Book review: ‘Scout, Atticus and Boo’ by Mary McDonagh Murphy

Scout, Atticus and Boo

A Celebration of Fifty Years of ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’

Mary McDonagh Murphy

Harper: 240 pp., $24.99

What is it about “To Kill a Mockingbird”? Harper Lee’s 1960 debut has sold 30 million copies, more than any other 20th century novel, and it continues to sell 1 million more each year. Yet despite having won the Pulitzer Prize and having assumed a place as one of our essential national books of fiction, it remains its author’s only published novel.

To commemorate the novel’s 50th anniversary next month, filmmaker Mary McDonagh Murphy has produced the documentary “Hey, Boo.” The companion volume, “Scout, Atticus and Boo: A Celebration of Fifty Years of ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’” features Murphy’s conversations with both famous and not-so-famous readers about the effect of Lee’s book.

Among the interviewees are Tom Brokaw, Andrew Young, Anna Quindlen and Oprah Winfrey. Murphy also talks to Lee’s minister, the Rev. Thomas Lane Butts; the director of Lee’s hometown museum, Jane Ellen Clark; and Alice Finch Lee, the author’s 99-year-old sister. So it’s a unique club.

And that’s really what reading this book is like: attending a big book club meeting with 26 lovers of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Authors Lee Smith and Adriana Trigiani explain how the character of Scout ignited their feminist awareness. “I think,” the former says, “Scout has done more for Southern womanhood than any other character in literature. She’s turned girls into the kind of women we want.”

Novelist Richard Russo describes how Scout’s father, Atticus, embodied the coveted good father; “[Atticus had] that great ability to trust a child and to understand that a child will know in the fullness of time what it is that you’re trying to get across,” he says.

As for the novel’s impact on the civil-rights movement: “I think Lee helped liberate white people in that book,” Brokaw explains.

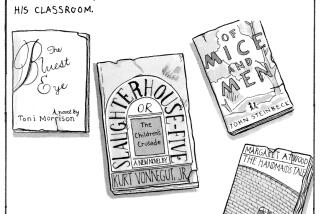

The memories, though, are not all sweet. “To Kill a Mockingbird” is hardly beloved by everyone; it routinely makes the American Library Assn.’s Top 100 list of most requested books to be challenged or banned.

With its segregated Southern landscape, its free-floating use of racial epithets and what is critically seen as derogatory and underdeveloped images of blacks, the novel is severely dated, some say, much like the 1967 film “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.”

“I think Martin Luther King was brave, Malcolm X was brave, James Baldwin, who was gay and black in America and had to move to France, was brave,” says author James McBride in his interview with Murphy. As for Lee, he continues, “I think she did the best she could, given how she was raised. That still doesn’t absolve the book or this country of the whole business of racism.”

The one voice missing here, of course, is Lee’s; she has not spoken publicly about the book since 1964. She lives quietly in her hometown of Monroeville, Ala., having refused even Winfrey, who tells the story in “Scout, Atticus and Boo.”

“I knew 20 minutes into the conversation that I would never be able to convince her to do an interview and it is not my style to push,” she recalls, describing Lee’s polite rejection over lunch. “She said to me, ‘I already said everything I needed to say.… You know the character Boo Radley? Well, if you know Boo, then you understand why I wouldn’t be doing an interview because I am really Boo.’ I knew that was the end of it. I just enjoyed the lunch.”

Kinosian is a freelance critic.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.