Q&A: Jeffrey Herr on restoration, trash digging at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House

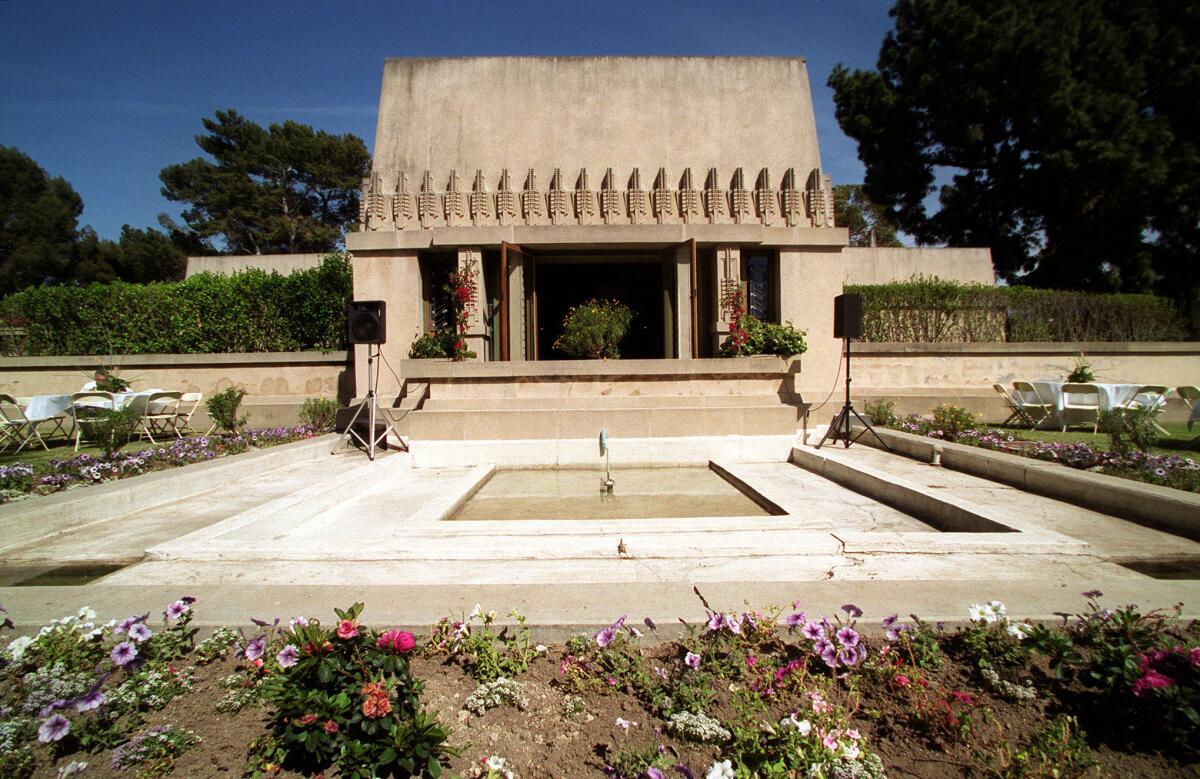

In 1921, the finishing touches were put on an unusual, temple-like structure at the top of Olive Hill in Hollywood. Hollyhock House, as the building was called, was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright as a home for an eccentric Pennsylvania oil heiress by the name of Aline Barnsdall. The practically Mayan structure was unlike any residential structure then built in Los Angeles -- and unlike anything Wright had designed before. In a 1933 story on the house, The Times reported that the architect had “a particular flair for breaking up the ordinary lines of construction.”

Now a National Historic Landmark -- and a part of the Barnsdall Art Park Complex that overlooks Los Angeles and the Hollywood Hills -- the Hollyhock House recently underwent a six-year, $4.4-million renovation to take care of the many leaks and drainage problems that were plaguing the structure. In the process, a number of design fixes have been also been made. (Over the decades, sundry renovations stripped away important architectural details.)

On Friday, after a ribbon cutting by Mayor Eric Garcetti, Hollyhock once again opens to the public -- but this time, looking much as she did when Barnsdall first opened the doors to her unusual new home in the early 1920s.

Jeffrey Herr, curator of Hollyhock, helped oversee the whole renovation. He took time to speak with me about what makes the house so special, the surprises they found along the way and how, through a little sleuthing, they were able to re-create important period details.

There have been a number of previous renovations done on the house, including one that was completed quite recently, in 2005. What needed to be done this time?

That last renovation was Northridge earthquake mitigation. It focused on rectifying all kinds of damage caused by the [1994] earthquake. There was a lot of preservation work done at the time, but I wouldn’t say that they were actually doing restoration in the way that this particular current program was approached.

This time, our No. 1 focus was to correct the leaking roofs and the drains that were clogged -- all the water issues, really. In the process, we were going to have to access the roofs and the drains, disturbing a lot of interior surface space. The question was: Do you return it back to the way you found it? Or is there a possibility to do something else? Can we go back to an earlier period in time? Our answer was, if we are able and have the information necessary, we want to go back to 1921.

Los Angeles has a number of houses by Frank Lloyd Wright. What makes this one so special?

Well, within the context of Wright’s career, it’s the first house of his second period -- post Prairie-style period. It’s also his first house in Los Angeles. That means it’s the first time he gets to experiment with Japanese-inspired ideas of dissolving the walls between the exterior and the interior. Here, he’s got a climate he can do that in.

Beyond that, Wright is designing for an unconventional client. So it’s not a conventional house. Wright has the ability -- if not the mandate -- to actually design something that is very different. And what happens in that process is that he begins to use interior space for residential living in a very different way. It influences his later work. It influences the work of his project manager, who is [architect] Rudolph Schindler. And it influences the career of Schindler’s friend and colleague, Richard Neutra [also an architect].

What makes the interior residential space such a departure from previous designs?

What you get is the very early genesis of what can arguably be said to be the California Modernism movement, the Ranch-style house in America. Now, you’re not going to walk in and say, “This is the first Ranch-style house in America.” Not at all. But it conceptually leads to that.

In homes prior to Hollyhock, the architect brings you to the entry hall and provides clues about where visitors go next: usually a parlor or a living room, where the stranger would be greeted by the owner. Walk into Hollyhock House and the foyer doesn’t even have four walls. And it’s very confusing as to where you might go. It’s visually very open. It’s not an open-plan house. But it’s a lot more open than the Craftsman bungalows or Spanish colonial homes or Queen Anne architecture, which were being built at the time. All of that architecture is really quite more rigid in terms of interior space.

What was Aline Barnsdall like?

Well, she was quite unconventional. She wanted a theater where she could produce avant-garde plays. She was a single parent by choice. (She wanted a child, but not a husband.) She was a philanthropist: She was one of the founding members of the Hollywood Bowl, for instance. She was a political radical -- she supported an anarchist named Emma Goldman. Barnsdall had her very own FBI dossier. She was also an art collector. And when I say collector, we’re talking about a collection that would have rivaled those of the Mellons or the Havemayers.

She met Wright in Chicago. She probably would have seen Midway Gardens [an entertainment center Wright designed there that is no longer standing]. And I think she would have looked at Midway and said, “No one else is doing anything like this. I want something unique. I don’t want another Beaux Arts proscenium theater. I want something that conceptually reflects my ideals.”

-----------

FOR THE RECORD

8:09 a.m.: An earlier version of this column stated that that Midway Gardens in Chicago was an apartment house. It was an entertainment center.

------------

She pre-named the house Hollyhock before it was even designed because it was her favorite flower. Wright didn’t have to incorporate that. But it must have sparked a germ of an idea because he went off the deep end with that and you can find it in many instances in the house.

Barnsdall ultimately fired Wright.

Well, if the architect says it will cost $50,000 to build and it costs three to four times that, it can make you cranky.

At this point, he wasn’t working with textile blocks yet -- like on the Ennis House, from 1924. Can you tell me about the materials he used on Hollyhock?

He had played with the textile block system on paper, but he hadn’t executed anything yet. Hollyhock was supposed to be poured concrete. But that would have been excessively expensive. So he chose a common building material: a hollow clay tile.

What would you say are the home’s most significant design features?

First of all it dominates its site rather than becomes a part of the site. It’s a hilltop temple. It’s monolithic. It has such presence. And it has this hint of exoticism to it. You have Frank Lloyd Wright, whether consciously or subconsiously, referencing pre-Columbian architecture. He writes about wanting to design a house that is a California house. What makes the house so amazing is how theatrical it really is. It’s lush. It’s exotic.

But it lost that over the years. It became beige. That’s one of the real treats of this recent restoration is to bring back and restore that lush exoticism to the interiors. So that when you walk in, you don’t feel like you’re walking into something from the late ‘70s or early ‘80s where everything is beige. With Frank Lloyd Wright, it’s all about details -- design details -- and they’re all integral to the whole. If you’re missing one, you might not notice. But if you’re missing a whole menu, then you might not have the same building.

What do you mean that the home became “beige” over the years?

There were major details that literally got lost in the 1946 renovation -- an enormous amount of ceiling moldings. That’s been an important theme in Wright’s interior designs. So restoring those restored proportion to the house. In this case, we’re re-creating something that was lost over the time -- especially in the porch area. The wall moldings there had been obliterated. Re-creating them was a significant improvement in terms of bringing back Wright’s original designs.

How do you go about re-creating something like that which has been lost?

You start with a few bits of information. We started with some photographs, some snapshots that Aline Barndsdall took. And we were able to find other photographs that had been taken — some photos from 1945 by a photographer named Will Connell. I managed to track down the repository where the negatives came from. When they did the restoration in 1974, they didn’t have digital photography and they didn’t have computers where they could enlarge detail. But having the original negative, you can scan it in. In a photo, where there might be large black areas, the negative might have more information. And you can manipulate it and get the detail.

We were also able to locate a sheet of millwork with specifications and it allowed us to reproduce some of the ceiling moldings. In the photograph, they looked just like flat wall moldings. But when you look closer at the specifications, you see that a part of the decorative design protrudes. It’s a detail that makes a huge difference, especially at night, when the light reflects off of the pieces. It’s much more alive than if everything were flush.

What’s the most startling discovery you made throughout the whole process?

There really were a lot of vital clues that came up. We have some planters in the foyer and opposite on the other side, in the living room. One day I looked in and thought, there’s just a bunch of trash in here and it should be cleaned up. So I started cleaning them up. Well, it turns out that in the 1940s renovation, some of the workmen used [the planters] as a trash bin. And, as a result, they contained bits of plaster fragments from the house — so we were able to know what the original plaster and colors were like. It’s pretty phenomenal when you realize you’re looking at.

I understand that you are now trying to track down furnishings for the home. What are you looking for in particular?

I’m always working on furnishings because that’s what I really like. I’m always, always looking for objects that are identical to the ones Aline Barnsdall owned and used to decorate the house. There are also some Frank Lloyd Wright-designed pieces of furniture that we know existed but we don’t know where they are today. So we are reproducing them so that people can get a sense of what the house looked like when Barnsdall lived there. The living room furniture has been reproduced. But there are some tables that she had that I’m still working on.

How has this whole process changed your view of Hollyhock House?

I think I’ve learned to love Hollyhock House -- not just respect it. There’s an emotional connection that I did not have before. It was completely intellectual. Working on this and seeing it spring to life has made that an emotional connection.

Hollyhock House at Barnsdall Art Park reopens to the public for 24 hours of self-guided tours from Friday at 4 p.m. to Saturday at 4 p.m., after which it can be visited via tour. 4800 Hollywood Blvd., Hollywood, barnsdall.org.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.