Culinary Icon: Chef Jeff Jackson helped bring the farm to San Diego’s table

One in an occasional series on San Diego’s dining icons.

Chef Jeff Jackson was raised in Oklahoma City on canned vegetables and frozen dinners.

Not quite the culinary backstory you’d expect from one of the pioneers of San Diego’s farm-to-table movement, whose restaurant — A.R. Valentien at The Lodge of Torrey Pines — is nationally renowned for its faithful devotion to everything fresh, local and seasonal.

But that’s what America ate back in the 1950s and ’60s. It was modern, it was convenient and it was how busy housewives got dinner done.

And Jackson’s mom was busy — with five kids, a husband who was a traveling salesman for General Mills and piles of sewing, laundry and den mother responsibilities to tackle.

“She kept us alive. There was always food on the table, but I can remember the rotation. It was always the same,” Jackson said, with a laugh.

“It’s not like I have any nightmares about meals, but it’s not like I was raised by Julia Child. We weren’t doing duck à l’orange on Saturday night.”

Though Jackson is trained in classical French cooking, you won’t find duck à l’orange on the menu at A.R. Valentien either. But you will find “chicken under a brick,” a customer favorite since the restaurant opened in 2002. It’s the kind of dish that epitomizes the 61-year-old chef’s authentic approach to cooking.

“It’s just roasted chicken with braised greens — super, super simple. But good,” he said.

As with any artisan craftsman, Jackson said, “the materials in cooking is what makes or breaks you. You can attain the best results with the best ingredients. Simplicity is the key. You take a simple approach to the preparation and the presentation and you let the ingredients speak for themselves. It’s the most difficult kind of cooking — there’s nothing you can hide behind.”

As one of the founding fathers of the local farm-to-table movement, Jackson has had a defining role in helping transform San Diego dining culture, perhaps most notably by formalizing the inextricable link between chefs and farmers through his annual Celebrate the Craft festival.

Among his fellow chefs, Jackson’s steadfast dedication to fresh, seasonal cooking isn’t empty marketing.

On a recent shopping trip to the Little Italy Wednesday Market, Jason McLeod, executive chef of Born & Raised and Ironside Fish & Oyster, pointed to a row of farm stands.

“Jeff Jackson has been doing this quietly, under the radar, for years,” McLeod said. “Some chefs you’ll see on Instagram posing with a farmer or a fisherman and you know he doesn’t buy his stuff there. With Jeff, there’s no Facebook, no Instagram, no picture with a farmer. He just does it.”

As part of an occasional series on the culinary icons who make up an essential part San Diego’s dining DNA, we spoke to Jackson about screaming chefs, the phrase that makes him cringe and the most famous waiter he’s ever had.

Catching the bug

As a kid, Jackson was hyperactive. “I couldn’t stop moving. Today, I’d probably be diagnosed with ADHD,” he said. His parents put him in football to blow some of that energy off — and to get him out of the house — and he juggled multiple jobs in high school. He started working in restaurants at 13, bussing tables, washing dishes and gradually began helping out the cooks. “I kind of got bit by the bug. It’s the classic way to move up the ladder — doing dishes, then peeling potatoes, then peeling carrots.”

Getting schooled

After high school, here’s what Jackson knew: He equated going to college with getting a desk job. He couldn’t handle sitting at a desk job. And he wanted to cook. He knew the Culinary Institute of America was the best cooking school in America, so he enrolled. Here’s what he didn’t know: anything about food. “I had no clue. I’d come from the land of Green Giant green beans in a can and frozen dinners. All of a sudden, I’m learning about chicken stock and consomé,” he said.

‘The greatest advice I ever got’

Jackson’s “yes, chef” light bulb went off as soon as he got to the CIA and an instructor asked, “who here is going to be a chef after graduation?” Everybody in the class raised their hand. Wrong. None of them. “He called us on our (B.S.),” Jackson said. “He said, ‘before you can be a chef, you need to find the best chefs you can work for, learn from them, watch them, let them teach you everything they can. Don’t worry about the money, then go the next chef and learn from the best. … You’ve got to learn the craft.’ That was the greatest advice I ever got. It was the worth the price of tuition for two years.”

Learning the craft

After graduation, Jackson — not yet a chef — heeded that advice and went to work for French master chef Jean LaFont, who was called a giant of Dallas fine dining. It was the late ’70s-early ’80s, the era of nouvelle cuisine — which broke away from, lightened up and simplified traditional French cooking. LaFont was part of the famous circle of nouvelle chefs that included the legends Paul Bocuse and brothers Jean and Pierre Troisgros. The experience was transforming and also got him in the door of Chicago’s Le Francais under chef Jean Banchet, who the Chicago Tribune said “almost single-handedly raised Chicago’s dining reputation from a steak-and-potatoes town to a serious restaurant city.” Jackson said “two years there were like getting a post-graduate degree from Harvard.”

What not to do

The budding chef thrived in Banchet’s kitchen, where he was taught more than how to perfect the mother sauces. “I learned what passion was,” Jackson said. “Things had to be perfect and if it wasn’t, he screamed. He was a screamer. … I need to be in an environment with a task master. I need to be told I can’t do something, so I can then do it. I take it as a challenge. Screaming was the old way of doing it. … I made a conscious decision when I left the kitchen at Le Francais that I would not be like that.”

Garçon!

Among the towering figures of French chefs in the U.S., perhaps none was bigger than André Soltner. His famed Manhattan restaurant Lutèce “for decades … set the standard for fine French cuisine in this country,” said The Daily Meal in its 2016 Hall of Fame induction of Soltner. “No less an authority than Julia Child considered it the best French restaurant in America.” One night, Jackson made a pilgrimage to Lutèce. He remembers the white asparagus and the Dover sole. “It was a life-changer,” he said. Also memorable: his server. “André Soltner came out and took our order. We had an early reservation — it was the only time we could get — and I don’t know where the waiters were. It blew my mind.”

Selling out?

Moving on to the Park Hyatt in Chicago, Jackson was making his own critically acclaimed name for himself, first as the executive sous chef at the signature restaurant La Tour and next as the executive chef for the whole hotel. Then he won the Bocuse d’Or USA championship and represented the U.S. at the world Bocuse competition — the Olympics of cooking — in Lyon, France, in 1989. Catching the attention of the group opening Shutters on the Beach in Santa Monica, Jackson was wooed with a job at the soon-to-become quintessential L.A.-area luxury resort. As a chef with ambition and the skills to back it up, Jackson was hesitant. “Back in those days, the thought of going to California for a chef in New York or Chicago was considered a sellout. There was no credibility.”

The bounty breakthrough

What California did have, Jackson, soon found, was an unparalleled year-round variety of fresh, high-quality, produce, seafood, meats, diary products and other ingredients chefs elsewhere crave. He began shopping at the Santa Monica farmers market and developed relationships with farmers, some of which still exist today. “That was an eye-opener,” he said. “Santa Monica is where the whole idea for Celebrate the Craft came from.”

Landing at the Lodge

After 10 years at Shutters, Jackson, a married father of two, was put in touch with Bill Evans, who was opening The Lodge at Torrey Pines, a luxury, Craftsman-inspired resort overlooking the Pacific and the famed golf course. “We spent five minutes with each other and we said, ‘Let’s do it.’ ” Evans, whom Jackson called “the best boss I’ve ever had,” was taken by the chef’s passionate case for using the highest-quality ingredients and the parallels of Craftsman cooking and architecture. “He has given me the latitude and respect and the environment to give me the creativity to do what I do best,” Jackson said.

Farm to (only a couple of) tables

In the early 2000s, Jackson said, there was a small cadre of chefs — Jack Fisher, Carl Schroeder, Trey Foshee and Michael Stebner, who, along with Fisher, opened Region in Hillcrest, the pioneering farm-to-table restaurant — truly cooking seasonally. “They were the only ones in this town using farms,” he said. Stebner was the only one going out to the farmers markets, meeting local farmers. He would drive to Jamul, to Julian. He was the only one to do that.”

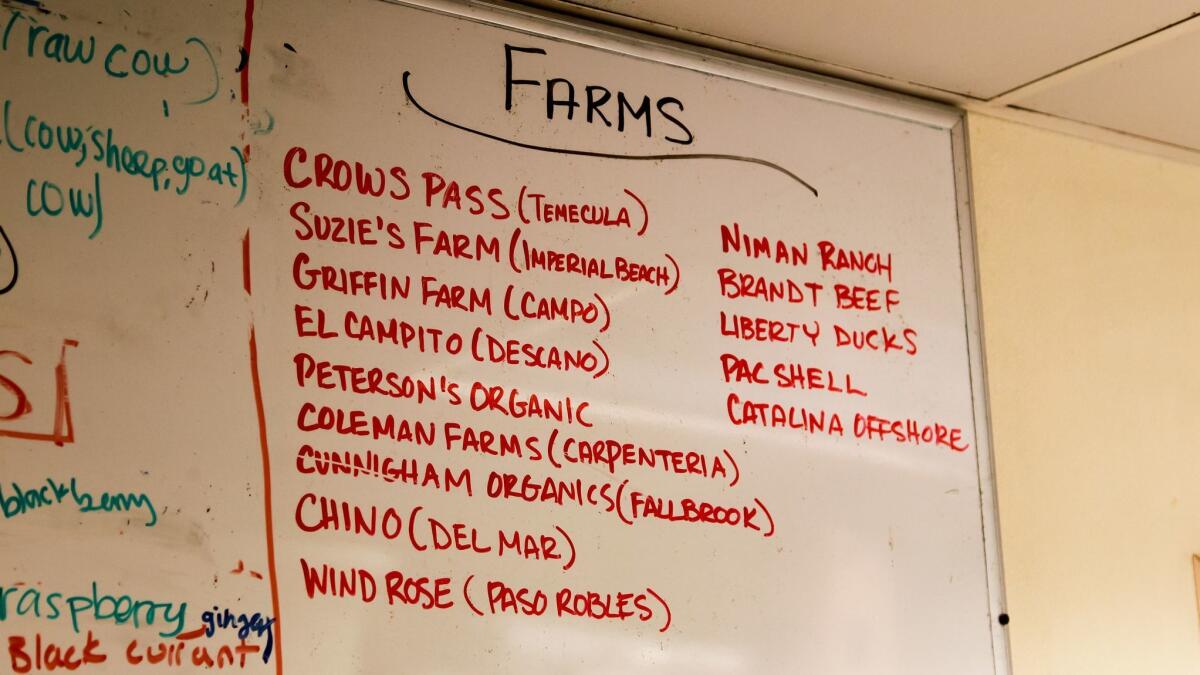

Building a community

Jackson wanted to change that, so he founded Celebrate the Craft, now in its 16th year. While a hit with restaurant-goers (about 50 percent of attendees come each year), “I wanted to introduce San Diego chefs to the farmers I had used in Santa Monica … who came directly with their trucks full of produce.” Jackson paired each participating chef with a farmer and a winery. “The whole idea was to turn chefs on to the farmers. … And along the way, it educated the public as well.” He’s proud to have Celebrate the Craft as part of his legacy. “Being one of the people that was able to build this culinary community is probably the thing that I’m most proud of.”

‘I hate it’

At the elegant, civilized A.R. Valentien, entrées come with vegetables for the table, which Jackson said is a way to showcase local produce. The restaurant’s monthly Artisan Table series, featuring wineries and guest chefs, is centered on “sharing a communal meal of seasonal bounty.” But Jackson admits that the phrase “farm-to-table” has become so overused that it makes him cringe. “I hate it,” he said. “There are quote-unquote organic farms. There are heirloom tomatoes at Ralphs and Vons that have no taste. Just because it says heirloom tomato doesn’t make it a good tomato. … There are chain restaurants using it. When Carl’s Jr. starts using farm-to-table, when that happens, it’s time to come up with a new catchphrase.”

Standards, not screams

At an Artisan Table dinner earlier this year, Jackson’s former chef de cuisine T.K Kolanko, now executive chef of Blue Bridge Hospitality, was the guest chef, preparing dishes inspired by a trip to Asia. Another former chef de cuisine, Kara Snyder, of Tender Greens, came to show her support. The two chatted with current chef de cuisine Kelli Crosson and realized they had each worked for Jackson for at least 10 years — which, in an industry known for burning through employees, says something. And for the record, they wanted it known that Jackson was most definitely not a screamer. “People think he’s tough but it’s more that you don’t want to disappoint him,” Snyder said. “It pains him if you do something wrong. He’ll be like, ‘Dude, how could you do that?’ ”

A.R. Valentien

Address: At The Lodge of Torrey Pines, 11480 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla

Phone: (858) 777-6635

Online: lodgetorreypines.com/ar-valentien

Coming up

Artisan Table Guest Chef Series, featuring a Japanese and sake theme prepared by chefs Shihomi Borillo and Andrew Spurgin. 7 p.m. Aug. 9. Tickets: $165.

michele.parente@sduniontribune.com

Twitter: @sdeditgirl

Sign up for the Pacific Insider newsletter

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Pacific San Diego.