Q&A: Why Star Montana wants you to really see Boyle Heights through her stark and stirring portraits

Star Montana remembers the exact moment she decided to become a photographer.

“I was 16 and I was a wild child,” says the artist, who was born and raised in Boyle Heights.

Around that time, a good friend had enrolled in a photography class at nearby East Los Angeles College.

“She was doing a creative black-and-white class and she showed me these images,” Montana recalls. “And I said, ‘I want to do this.’ She said, ‘Do it.’”

That was all it took.

Montana made for a local swap meet where she picked up an old 35mm camera and got shooting. Since then, she has steadily produced stark yet intimate pictures that record the lives of her close friends, family members and the countless individuals who cross her path around her neighborhood and in greater Los Angeles.

At one point, quite poignantly, she chronicled her own mother’s death, images that were shown at the Vincent Price Art Museum early last year.

As part of her process, the artist interviews her subjects and records their stories, which she recounts in texts that are displayed alongside her images. These frequently acknowledge her own fractured family history.

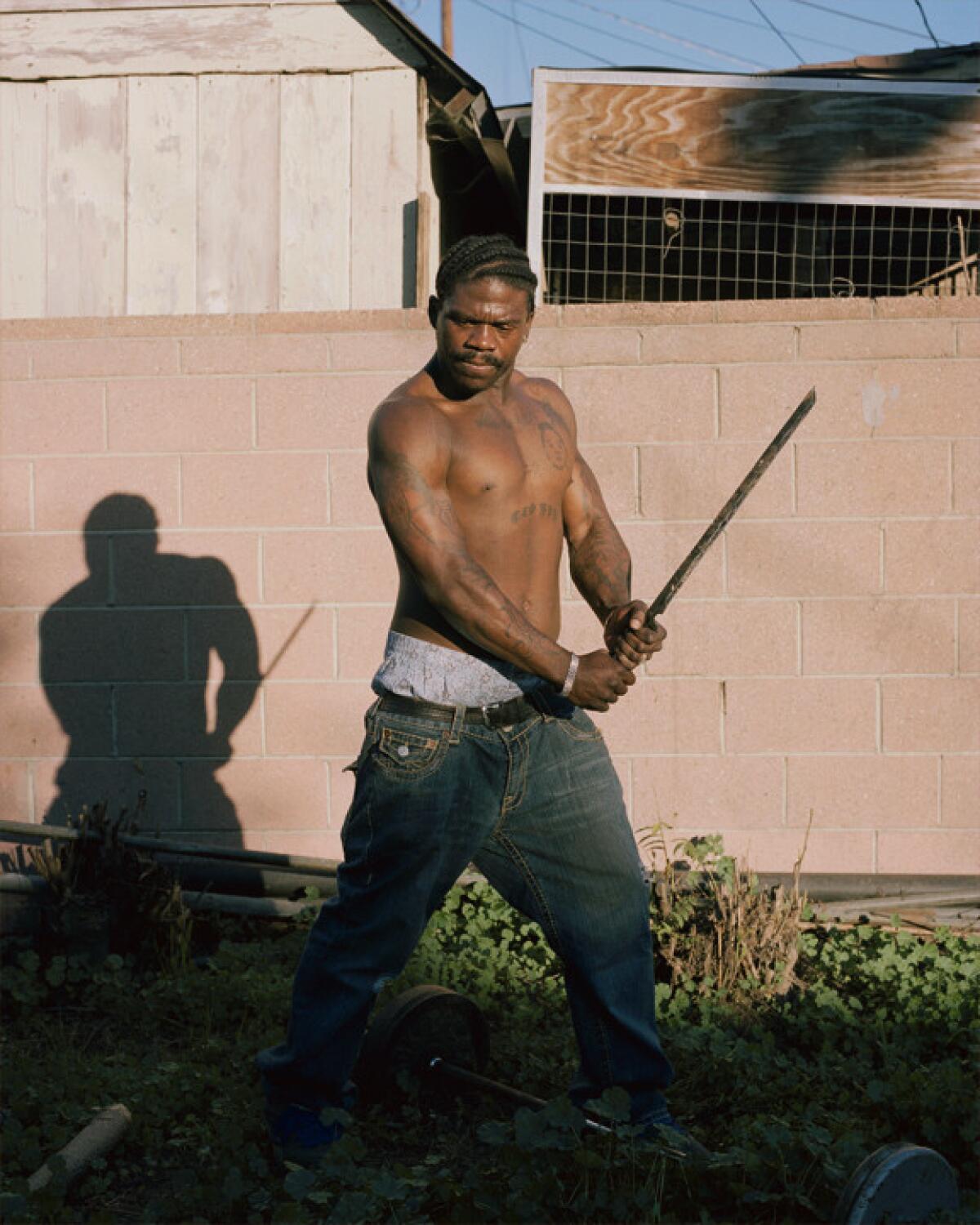

Now a dozen of her large-scale portraits are on view at the Main Museum in downtown Los Angeles through September. “I Dream of Los Angeles,” as the exhibition is called, captures the denizens of the city in meditative moments — individuals who are mostly young, working class, many struggling to hold onto their dreams in the face of poverty and crime.

The artist, who studied at New York’s School of Visual Arts after her initial photography classes at East Los Angeles College, says photography helped save her from a life on the streets. “When I pick up a camera, it’s right,” she says. “It always has been.”

In this lightly edited interview, Montana describes how she finds her subjects, her sources of inspiration and the lens through which she sees Los Angeles and its people.

How do you choose your subjects?

In the beginning, they kind of came to me. The first two subjects [in this series] were Felipe and Mayra. Felipe came to me. I was photographing on Indiana [Street in Boyle Heights] where there is that famous pine tree [El Pino] — doing random landscapes as a palette cleanser. He saw that I had this big camera and he started talking about the landscape of the area and when he came from Mexico as a very young child. I don’t speak Spanish very well, but it didn’t matter. He just wanted to tell me his story.

I saw that he kept making eye contact with the camera and I asked if I could photograph him and he said, “Sí.” And I got the camera, took a picture and did another exposure with different light — and that was it. Then he turned and walked away.

I want people to understand the narrative of Boyle Heights. ... I’m interested in, who is this place?

— Star Montana, artist

With Mayra, she was a friend of one of my best friends. She was walking down the street. It was magic hour in winter. She was telling us this story about how she almost died twice in a week — a gang of girls had jumped her and beat her up. She has a black eye. She is telling this story and the light is hitting her and I’m looking up at her and I think she looks so powerful. And I said, “Wait!” And I ran across the street and I got my camera.

We did more photographs, but then it changed because she got nervous.

What aspect of Los Angeles are you trying to capture in your work?

It’s important, the name of it, “I Dream of Los Angeles.” It’s my idea of Los Angeles. Because I grew up in Boyle Heights, I want people to understand the narrative of Boyle Heights. A lot of these people, they are trying to navigate how to exist in these neighborhoods. These people represent communities and neighborhoods. They exist. And they are individuals. And their stories — each one of them — their narrative is important, too. It’s important for me to sit down with them, even if it’s just for a minute.

I’m interested in the interview. I’m interested in the individual person. I’m interested in, who is this place?

Each portrait is accompanied by very personal texts describing your relationship to the subject or your feelings about their circumstances. Why is that important for you to include?

I always have lengthy descriptions with all my work. It’s about narrative. I’m very transparent with that — who I am as an artist, who I am as a person. It’s about how I make work and how I interact with people. It’s about people and who they are. I come from a very painful past and when people tell me their narratives, how they feel that they don’t exist or how they’ve been marginalized — I come from where they come from and I understand. And I tell them I understand.

An image is skin deep, so it’s about understanding the context of that image. Plus, I love reading. I’m a big book nerd. Words and text are as important as imagery to me. With all of my work, it will always be like that.

In these texts, you also discuss the circumstances of some third- and fourth-generation Chicanos — and how their circumstances differ from the immigrant generation. You explore this idea of America’s promise not being kept.

That’s a big part of my work. I’m fourth-generation Mexican American. My father was an immigrant, but I don’t know my father. My mom would say, “We’re Americans.” We got raised through assimilation. The idea of the promise not being kept — a lot of my studies are about exploring this. My great grandparents, they are from Chihuahua [in Mexico]. They had most of their children in El Paso and then they brought them here. All of their children were raised in the L.A. Unified School District during assimilation.

What I’m talking about, is that the people that are third- and fourth-generation, they thought if they could assimilate, they could transcend class and race and be able to pass. Some people are able to and some people are not. A lot of my mom’s cousins, they tried to achieve the American dream and become middle class, but it didn’t happen. Many went to Vietnam because they didn’t go to college. They came back heroin addicts.

So how do you deal with the American dream when you’re fourth generation and you’ve watched a lot of people die?

How did your life change when you began to study photography at East Los Angeles College?

I started taking classes at ELAC at 16. I failed my first photo class. I would take street-life portraits and my professor wanted me to be a product photographer. I don’t think he understood it. But I took the class again. I was using a camera I found at a swap meet: 35mm, black and white. You learned how to process your film. You printed your pictures. It was very technical. And it kept me away from the streets. I’d photograph my friends and then I was like, “Peace! I gotta develop this roll for three hours.”

I come from where they come from and I understand.

— Star Montana, artist

Your family has played a prominent role in your work. How do they feel about it?

My friends and my family, they enjoyed it because they were visible. They were like, “Hey, do you have film? Come photograph me!” They wanted to be visible. My cousin — I would photograph gang life. I wasn’t glamorizing it. It was a way to document it. I was learning my craft.

But at 19 my cousin got brutally murdered on Cesar Chavez Avenue. Everything changed. He was like my twin. I didn’t shoot black and white again and I’ve never shot street life again.

Who are the photographers you look to for inspiration?

Joseph Rodriguez is probably my favorite. I was 16 and Google was so basic and I put in “East L.A. photographer” and I found him online. I just knew, it felt authentic. [His series] “Eastside Stories,” which documents L.A. gang life in the ’90s — when my cousin was alive. He’s always lived in New York, but he lived in L.A. to make the work. There was something so authentic about Joe’s work. He’s my mentor now.

What is your dream shoot?

I think I would love to go cross-country and photograph brown people, black people, marginalized areas — getting more people’s stories. I know what it’s like to come from a place that is forgotten. Boyle Heights was forgotten for a very long time.

“Star Montana: I Dream of Los Angeles”

Where: The Main Museum, 114th W. Fourth St., downtown Los Angeles

When: Through Sept. 24

Info: themainmuseum.org

Sign up for our weekly Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

ALSO

The last (porn) picture shows: Once dotted with dozens of adult cinemas, L.A. now has only two

Look what happens when you interview artist and Instagram sensation Guadalupe Rosales via text image

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.