Janelle Monae in Wondaland

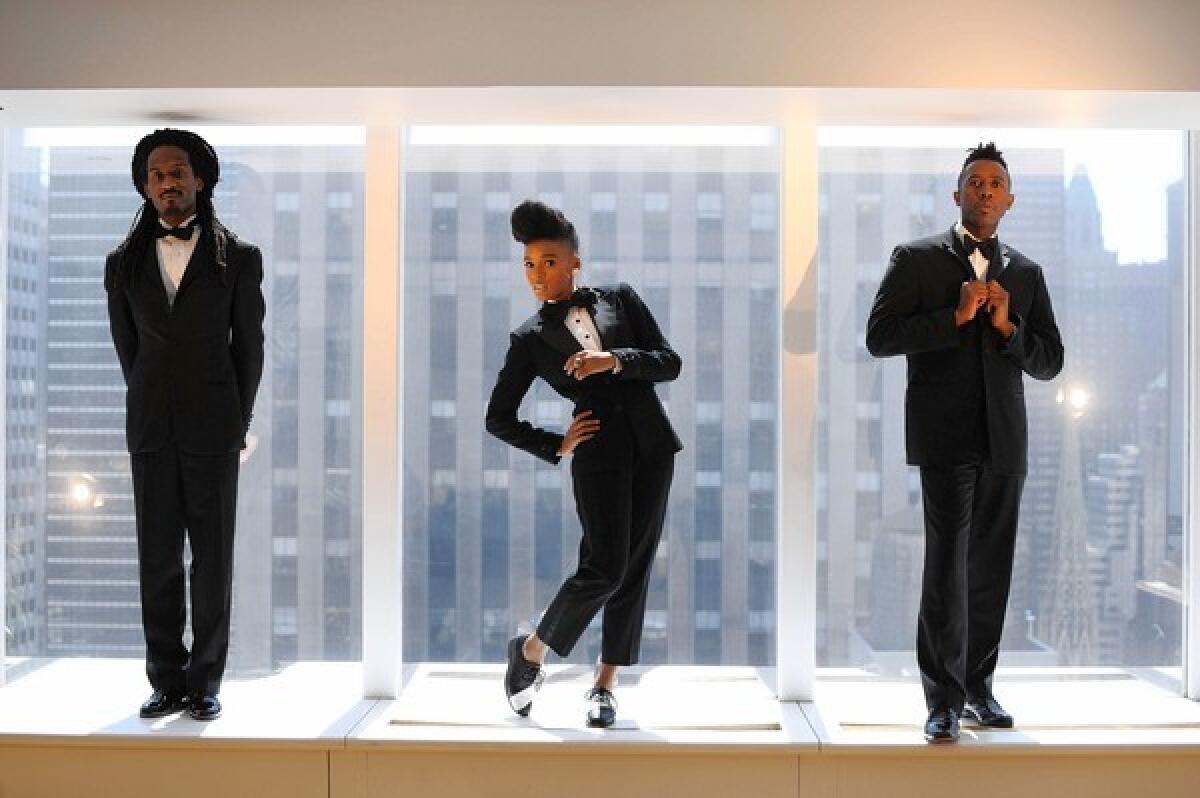

— Janelle Monáe’s feet moved in S curves as her band laid down a backbeat in the converted garage that acts as a music room inside Wondaland, the brick house that serves as her Atlanta headquarters. The singer watched herself in a wall of mirrors as she danced. The sound was sharp and pulled together, like the black and white service industry-style uniforms that each musician wore. This may have been just a rehearsal for an upcoming appearance on “The Mo’Nique Show,” but at Wondaland, everything is a real performance, pursued with grace and forethought.

“This has to be right on,” said Monáe, leading the players through the sizzling James Brown-style fake endings of the song “Tightrope.” “Make sure you hit my cue.” The history of funk bubbled through Kellindo Parker’s guitar parts; you could hear a little Prince, a little Outkast. The melody, like a string let loose and pulled taut again, was Monáe’s own, as were the lyrics about maintaining balance on life’s unpredictable turns. “You can’t get too high! You can’t get too low!” she spit, the look on her face modulating from determination to delight.

As Monáe honed in on her music, the house came alive. Members of the Wondaland Arts Society — Monáe’s chosen artistic family — kept bustling in, past the dozens of Dali-esque clocks on the walls in the hallway (“They’re for the time travelers,” Monáe informed a visitor), past the shelves full of literary theory, business books and novels by Zadie Smith and Junot Díaz, past the television silently playing Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” in the living room.

A team assigned to kitchen duty prepared a feast of skewered meats and veggies and scrumptious barbecued beans. Others held impromptu planning meetings and scanned their laptops, keeping tabs on Monáe’s Twitter feed. It was early May, with just days to go until Monáe’s full-length major-label debut, “The ArchAndroid (Suites II and III),” would be released by Sean “Diddy” Combs’ Bad Boy Entertainment.

The video for “Tightrope,” with Monáe doing her tricky moves with four Memphis-based jook dancers she discovered via the Web, is a YouTube sensation, and she’s gaining raves on the select dates she’s opening for Erykah Badu, a gig that brings her to the Greek Theatre on Sunday.

Both in conversation and in her music, Monáe presents herself as remarkably bold and sure of her vision. Her singing style marries clarity and power in ways that recall greats such as Lena Horne and Dinah Washington, although she’s able to let out a glam-rock wail when the song calls for it. She’s also a talented rapper, with a wickedly precise flow.

“I do think they’re completely capable of having an impact on their generation’s intellectual and pop-cultural life,” said the writer and musician Greg Tate, a longtime mentor to Monáe and her collaborators, “mainly because they’re equally committed to the art, ideas and business aspects of what they do.”

“I’ve always had really big ideas,” said Monáe, who set her sights on Broadway while still in grade school. “I dreamed of writing my own movie and starring in it — all these audacious goals and ideas. Initially, though, I think I loved musical theater more than pop music. I didn’t even have a love of being my own artist. Then once I got in touch with my own ideas, I knew there was some light in me trying to come out.”

It was through co-founding and nurturing the Wondaland Arts Society that Monáe developed that luminosity. The semi-communal group of free-ranging creatives — a dozen or so young writers, musicians, producers, visual artists, video bloggers, dancers, actors and entrepreneurs — is spearheaded by Monáe and her production and writing partners Chuck Lightning and Nate “Rocket” Wonder. The collective is forging new ways to connect hip-hop to other musical genres, literary culture, the performing arts and the World Wide Web.

“I want us to grow into a nurturing place for other artists who have great ideas and music and are brilliant performers, and help expose that to the world,” said Monáe during an interview in Wondaland’s basement recording studio after her rehearsal. “This project is the launch. It will bring the attention and I’ll go out and test the waters for everybody. That’s always been the goal.”

During two days spent watching Wondaland in action, though, there was only one overwhelming focus: “The ArchAndroid.” All involved were promoting it, organizing Monáe’s theatrical live shows, plotting related products such as a graphic novel and Web features, and fleshing out the album’s complicated science-fiction concept. Other projects, including Lightning and Wonder’s group Deep Cotton and a fall tour with indie rock kindred spirits Of Montreal, are slated for the near future. It’s a 21st century endeavor helmed by a historically aware bunch; Lightning connects it to the Harlem Renaissance and Motown, as well as the Black Arts Movement, the cultural wing of 1960s black power.

Lightning was thinking of the Harlem Renaissance when he established a salon called the Dark Tower at Morehouse in 2001. The presenting organization brought artists such as the Roots to campus and supported young hopefuls trying to move outside the slick commercialism of much Southern R&B and hip-hop. Monáe found her way to one of their performance nights and met Lightning and his production partner, Wonder, a multi-instrumentalist who takes the lead behind the studio’s boards.

“My eyes locked with Chuck’s and with Nate’s,” Monáe recalled. “It was a weird energy, not in a negative way. Not in an ‘I wanna date you’ kind of way, but as in, I want to work with you.”

The Wondaland Arts Society came into being as Monáe, Lightning and Wonder turned their attention toward the pop arena. Atlanta’s hip-hop elders, Andre 3000 and Big Boi of Outkast, provided mentorship — “they’re inspired by what the Wondaland Arts Society is doing, and we listen to them,” said Monáe, who appeared on the duo’s 2006 album “Idlewild.” Eventually, Bad Boy label head, Combs got wind of the collective. He signed Monáe after hearing an independent-label version of her first EP, “Metropolis: Suite I (The Chase),” and re-released it soon thereafter in 2007.

“It takes a Puff,” said Wonder. “It takes somebody to be your champion. We know he’ll stand up for us, for our art. And you can’t say that Puff is a small-idea kind of guy.”

Writing from Paris, Combs confirmed Wonder’s view. “The Wondaland Arts Society knows exactly who they are,” he commented. “I know once people see her perform, and hear her sing live, they ‘get it.’ … I respect what they are doing and just want the world to see it. She doesn’t conform to any particular genre, and that’s what I love about her.”

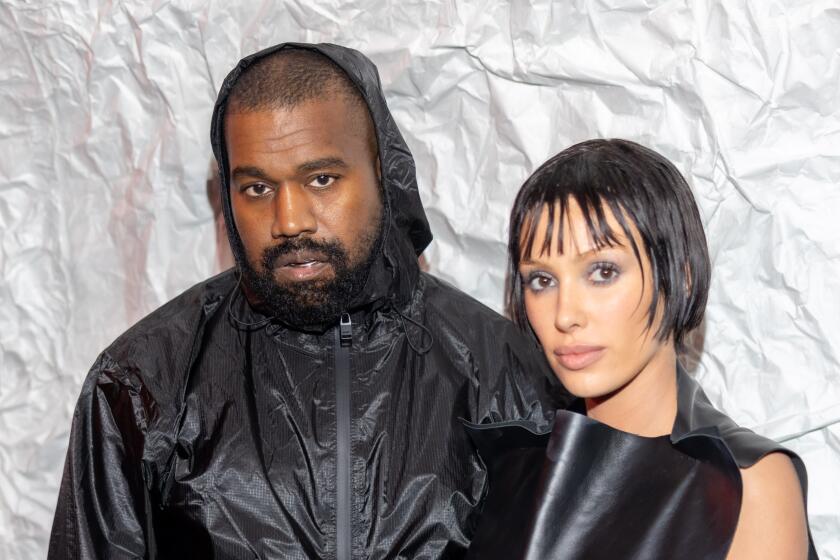

When Monáe signed to Bad Boy, many expressed concern that she’d be transformed into another Danity Kane — a feminine product. But she’s aggressively stuck to her guns in presenting an androgynous image and putting musical talent before sex appeal.

“It’s time to redefine what sexy can be, and what a woman can wear, how she wears her hair, what shoes she chooses,” said Monáe, whose signature pompadour has inspired some to compare her to Grace Jones. “I’m about uniting and helping people become comfortable with who they are. Because there are young girls out there right now going through identity crises.”

Another key aspect of Wondaland is the desire to integrate the avant-garde and pop. One kindred spirit is Kevin Barnes of the band Of Montreal. The androgynous artiste appears on “Make the Bus,” one of the most rocking tracks on “The ArchAndroid.” This indie-pop favorite’s happy union with Wondaland offers another example of how the collective is refusing music’s increasingly outdated categorical divisions. The two groups will tour together in the fall.

“Meeting Janelle and everybody at Wondaland was definitely the most important event for me, artistically speaking, in the last 10 years. It was like discovering the Beatles or something,” said Barnes, reached by phone in L.A., where he’s working on the next Of Montreal album with producer Jon Brion.

“The ArchAndroid” presents Monáe to the pop audience as she stands on the shoulders of her Wondaland community, including guests such as Barnes and the poet Saul Williams, and Wondaland artists such as Deep Cotton and Roman GianArthur. Lightning likens it to George Clinton’s masterpieces with Parliament-Funkadelic, which told a complicated story but also got people to dance.

The album follows the path of Cindi Mayweather, an android whose desire for a shape-shifting human causes her to break free of the bonds of society and reach a higher level of consciousness. Echoes of slave narratives and the struggles of the civil rights movement run through the work, but Philip K. Dick, Andy Warhol and the filmmaker Fritz Lang are equally important muses.

The recording demands active involvement from listeners. Musically, it ranges widely, from Stevie Wonder soul to funk-rock hybrids to shimmery freak folk and James Bond movie-style balladry. Then there’s that story, which requires detailed attention to fully comprehend. Critics and Monáe’s growing cult have embraced the challenge. “The ArchAndroid” is the best reviewed new album of 2010, according to the aggregator Metacritic.com.

With Lightning and Wonder, Monáe figured out how to go beyond her comfort zone of Jill Scott-style neo-soul and to develop a broader vision and more distinctive persona. They recast the usual top-down relationship of producer and “diva” as something far more fluid and equal.

“We’re actually androids when we work. Or cyborgs,” said Monáe, smiling. “We challenge each other as people and as artists. And no egos.”

That’s what the Wondaland Arts Society is all about — creativity emerging in unexpected ways as people free themselves from fixed roles and presumptions. Monáe embodies this spirit; “The ArchAndroid” expresses it. And now it’s up to the world to take it on.

“Whatever celebrity they achieve will be built on being unclassifiable,” said writer-mentor Greg Tate, “which in the long run is where you want to be … free to be freaky as you wanna — like George Clinton and David Bowie in their primes.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.