankles in the Oberlin College gym, above the target-like center circle on the basketball court; in another, “747,” he stood on the beach near LAX and fired a pistol at a Boeing jet.

Burden operated like a guerrilla artist, staging his pieces with little advance word. Many of the early performances took place in his studio, documented only by his friends. As artworks, they were experienced largely as rumor--and Burden did manipulate rumor as a creative material. When you heard about a Chris Burden performance, an image would streak through your mind like a blazing comet. That was part of the point.

At first, the critics couldn’t catch up with him. And when they did, their take was a peculiar mix of head scratching, high-flown rhetoric and fear. Some observers found the work morally reprehensible and dismissed it as a form of conceptual terrorism; more than one critic called Burden the Evel Knievel of art. But even his staunchest critics conceded that there was a powerful mind behind the mayhem.

In the mid-’70s, Burden began to leave performance art behind, but the shift--to the largely sculptural forms that he continues to work in today--only solidified his artistic reputation. He made assemblages, mechanical objects, installations, models and dioramas and video works. And though the medium had changed, the work still bristled with rebellion, challenge and, according to one critic, “sheer nastiness.” Over the years, Burden addressed the arms race, ecology, money, AIDS, war fantasies and violations of confidentiality. In 1979, he covered the floor of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, a New York gallery, with 50,000 nickels topped with 50,000 matches, each unit representing one Soviet tank. He titled it “The Reason for the Neutron Bomb.” At the Rosamund Felsen Gallery in Los Angeles in the same year, another work encompassed his fascination with mechanical objects and metaphors for the System: “The Big Wheel” was an eight-foot, 6,000-pound, motorcycle-driven spoked monster that would spin for 2 1/2 hours after each ignition. His 1985 work “Samson,” at the University of Washington in Seattle, involved a turnstile, a 100-pound jack and a gearbox. As each visitor entered the museum through the turnstile, gears cranked the jack, increasing pressure on the museum’s structural walls and threatening to bring the hallowed hall of culture tumbling down. Throughout his career, Burden declined to construct a grand theory around his art. Journalist Jonathan Gold, who worked as Burden’s assistant in 1979 and 1980, says that sort of analysis just isn’t Burden’s style. “Critics would come to his studio, and I’d hear them reading all this stuff into his work, and he’d comprehend what they were talking about, but it didn’t have anything to do with why he made the stuff. It’s like rock ‘n’ roll--you can read a lot of theory into it, but those aren’t the reasons it came to exist. I remember Chris telling me, ‘My main, No. 1 rule is, don’t worry what it means--other people will figure that out--just make sure that it looks neat.’ ”

But if Burden resists creating a Grand Unified Theory, there are plenty of others willing to fill the gap. When the Newport Harbor Museum mounted a 20-year retrospective of Burden’s work in 1988, the accompanying catalogue included three thoughtful assessments of What It All Means and a host of cited references to other commentators who had come before. The weight of the catalogue, the seriousness of the effort and the simple fact of a traveling retrospective sealed what most observers had much earlier noted: Evel Knievel had been universally transformed into the Real Thing.

Artist Ed Moses, the critically acclaimed L.A. Abstractionist, has known Burden since his student days at UC Irvine and is unstinting in his admiration for his work. “Chris is inarguably the most powerful artist to come out of Los Angeles,” Moses declares. “Those early performances he did really peeled people’s brains. The question is, will Chris eventually be absorbed into the culture, or can he keep cracking the spine of the psyche? So far, he shows no signs of letting up, and that’s what’s so magnificent about him.”

IN HIS STUDIO ON A COLD, RAINY MORNING, BURDEN MOVES EASILY OVER AND under the odds and ends of metal that clutter the small space; in light of the reputation he’s achieved, his studio is modest indeed. Struggling to close a metal door in an attempt to warm the unheated tin shed, he discusses the trajectory of his career with matter-of-fact assurance.

“ ‘Shoot’ was a pretty important piece,” he declares as he fiddles with parts from an antique Erector set strewn about his worktable. “It worked well because it keyed into a fear we all share, which is of being shot. You can’t read about the shooting at the local market without realizing it could’ve been you.”

It was not, he says emphatically, about personal courage. Instead, he will admit, “a degree of denial” played a part in the process. “I’m not a particularly brave person,” he says. “In fact, I’m a chicken. I wear my seat belt. I wasn’t frightened when I was doing those pieces, but I was a little nervous in the days leading up to them--that was the hard part. During work like that,” he adds, “you achieve a state of intense lucidity and clarity and have a special kind of concentration. It’s not the same as having kidnapers put you in a footlocker, because you’re having the experience by choice.

“This isn’t to say I never felt any discomfort doing that work--I felt panic during a few of those pieces. With the platform piece (Burden spent 22 days on a platform built into the Ronald Feldman gallery for “White Light/White Heat”), I remember when I first went up there thinking, ‘Oh man, this is gonna be a long time. I don’t know if I can do this. What if I can’t do this?’ But what happens is you get more and more serene when you’re in a situation like that, and it gets increasingly pure and seductive. Those duration pieces are like a metaphor for life itself. When you’re young, life seems endless, but as you get older, it’s like, ‘Gee, it’s half over--this is going too fast!’ ”

The eldest of three children, Burden was born 46 years ago in Boston, where both his parents taught at universities--his mother was a biologist and his father was an engineer--and he remembers feeling “pressure to excel” at prep school in New England. But there were privileges with the pressures: While his father was a member of a think tank, the family spent six months in China.

When Burden was 10, his parents split up and his mother took him and his younger brother and sister to Europe. “A single woman traveling with three kids--it was pretty unsettling,” Burden recalls. “I was the oldest, so they stuck me in a boarding school in Switzerland for a year; that whole period was pretty traumatic for me.”

To hear him tell it, he became an artist by accident. During a trip to Italy when he was 13 years old, he was involved in an auto accident that crushed his foot. “It forced me to spend nine months in bed,” he recalls, “and I think it was during that period that I became an artist. Maybe that forced immobility allowed me to get in touch with the creative side of my personality.”

He started by taking pictures--” ’Family of Man’ style photographs” is how he describes them--but he ended up fascinated by Europe’s great cathedrals. “Those are some heavy-duty structures,” he says, laughing. Burden decided to become an architect.

Toward that end, he enrolled in Pomona College when he was 19. “But all it took was a summer working in an architectural office to turn me off to that,” he recalls. “It seemed like you had to be 55 before you got to make a decision. At the end of summer, I returned to school and saw the sculpture lab and thought, ‘With this you don’t have to wait--you get an idea, then you make the thing.’ That suited me perfectly.”

Burden came of age in an era when the art object was in the process of either stripping itself down to Minimalism or dematerializing altogether into Conceptualism. Studying at Pomona under Minimalist sculptor Mowry Baden, who also espoused the Dadaist position that ideas are more important than objects, Burden absorbed elements of all three of those styles, then developed a mix that led him ultimately to “Shoot.”

Burden saw his switch from sculpture to performance as a logical extension of Minimalism. “I never saw the performance work as moving away from Minimalism--I saw it as a way of honing in on what Minimalism was and of posing the question, ‘What is sculpture?’ ” he explains. “Sculpture is three-dimensional, and you have to walk around it to see it--that’s the main thing that distinguishes it from two-dimensional work. That led to the question of whether sculpture is the object produced by activity, or is it the activity itself? I decided sculpture was the activity, so in a sense I was becoming more Minimal in eliminating the object.” Such a radical approach to art was very much in keeping with the graduate art program at UC Irvine, where Burden earned an MFA studying with Conceptualist sculptors Robert Morris, Tony Delap and Robert Irwin.

“Obviously I didn’t teach Chris--I spent time with him,” says Irwin. “Most of the time I didn’t have the slightest idea why he was doing what he did, but I immediately recognized he had a strong and unique sensibility and that he had a good handle on what he was doing.”

Not everyone is so hesitant to analyze Burden’s developing aesthetic. “I wasn’t surprised when Chris started doing performance work,” recalls landscape architect Regula Campbell, who met Burden on the first day of school at Pomona in 1965, “because I saw the roots of that work in his personality all along. He had an extreme personality--he wanted to be extreme--and he always had a streak of exhibitionism. We all wanted to be Angst -ridden and were fascinated by the dark side of things then, and Chris and I both had motorcycles we used to roar around on.” Campbell was present at some of Burden’s scarier events. When she looks back now, she shakes her head: “When you’re young,” she says, “you never think that people can get hurt.” Barbara Burden, Chris’ former wife, also witnessed most of the performance pieces. “I was convinced then--and still am today--that those were great artworks,” she says, “but I still tried to talk him out of doing them. Obviously, I was never successful,” she adds with a laugh. “His friends never tried to prevent him from doing the work, and he always found people willing to help out, particularly as he continued to work in the same way. People began to realize he was a serious artist and not just some nutty guy.”

It was in 1974 that performance art began to wear thin for Burden. By then, the media had caught up to him, and critics eagerly awaited each production. “People were starting to expect certain things of me, and I didn’t want to get boxed in by that,” he says. “The press was getting kind of hysterical, and I knew if I kept doing that work I was going to be turned into the Alice Cooper of art. Sensationalism was never what that work was about.”

Still, Burden’s performances would continue sporadically through 1980, but by 1975 he was branching into other media, and in two months that year, he put together “B-Car,” a from-scratch functioning automobile-cum-artwork.

“That was the turning point,” says Burden of the car, which looks a little like a cross between a soapbox-derby entry and an early Indy racer. “B-Car” signified a return to sculpture, and it was also a sign of his growing fascination with various forms of hardware and technology--wheels, gears, engines, vehicles, boats, planes, weapons and all manner of other toys. When “B-Car” opened in New York, though, all it garnered was a fistful of California-bashing reviews.

Once again, the early returns were wrong. The car ushered in a 10-year period of consolidation for Burden; grants had just started rolling in (there would be four from the National Endowment for the Arts and one Guggenheim), he landed the plum artists’ gig, a university teaching job, at UCLA, and he worked on a slow but steady schedule of exhibitions and installations.

At the end of the ‘80s came the retrospective in Newport, and from the vantage point of 1992, Burden looks back with gratitude. “The retrospective was a good thing for me,” he says, “and I did pretty well in the ‘80s. Because there was so much money churning through, and everything was popping, there was a lot more opportunity for guys like me, who aren’t marketable.”

The proceeds from sales and commissions from that time period financed Burden’s next really big splash, “Medusa’s Head.” He began the sculpture in the living room of his house. “But,” he says, “by the time the plywood frame was finished, it was so heavy that the house was making weird noises.” He and his chief assistant on the project, Tim Quinn (“It’s my vision, but it’s the assistants’ hands,” says Burden), hefted the sculpture outside and into the shed. Ultimately, it was transported to a workshop in the Valley.

“I thought it was going to take three or six months to make the thing,” he says. “It took two years and a lot of money--$250,000, as much as my house cost.”

The piece was first shown in 1990 in Whitechapel Gallery in London, where it bombed completely. “The British press was totally outraged by it,” Burden says, relishing the story. “They said it was big and arrogant and just looked like grimy industrialism. ‘The audacity! The sheer size of it! How dare he!’ The piece was damaged when it was in England, and the press said it was punishment for my ‘hubris.’ ”

On this side of the Atlantic, though, the piece has been more successful, and it put Burden back into the news the way nothing had since the performance pieces years before. Still, the words that ended up in print were not what you could exactly call kind: “scorched earth,” “bad-boy spirit,” “big festering skull.”

Burden, on the other hand, finds the piece beautiful. He uses the word liberally to describe the five-ton sphere that is now disassembled and packed away. He wishes someone would buy it, not so much for the money, he claims, but just to give it a home.

“It’s a scary piece (for the marketplace),” he admits, but then a few ticks later he’s back to beauty. “It turned out better than I originally envisioned, and I’m really happy with it. At MOCA once, I saw it in the morning, and the sun was positioned so that it was all lit up, and I thought, ‘This thing looks good .’ ”

AS FORTHCOMING AS CHRIS BURDEN CAN BE WHEN DISCUSSING HIS WORK, HE’S quick to erect barriers when it comes to his private life and positively closed-mouthed when it comes to any sort of deep analysis of his character.

Intensity is the word that appears in the hesitant evaluations made by Burden’s friends. His ex-wife Barbara Burden uses it, Regula Campbell uses it, and so does Jonathan Gold. Phyllis Lutjeans, a friend of Burden who hosted a cable TV talk show in the early ‘70s, once invited him to do a performance on the air. What he did, without warning, was hold Lutjeans at knifepoint for several minutes in an attempt to violate the taboos of the broadcasting medium.

“When Chris put the knife at my throat, I was absolutely terrified,” Lutjeans recalls. “I thought, ‘This guy’s psychotic.’ It didn’t affect my feelings about him,” she’s quick to add. “I thought he was a great artist then and I still do.” But she also says, “Chris never apologized to me for doing that.”

There came a time when Burden’s ferocity bled from his art into everyday life. His first marriage ended in divorce in 1977. Burden then began a four-year romantic relationship with artist Alexis Smith, after which he became involved with another artist, Mary Corse.

Their split, in the early ‘80s, seemed to launch Burden on a downward spiral that he is reluctant to discuss and that his friends will confirm only in broad strokes: a fascination with intoxicants, guns and complicated romantic liaisons. Burden greets questions about that period with a pained expression that discourages further probing.

“That was really a bad time for Chris,” says Jonathan Gold. “When you realize you’re the artist, you give yourself permission to do stuff, and that can be a dangerous place to be. I think that’s when he was finding out what his own limits were.”

Adds Paul Shimmel, who is now senior curator at MOCA and who curated the retrospective of Burden’s work at the Newport museum in 1988: “I met Chris in the early ‘80s, and it’s true that was a terrible time in his life, but I think part of that was just the times.”

Burden’s friends use words such as frayed or bully , and more than one says he was “self-destructive.” But everyone also agrees on two things: The extremes are behind him now. And just as some of them traced his earlier problems to his relationship with a woman, most of them now trace the solution to another woman, his wife of six years, artist Rubins.

“He’s a lot cooler now, less desperate,” says Ed Moses, “Nancy is a fabulous woman, a fabulous artist, and she’s had a tremendous effect on him.”

“I think Chris has always learned from the women he’s been with,” says Shimmel. “For instance, I don’t know if he would’ve done the collages he made in the late ‘70s had he not been with Alexis Smith. And Nancy affected him very dramatically. He’s calmed down a lot. They have a great marriage--it’s a really caring, productive relationship.”

Burden’s relationship with Rubins, whom he met while both were teaching at UCLA, does seem to have provided him with a stability he’d long been searching for. Their marriage in 1987 roughly coincided with three other pivotal events in Burden’s life; the 20-year retrospective of his work, the building of his house in Topanga Canyon, and the deaths of his younger sister in 1987 and his younger brother in 1991.

Talking about his family and his marriage are mostly off limits, but Burden will say that the death of his brother and sister changed him. “It made me feel lonely, more conscious of mortality,” he says. He also indirectly confirms that Rubins has had a calming effect on him. “Being happily married,” he says, “you have more time to do your art and less time to thrash around.”

There is one area of his personal life about which Burden is loquacious--the Topanga property and its healing powers. He bought the land in 1981, but it wasn’t until 1984, after he and Rubins began their relationship, that they moved out to the land together. The house wasn’t completed until 1988.

“We had to have a road put in,” Burden recalls, “and after that was done in the spring, Nancy and I started camping out here and spent the summer on a platform I built. We had a spring that worked then, but we didn’t have electricity or a phone, and we lived that way for about a year. Then we built these big tents and lived in those for three years. It was great--I felt like I was in Montana or something, but we were right next to a city of 12 million people, sleeping outdoors on a piece of plywood.

“I often stay out here for days at a time,” he says quietly, “without going into town. Going down to the mailbox is a big event out here.

“One of the biggest challenges I’ve dealt with in my life was finding a place where I felt comfortable. Bouncing around from place to place, I always felt a little lost, so moving out here and putting down some roots really meant a lot to me.”

THE FIRST FLOOR OF THE TOPANGA HOUSE IS DOMINATED BY ONE BIG LIVING room with lots of windows and a Burden assemblage in progress called “Pizza City.” He has been fiddling with it for six years, grouping and regrouping thousands of miniature buildings, cars, bits of landscape. The setup requires painstaking care, but it is infinitely rearrangeable, and Burden “plays” with it when he pleases. “Then,” he says, laughing, “one of the dogs will run through the room and knock it all apart.”

Outside, an antique steamroller sits a few yards from the house, along with several junked cars, a kayak and an astonishing installation piece by Rubins built out of scraps of salvaged metal intertwined with a large tree. Where it isn’t Topanga wilderness, vegetable garden or orchard, the landscape is rusting industrial junk. It’s all raw material for Burden--a good part of his days (he has been on leave from UCLA for the last year or so) are spent puttering amid the cultural debris. “For me,” Burden says, “tinkering is like sketching.”

Since “Helter Skelter,” two of his pieces have gone on exhibit in Los Angeles at the Lannan Foundation: “The Big Wheel” and “The Other Vietnam War Memorial.” The foundation purchased the former and funded the commission for the latter for its permanent collection. And back at Topanga, Burden constructed a smaller version of “Medusa’s Head”--”Medusa’s Flying Moon”--and another entry in his informal series on modes of transport, this one called “Noah’s Arc” and made of old bicycle frames. Both were scheduled for a show at the Fred Hoffmann Gallery last spring, but the gallery closed, and the pieces have not yet been shown. At the moment, Burden has no shows in the works. His most recent dealers, Donald Young in Seattle and Josh Baer in New York, are no longer doing business with him; one place where the abrasive side of Burden’s personality still shows up is in his dealings with gallery owners. His latest liaison is with New York dealer Larry Gagosian; the rumor is that Gagosian is financing a Burden piece titled “Fist of Light” for next year’s “Biennial” at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

Sitting in his wide-open living room, Burden speaks philosophically about his art, its worth, his reputation. Characteristically, there is no complete assessment here, only clues. He knows what he wants: “A place in history.” He knows what he’s aiming for: “When I see a good work of art, it stays with me and tickles some aspect of my mind. I think about it for a long time afterward, and it keeps coming back.” And he knows the way to justify the work he has created: “Art doesn’t have a purpose,” he says with a shrug. “It’s a free spot in society where you can do anything.”

Burden leaves it to others to define that free spot. Ed Moses, for one, doesn’t hesitate.

“Chris is the perfect embodiment of my idea of what artists are--they’re magic people,” he says. “In a tribal situation the magic man or the weirdo had a place in the tribe and was considered blessed, but there’s no real outlet for magic in America. We don’t have magic here--art’s just a groovy thing to do--and because of that, a person like Chris will inevitably be in conflict with the environment around him and will remain outside the mainstream. I have no doubt Chris will continue to make work that splits things wide open because it’s in his nature to do that.”

Kristine McKenna frequently writes about art for The Times

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.