With swagger and style, Jose Montoya’s drawings at the Fowler document Mexican American life

When the artist, poet, activist and educator José Montoya died in 2013, he left a treasure trove of drawings in his Sacramento studio. The sketches — some 4,000 of them, accumulated over more than half a century of travels around California and beyond — were created on just about any material the artist could lay his hands on.

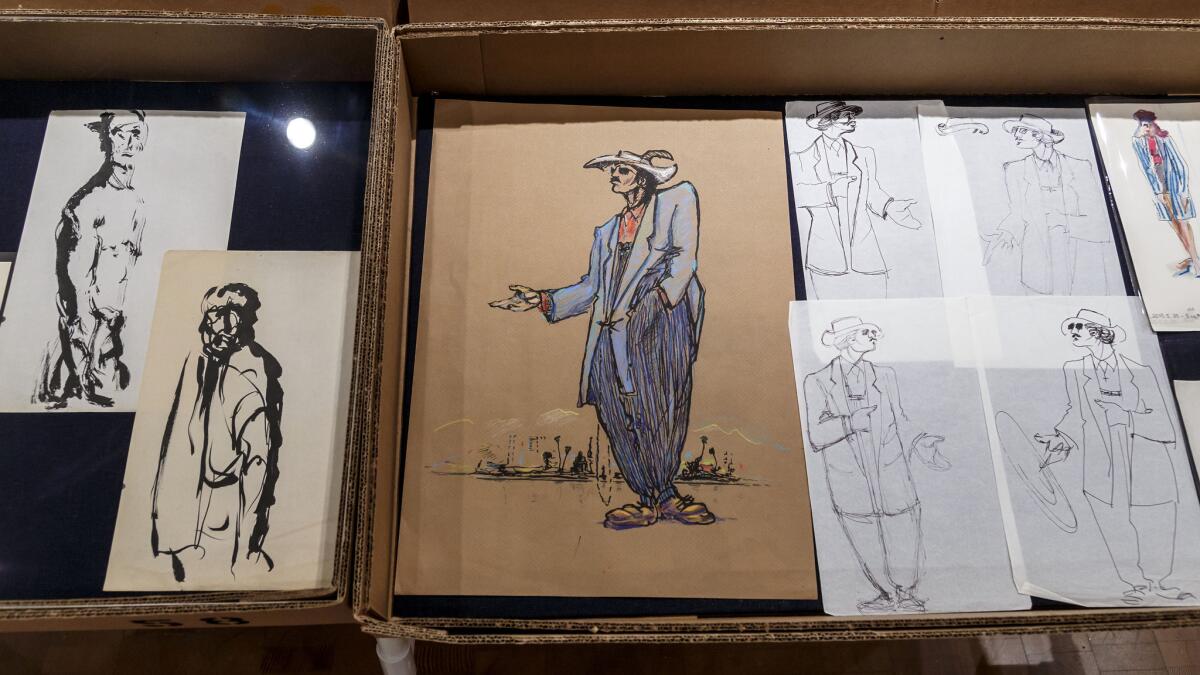

There are sketches of dogs on stationery from a Hilton Hotel in Oregon. There are self-portraits on 8-by-10 copy paper. And there are pachucos and homeboys, elegantly rendered on paper towels and restaurant napkins in their zoot suits and bandannas, figures who stare down authority with style and swagger.

Over the course of his life, Montoya repeatedly drew pachucos in their zoot suits — capturing the flamboyant elegance of a fashion that was also rooted in resistance.

There isn’t a scrap of paper that didn’t serve as canvas for Montoya. One drawing, a portrait of a man and a woman, their thoughtful profiles rendered in red ink, was sketched onto an expense list for an ethnic studies symposium at some unnamed institution. Chances are it was Cal State Sacramento, where Montoya was a longtime professor of art, photography and education.

“All of these were in his studio in Sacramento, boxed and stacked away,” says his son Richard Montoya, the actor, director and cofounder of the performance group Culture Clash. “We always knew they were there, but we didn’t know how many.”

For the past two years, Montoya, along with independent curator Selene Preciado, have been dutifully going through the pile for an exhibition of Montoya’s drawings at the Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Upon his death, José Montoya left thousands of drawings in his studio. The artist’s son, Richard (above), who co-curated the show at the Fowler, helped sort them all.

“José Montoya’s Abundant Harvest: Works on Paper, Works on Life,” which opens this weekend, is the Chicano artist’s first solo museum exhibition and the first ever to gather the staggering breadth of his drawings into a single show. (“Abundant Harvest” will display roughly 2,000 of his sketches.)

“The only way to get through all of it was to just dive in,” says Richard. “There’s a method to the madness and a madness to the method. I just had to embrace that in order to do this.”

José Montoya was born in 1932 on a ranch outside Albuquerque and moved to California’s San Joaquin Valley as a young boy. By the time he was 9, he was working in the fields alongside his relatives — picking, among other things, grapes, the fruit that would become the symbol of the farmworkers’ struggle in the 1960s.

For the display, the Fowler’s curators have organized Montoya’s voluminous drawings into a series of fruit boxes on the gallery floor. These pay tribute to the artist’s agricultural roots.

Members of the family, known for its work ethic, were dubbed quinienteros (roughly “of the five hundreds”) for their ability to pick 500 trays of grapes a day. The exhibition honors this history by presenting Montoya’s drawings in tidy rows of cardboard fruit boxes (which also has the effect of cleverly breaking up what could be an overwhelming number of works).

“It’s a metaphor for the fields,” says Fowler director Marla Berns. “Wherever he was, he seemed to have a pen in his pocket to capture the moment. He made so many drawings. So the notion of abundance is apt. It relates to a harvest.”

Despite the grueling nature of life in the fields, Montoya’s mother nonetheless found ways to inspire artistic interests in her children.

“Back then, the fruit would be laid out on these long sheets of butcher-type paper in the boxes,” says Richard. “My grandmother would roll up several pieces of paper and she’d take it back to the tent or whatever space they were living in and teach the kids how to draw.”

Rows of Montoya’s studies of female heads grace one wall at the Fowler.

From an early age, Montoya seemed destined to work in something other than agriculture. In “Resonant Valley,” a poem he wrote in 1969, he describes himself as ill-suited to the task — more conscious of the tiny creatures that might die along the way than in keeping up with the harvest:

“I was quick to / Sadden at the sight / Of the green, iridescent worm / Scorching itself in the / Hot, planned-for-tray, sand. / And knowing I had something / To do with its death / I wept.

Montoya became the first in his family to go to high school. And after a stint in the Korean War, where he served on a U.S. Navy minesweeper, he attended the California College of Arts and Crafts in San Francisco and later Cal State Sacramento, where he earned a master’s of fine arts.

He worked as a teacher and professor, but was best known for being a cultural polymath who seamlessly united activism, art and writing.

He penned lyrical stanzas about the Mexican American condition in English, Spanish and Spanglish. One of his best known poems, “El Louie,” tells the story of a zoot suiter who struggles to reassimilate after serving in the Korean War:

“And on leave, jump boots shainadas and ribbons, cocky from the war, strutting to early mass on Sunday morning. / Wow, is that el Louie.”

Montoya also campaigned tirelessly for the cause of Chicano civil rights and the rights of farmworkers. (Richard recalls watching his father sketch Cesar Chavez at the dinner table on one occasion.) To this end, the artist and several colleagues founded the Royal Chicano Air Force, an art collective that created posters and staged actions in support of la causa.

As with so many things that Montoya touched, it was infused with humor. The group had begun life as the Rebel Chicano Art Front, or R.C.A.F. — until one day someone asked them why they were referring to themselves as the Royal Canadian Air Force.

“They loved that idea — of the pilots and the regalia, so they began calling themselves the Royal Chicano Air Force,” says Richard. “They would travel in this fleet of Volkswagen buses wearing pilot regalia. It was so theatrical. When they would go into places like Delano, they would just rout law enforcement and the Teamsters. They were fearless.”

Throughout all of these adventures, Montoya sketched, drawing images of agricultural buildings, farmworker cantinas, stylish lowriders, activist meetings, zoot suiters, sexy pachucas, friends, family, pilots and Aztec warriors.

One of the oldest images in the exhibition, from 1959, shows Montoya’s car broken down on the side of the Grapevine — a testament to his playfulness, even in moments of mechanical frustration.

Richard Montoya, with Fowler Museum director Marla Berns, reviewing some of his father’s drawings of pachucos on napkins.

In the immediate wake of his father’s death, Richard says the first drawing he came upon was an image of a man on his hands and knees. It’s an ambivalent work — impossible to tell if the figure is standing up or falling down.

“I thought of it as a figure that is getting back up,” says Richard. “That’s what saved me.”

Preciado, who, with Richard, spent the better part of two years sifting through Montoya’s thousands of drawings, the majority of which were undated, says they offer an intimate view of the artist’s world.

“The practice of drawing is so personal and intimate,” she says, “you see the thinking process.”

“And there’s this humanity,” adds Preciado. “You can identify yourself in them, regardless of background .... He was making a portrait of the community and his people and the struggle.”

Montoya, inadvertently or not — through drawings, poetry and his writings — was recording the daily life of Mexican America during turbulent times, capturing the ordinary, the beautiful and the sublime from within a community that is often invisible in mainstream media and arts institutions.

“The storytelling is so relevant in his work,” says Richard. “He was dialoguing with farmworkers, with [John] Steinbeck, with the Beats, with [Mexican essayist] Octavio Paz .... He is telling the story of his people.”

Berns, who met the artist through a show of Chicano graphic posters at UC Santa Barbara in 2001, says she is happy to see someone like Montoya get his due.

“Drawings are such an important way of seeing an artist, of understanding their thought process,” she says. “He was so observant. He always had a sense of humor. But he was also quite subtle.”

Richard, in the meantime, is excited to have the public interact with work that had long lain in boxes.

“There’s a bit of the brilliant madman to my dad,” he says. “This, in a way, is my tribute to him.”

“José Montoya’s Abundant Harvest: Works on Paper, Works on Life” opens at the Fowler Museum on Sunday and runs through July 17. UCLA, 308 Charles E. Young Dr. North, Westwood, Los Angeles, fowler.ucla.edu.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.