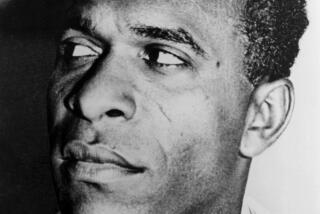

Book review: ‘The Cross of Redemption’ by James Baldwin, edited by Randall Kenan

The Cross of Redemption

Uncollected Writings

James Baldwin, edited by Randall Kenan

Pantheon: 308 pp. $26.95

Not infrequently, James Baldwin found himself quite publicly fielding a deeply presuming question. Though versions varied over time, the rough paraphrase was this: “Was being born black, gay and poor a ‘burden’?” Did he ever wonder, “Why me?”

A dynamic, trailblazing presence on erudite TV chat shows as well as a de facto talking head booked to parse the complex territory of the Negro Problem, Baldwin was always ready with the not-so-inscrutable smile, then the ice-water answer: “No. I thought I’d hit the jackpot.”

It’s typical Baldwin — catching the questioner off-guard, turning the assumption on its head. And while, of course, it is a fine riposte, reexamined it isn’t entirely accurate.

We hit the jackpot — all of us — anyone interested in engaging in candid albeit stakes-changing debate, anyone who had an investment in equity, humanity and its future. We gained tremendously from the variegated prism through which he viewed and translated the world.

From the late 1940s until his death in 1987, Baldwinwalked into the very center of the maelstrom — whether it was the rhetorical theater of debate or the very front line of violence of the Jim Crow South — but he wasn’t simply everywhere at once: He was deeply invested in each and every outcome.

Not often have we felt what it might have been for Baldwin. A cultural omnivore, he was often called on to sort through and interpret the impossible. “The Cross of Redemption,” an expansive new volume edited by Randall Kenan, brings together a diverse sampling of Baldwin’s words in the form of speeches, book reviews, lectures, letters, magazine profiles and essays. These pieces, previously uncollected, not only give us a sense of the physical distances he traveled to “bear witness” but the intellectual latitude he stretched.

Kenan’s collection showcases this Baldwin — the public intellectual, before the term was tossed around so unreservedly. And though he was often called upon to work through the complex algebra of America and its “race problem” — what this volume underscores is Baldwin’s immense cross-disciplinary range — as a reader, thinker, lecturer and pundit. Though race was a theme that was never out of arm’s reach, his preoccupation with societal ethics and humanity was tantamount. And though, as Kenan points out in his evocative introduction, Baldwin first and foremost considered himself a novelist, it was the essays-particularly “The Fire Next Time” and “Notes of a Native Son” that cemented his fate, which “transformed Baldwin into something more than a writer for the American public and world at large — if the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was the civil rights movement’s Moses, James Baldwin had become its Jeremiah, despite his protestations of speaking for no one but himself.”

Political was personal — and vice versa. Baldwin was on a perpetual journey — speaking, touring widely, granting interviews by day; stealing a few hours at night to write trenchantly about events often occurring half a world away. He was inevitably called upon to perform triage — post-front-page tragedy (assassinations, race hate crimes), post-civic unrest — to distill, contextualize or simply react. What Kenan’s anthology illuminates is the burden Baldwin must have carried. How did he keep it all so balanced? So clear?

He accepted his responsibility with aplomb — his ubiquitous, waved cigarette, his sharply knotted ascot — but his nerves were raw; it was all there, just beneath the surface. The job was great, and time was short: “I’m tired of not only being told to wait, but of people saying ‘What should I do?’ .… One is not attempting to save twenty-two million people. One is attempting to save an entire civilization and the price of that is high. The price for that is to understand oneself.”

Baldwin spent his lifetime bent to this task — coaxing reason out of the iniquitous. As Kenan points out in his introduction, Baldwin seems to have sprung fully formed. A child preacher who’d left the pulpit by age 17 and by “23 so much of the James Baldwin the world will come to admire and heed and laud and consider as indispensable was already well formed.”

Kenan arranges those many Baldwins — the public intellectual, the novelist, the journalist, the activist, the out-of-the-pulpit preacher, side by side. We begin to understand his seamless range: the many Baldwins the world demanded that he be and, in turn, the many demands he had of the world.

Language — written and spoken — was his blade, and it was his balm. “We live in a country in which words are mostly used to cover the sleeper, not to wake him up,” he writes in a 1962 essay, “As Much Truth as One Can Bear.” He wanted to force the uncomfortable topic , to keep the country “awake,” we’d been dozing too long, the hour was late. We know Baldwin for his allusions (“my dungeon shook”) and his idiomatic echoes (“the price is too great”) as much as for his urgency. Moving through these essays feels like peering through a kaleidoscope. With each turn, the shape, arrangement or intensity of his themes — racism, social parity, education, media manipulation, the role of the writer — might change, but the crucial pieces of argument remain fixed.

We’re accustomed to seeing Baldwin in meta — a burnished expansive text that reflects his synthesized observations, voices, anecdotes. Consequently, this collection works as a sketch book — a sort of staging area of thought for the issues that rise to the top of his mind. . He’s pondering the state of black/Jewish relations in one breath; the hypocrisy he encountered in the church in another. It’s the bill-paying work — book reviews of Maxim Gorky or a novel by Elia Kazan; an indelible dual profile of Sonny Liston and Floyd Patterson, clustered around the novels and think pieces we most remember him for. To pigeonhole him as a “race writer” would be, Kenan points out, “a grave mistake.” He was drawing connections. “It is useful to see,” writes Kenan, “how, no matter his topic, how often his writing finds some ur-morality upon which to rest, how he always sees matters through a lens of decency. “

These unvarnished assessments of politics and popular culture provide a chambered time capsule of America in mid- to late last century. He cared deeply about democracy’s very heartbeat — and often turned America’s presupposed must-have checklist on its ear.

” Bobby Kennedy recently made me the soul-stirring promise that one day — thirty years if I’m lucky — I can be President too. It never entered this boy’s mind, I suppose — it has not entered the country’s mind yet — that perhaps I wouldn’t want to be.… what really exercises my mind is not this hypothetical day on which some other Negro ‘first’ will become the first Negro president. What I am really curious about is just what kind of country he will be president of?”

Much of the book reflects this same nuanced prescience — as if he knew what would remain on our minds — in politics, the arts and in the realm of social justice, how elusive a destination “fairness” would be. Baldwin’s was a long, arduous journey — out in the world and on the page. And what’s most striking is how he wrote precisely the way he spoke. The serpentine sentences wandered through the thicket of the problem, then out into the light. He took us with him and left these maps. And though it’s tempting, the question shouldn’t be “What would James Baldwin say or do?” He was grooming us to finish that circuitous, complex sentence for ourselves.

George is an L.A.-based journalist and an assistant professor of English at Loyola Marymount University.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.