‘All Is Lost,’ ‘Gravity,’ ‘Nebraska’ go big with small casts

At some point during the filming of “All Is Lost,” writer-director J.C. Chandor and his star (and sole cast member) Robert Redford were getting a little sick of one another. As the only actor on set, Redford had no one to commune with beyond the crew, and Chandor had been staring at him through a lens for weeks.

“He got unbelievably fed up and bored with me,” Chandor says. “It’s sacrilege to say it, but you start to feel the same way about him because the two of you are just staring at each other day after day with no one to talk to.”

Over the years, much has been made of movies that tout “a cast of thousands” — from D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation” to the many ensemble comedies from Garry Marshall. But, more recently, directors have been focusing their lenses on far fewer performers. Consider the largely solo work by Tom Hanks in “Cast Away” in 2000 and newcomer Suraj Sharma in last year’s “Life of Pi.”

PHOTOS: Behind the scenes of movies and TV

That is increasingly true this award season as many of the buzzed-about films have stripped down their visions to their cores — “All Is Lost,” “Gravity” and even this weekend’s road-trip movie “Nebraska” to a degree — featuring tiny casts and limited dialogue. All three films, in one way or the other, appear to be trying to re-create an increasingly rare intimacy with audiences that have become used to being overwhelmed with spectacle.

Such intimacy was Jonás Cuarón’s goal in writing “Gravity” with his father, Alfonso, who also directed the film about two marooned astronauts, played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. “We believed when you stripped a story down to such basic elements, you could make a connection with the audience,” the younger Cuarón says. “We wanted it to be this immersive experience, so at the end of 90 minutes the audience will have gone through the same emotional journey as [Bullock].”

Chandor agrees it is about the audience’s journey. “I want you to come into the movie,” he says about “All Is Lost,” in which Redford’s unnamed sailor is stranded adrift on the ocean. “For the people the film works for, they have this intense personal relationship [with Redford’s character]. Within a survival genre, the audience has to fully feel why he’s fighting so hard to live.”

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

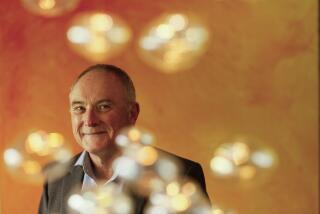

With “Nebraska,” director Alexander Payne had a larger cast, but much of the movie centers on just two characters: a father and son (Bruce Dern and Will Forte), with some long sequences in a car in which the two barely speak. For writer Bob Nelson, that was a terrific chance to build character.

“There’s so much talking in American movies; everyone’s afraid to have any kind of quiet,” Nelson says. “The thought was that these two would not have much to say to each other at this point. It’s important for the audience to try and read the actors — not have what they’re thinking spelled out in exposition.”

Yet there are unusual problems in making a film with casts in the single digits. Jonás Cuarón struggled to create a character who was “so engaging the audience would really invest in her” and felt relieved when Bullock and Clooney made it work. “From the beginning, they understood where we wanted to go with the story, so it was all organic,” he said.

Payne had to use his considerable skills to keep that long “Nebraska” sequence in the car interesting. “It’s a balance of knowing when performance alone is carrying the day and when a shot is overstaying its welcome,” he says, noting for example that the famous scene with Marlon Brando and Rod Steiger in “On the Waterfront,” shot in the back of a car, is “the most standard shot in the world, but you can’t take your eyes off of it.”

VIDEO: Interviews with the cast and crew of ‘Nebraska’

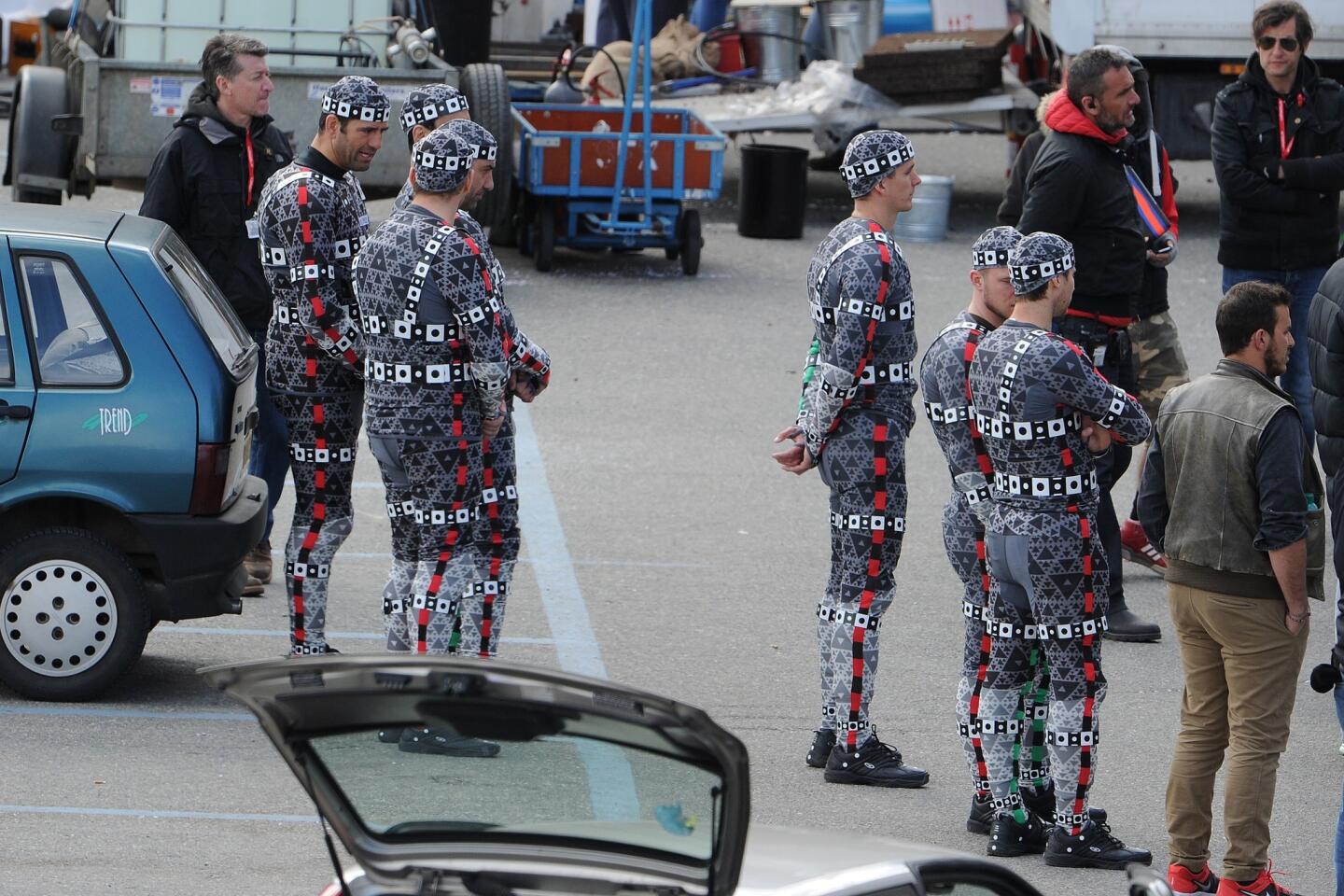

The real challenge for Chandor came in post-production. “Editing a one-person movie — it was not very much fun,” he says. Transitions were technically difficult and, in the end, nearly every action in the film was a jump cut. “I will never go through anything like that again.”

Still, for all these directors, the use of the small cast felt like a way to revisit what it meant to be immersed in a movie in a traditional theater. The overwhelming size of the screen, used to convey the plight of just one or two people, Chandor says, harks back to the early days of film.

“All of these films you’re seeing this season, they’re meant to be experienced communally,” he says, “with a big old screen and a big old sound system that brings you into another world, so you can’t also be looking at your phone.”

But there was a lesson to be learned, at least for the Cuaróns. While Jonás Cuarón’s next film will also be a small-cast story (two characters on a ride in the desert), he says he and his dad did learn something while making “Gravity”: “Never to make a movie again in zero G,” he says with a chuckle. “Anywhere, so long as they’re not floating.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.