TV’s tainted heroes don’t have to be a hard sell if given enough humanity

A couple years ago, fresh from their shared ascent into the television pantheon with “Breaking Bad,” three graduates of that show’s epochal five-year run met in the garden of West Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont. Show creator Vince Gilligan, his colleague and right-hand writer Peter Gould and actor Bob Odenkirk were there to discuss whether Odenkirk’s morally bankrupt but irresistibly amusing shyster lawyer character from the show, Saul Goodman, could have a second life. “At the time,” says Odenkirk, “they weren’t sure. A half-hour comedy was even considered. But my first question was, ‘How do we make him a likable enough guy to be the protagonist of a series?’”

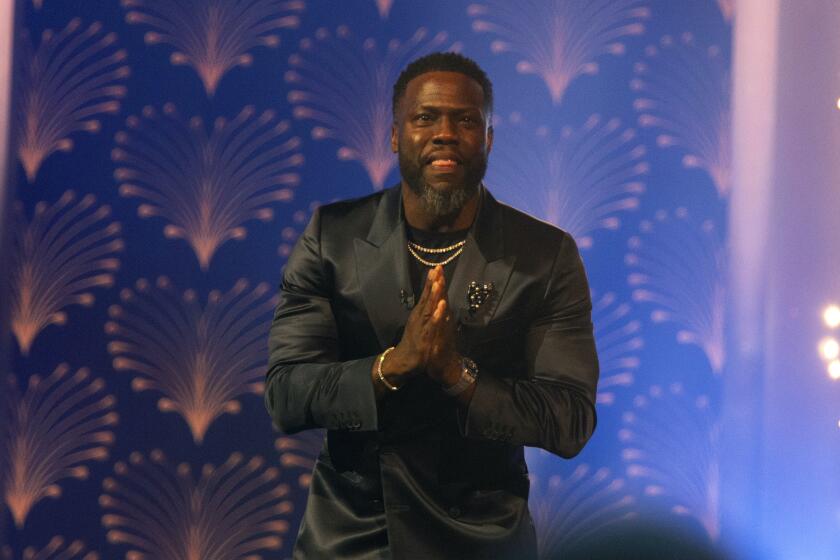

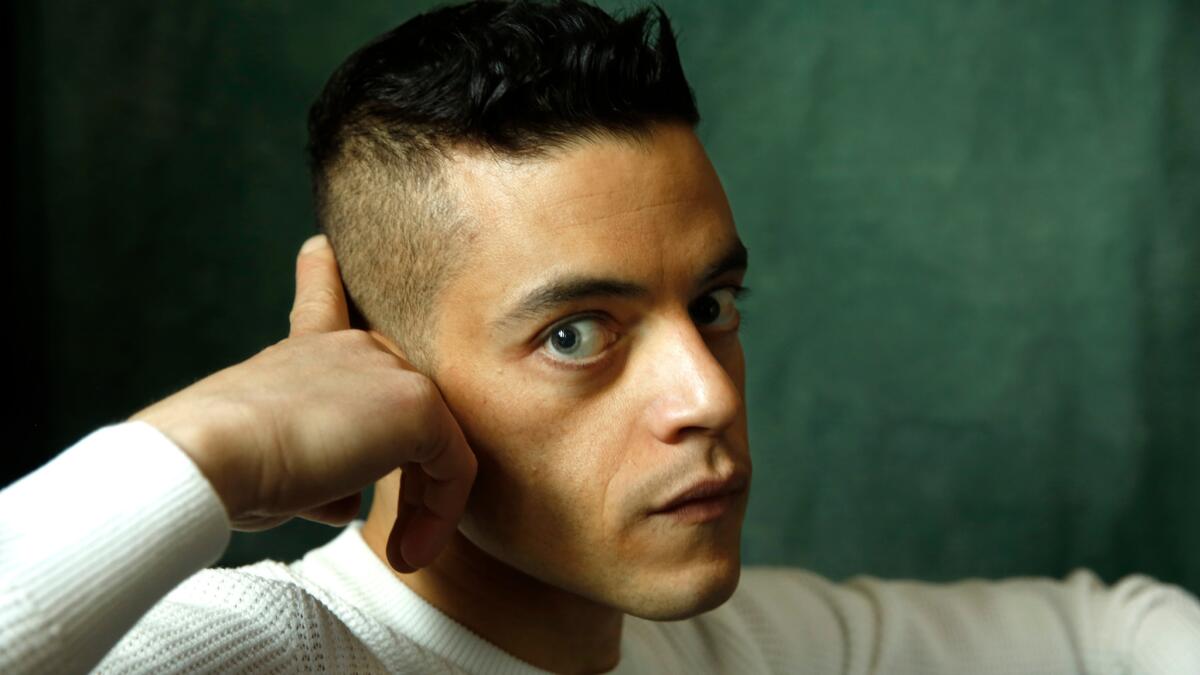

Odenkirk’s recent second Emmy nomination for “Better Call Saul” assures us a solution did arrive, but the quandary they initially faced is one each of his fellow lead actor in a drama nominees would also seek to solve: How do you take a dark-hued protagonist and convince audiences to follow him? Rami Malek’s troubled hacker Elliot in “Mr. Robot,” Matthew Rhys’ agonized Russian spy Phillip on “The Americans,” Liev Schreiber’s bat-wielding Hollywood fixer in “Ray Donovan,” Kyle Chandler’s fratricidal cop John Rayburn in “Bloodline” and Kevin Spacey’s sinister “House of Cards” politician Frank Underwood all come with something of a toxic aftertaste.

“Saul’s” creators felt sure they could establish a sympathetic rogue in Jimmy McGill, a lawyer who’d later change his name to Saul. “Our great concern was, where is this character’s vulnerability?” recalls Gould, “How can he be hurt? If he has nothing to lose, you miss the humanity.” By giving Jimmy compulsive brother Chuck (Michael McKean) and wised-up girlfriend Kim (Rhea Seehorn). “Learning he cares so much about them helped us find that character,” says Gould. Adds Odenkirk, “You can’t help but enjoy Jimmy’s exuberance, even as it’s married to his bad ideas.”

Schreiber’s Ray worked the seams of corrupt Hollywood for most of four seasons before he showed his abuse-damaged innermost self in a teary confessional with a priest, soon followed by a surprising one-line benediction to his troubled family. “I knew what I had to say was, ‘I love you all so much,’ but those words are uncommon to Ray, so something had to break, he had to let go and be vulnerable — and that’s the most terrifying thing in the world for him,” the actor says. To “Ray” show runner David Hollander, “What makes a heroic character today is the examination of the flaws. What all good stories are doing is examining the truth of being a modern human being compelled by many different desires — to love a family, to be married, be lustful, to have money or not, wanting to serve others or not.”

Rhys stepped in to direct this past season’s episode of “The Americans” in which his character must cut loose a pretend wife he’s exploited for spy work — a scene he and writer Stephen Schiff agreed should play without music, and with only one last line from the heartbroken woman: “Don’t be alone.” To Rhys, “there’s nothing you can say to another human being at that point that will in any way balm what’s going on, nor his own great guilt.” He adds, “I never play for the audience’s sympathy — they know the toll it’s taking. It makes him and Elizabeth [costar Keri Russell] real, in that they are fallible. I love this character not as a spy who can do everything, but for the cracks and chinks.” To Schiff, the characters’ agonies highlight “the division between what someone does and what someone is. In wrestling with that division, we recognize there’s something molten and juicy and complex.”

“Bloodline” co-creator Daniel Zelman knew in casting Kyle Chandler, formerly “Friday Night Lights’” embraceable Coach Taylor, “People would lean into Kyle, who we learn does this unthinkable thing. We watch him struggle to do the right thing, but even when a family gets rid of the black sheep, you actually don’t get rid of the problems — they just move around.”

“Mr. Robot’s” Malek agreed with show runner Sam Esmail early on that his addictive, closed-off character “was not your average human being. We never aspired to make him likable. He has certain aspirations for the way he would like the world to be, and he was gonna go after that any way he could.” As the low-affect Elliot gradually exhumes his past, says Malek, “You’re forced as an audience member to navigate inside his head, see everything he’s grappled with that becomes that much more telling.”

Perhaps “House of Cards’” Spacey most dares us to withdraw, as the patently evil POTUS who steadily proves, as he says, “This ain’t your daddy’s West Wing.” Not unlike Malek’s Elliot, he turns to the audience with barbed commentary. “I like to think of the direct address as [talking with] your best friend — the person you tell things you wouldn’t even tell your wife.”

In the end, it’s these glimpses of humanity and vulnerability that keep viewers coming back for more of these compelling, yet tainted, heroes.

calendar@latimes.com

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.