The Player: ‘That Dragon, Cancer’ brings a serious real-life ordeal to gaming

One of the first things you hear in Ryan Green’s video game is a voice mail. Though it’s not a horror game, the sound isn’t just frightening; it’s borderline bone-chilling.

A woman leaving a message for her husband sounds exasperated. She’s leaving the doctor’s office and coming home without any answers. The couple’s baby boy is vomiting. Maybe it’s this? Maybe it’s that? There is no diagnosis. And why is the child’s head always cocked to one side?

Everyone is thinking the worst, but no one is saying it.

At this point the player can see a glimpse of the boy, whose name is Joel. The voice mail, it turns out, was a memory, and Joel, now older, is on a slide in a park. He’s almost 5. His older brother wants to know why he doesn’t talk. Yet Joel still has the ability to bring a smile to people’s faces — and to player’s faces, such as the moment when he tries to feed a duck in a pond by throwing an entire loaf of bread at the animal. Is Joel going to be OK? Just like so often in the real world, the answers may be unclear or unpleasant, but this is not a game about solutions.

This is “That Dragon, Cancer,” an in-development video game that raises the sort of big questions video games have long avoided. The common ones — Is it challenging? Is it fun? — are practically irrelevant here. Green and a small team that includes his wife, Amy, are after something more ambitious. Can a video game teach us something about death? Or, maybe more accurately, can a video game be a memoir?

Even in the vastly expanding world of independent gaming, this is largely untested terrain. One early admirer of “That Dragon, Cancer,” compares it to Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking,” which was written in the aftermath of the death of the author’s husband. Like that novel, “That Dragon, Cancer” copes with loss and heartbreak via wishful thinking, imagining at times an alternate past and future while the outcome stubbornly refuses to change.

Although writing about cancer is relatively common in literature, it’s a rarity in gaming. Discussing the illness — and how it affects

a family whose son was ultimately diagnosed with terminal brain cancer is a major risk in a medium where play is paramount.

Now two years into development, Green and his team have turned to the crowd-funding site Kickstarter in the hopes of keeping the project independent. At the time of writing, with three weeks left to secure funds, “That Dragon, Cancer” has raised just shy of $60,000 of its $85,000 goal.

The game is in development for PCs and Macs, and Green has also been working closely with Ouya, an independent publisher and home console maker. There’s even a documentary in the works, “Thank You for Playing,” which filmmakers David Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall intend to bring to film festivals in 2015.

“That Dragon, Cancer,” says Osit, seems “like a special way to approach the unapproachable.”

‘Give us a shot’

But making people curious isn’t the same as making them want to play, and Green knows his game can’t make players uncomfortable — well, too uncomfortable.

“I would love it if people are willing to trust us, to go there with us,” Green says. “We’re not trying to hurt you. Give us a shot. But there are certain movies I haven’t watched on purpose because it’s a kid with cancer. I know I’m asking a lot of people.”

The game has shifted direction over the last two years, in no small part because Joel, Green’s real-life son who inspired “That Dragon, Cancer,” succumbed to the illness in March at age 5. Some of the earliest scenes created for the game were its most harrowing — moments in the hospital where Joel can’t stop crying and internal monologues of Ryan and Amy that captured the instant they first learned their son was terminal.

“It had a bleak edge,” Green says. “Creatively, it’s easy to go there, but I was insisting that this be a hopeful game.”

An abstract touch

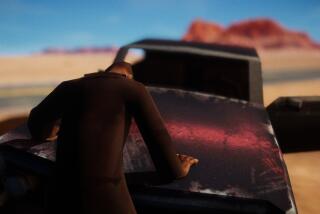

After Joel’s death, the tone began to change. New scenes are more abstract. With an art style that focuses on bold colors with a papier-mâché sort of feel, “That Dragon, Cancer” is not striving for realism.

At the same time, the hospital scenes focus less on the disease and more on its real, emotional toll — the guilt a parent feels at wanting to sleep, for example. There is no scene, for instance, in which players will see Joel in pain.

“I’m not interested in showing a child suffering,” he continues. “Anytime we show kind of hard things, we do it in a metaphorical or symbolic way. When Joel used to be upset, he would bang his head on things. I’m not interested in showing that. That was awful enough to experience. I think there’s certain ways we have to pull punches.”

Though individual play experiences will ultimately vary, “That Dragon, Cancer” will serve a purpose that the Greens may not have intended. When completed, the project will offer yet more evidence that video games are now a valid space to explore all facets of the human experience.

“This is a personal experience for us, but there are thousands and thousands of families who go through this,” Green says. “This is universal.”

That’s not a claim many games can make.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.