L.A. Opera and its $32-million Ring

In Richard Wagner’s “The Ring of the Nibelung,” a pile of sacred gold and a ring that’s fashioned from it are said to confer “measureless might.” However, by the fourth scene of the 17-hour-plus opus, a drawback has emerged: A curse gets attached to the loot, and a colorful assortment of gods, dwarfs, giants and humans spend the rest of the proceedings either succumbing to the hex or trying to set things right.

Achim Freyer can relate. Los Angeles Opera has put him in charge of its own mighty hoard -- the $32 million budgeted for mounting L.A.’s first-ever production of the Ring, a four-part work that connoisseurs consider opera’s Mount Everest. The nearly five-year endeavor is heading into its home stretch.

FOR THE RECORD:

‘Ring’ cycle: An article in the March 21 Arts & Books section about the cost of Los Angeles Opera’s production of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle said chorus members earn the same amount for performances and rehearsals. They are paid less for rehearsals. —

Asked what it’s like to have that $32-million figure attached so prominently to his creation, the 75-year-old director play-acts the public’s response, cupping his face in his hands while registering a look of astonishment and concern. Long esteemed in Europe, Freyer has spent the last several years marshaling a force of more than 350 singers, dancers, designers, technicians, costume-makers and backstage help to tell Wagner’s cosmic tale. “ ‘All that [money], what is it meant for?’ ” he gently cries.

He elaborates in German. “It puts him in a panic to know the audience has that sum in mind, and it puts a lot of pressure on him,” says his translator. Freyer quickly adds that he’s not about to let the pressure get in his way.

The number “has been hung around our neck like a yoke,” says Christopher Koelsch, L.A. Opera’s vice president of artistic planning. “We don’t get a review of the Ring that doesn’t talk about the cost.” When The Times inquired about what goes into a $32-million production, Koelsch welcomed the chance to have the budget “demystified.” He says mistaken assumptions have been flying in operatic circles.

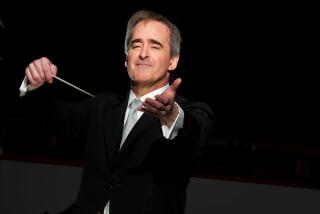

Says Plácido Domingo, who as general director of Los Angeles Opera is overseeing Freyer’s work -- and takes direction from him while singing the role of the doomed hero, Siegmund, in “The Valkyrie” -- “It is my hope that [audiences] will be looking at the art, not at the money that they think has been spent.”

Ringed by expenses

If L.A. Opera had programmed four other new productions instead of the Ring, it could have expected to spend $16 million to $20 million, Koelsch says. Doing the Ring means hiring 82 musicians for the orchestra when about 60 is typical, and 53 stagehands instead of about 40. Huge overtime expenses are a given: Under union contracts, time-and-a-half pay rates kick in for singers and musicians when a show extends beyond 3 1/2 hours -- and each Ring opera except the first, “Das Rheingold,” comes in at nearly five hours.

The lowliest chorus member earns a minimum of $283 plus $94 an hour in overtime for each performance or rehearsal, according to L.A. Opera’s contract with the American Guild of Musical Artists. The company won’t disclose what it pays musicians and leading singers. But stars’ earnings will be in line with what’s been paid in the past, the company says -- and the peak rate typically has ranged from $70,000 to $140,000 per opera. With the Ring, seven singers will be in three of the four operas, and an eighth is in all four.

To illustrate some of the special features contributing to the cost of the undertaking, let’s follow Freyer’s wildly unkempt white mane through the company’s downtown costume shop, where he’s leading us into a forest of hanging Ring outfits that will never be used in front of an audience. They were made just for rehearsals -- because in Freyer’s production, performers don’t merely learn how to play their roles, but must master the challenge of functioning in unorthodox garb that he and his daughter, Amanda, have designed to symbolize the characters’ dramatic meaning. The less lavish practice outfits spare wear and tear on the real ones that the father and daughter have hand-painted into wearable artworks.

Many of the costumes -- sculptures, really -- are manned more than worn, and the 17 singers, 18 nonsinging performers and 70 chorus members who make up the onstage cast must rehearse in them just to adapt. Freyer’s special stage is more than twice as steep as the grade up which some opera-goers will trudge to the hilltop Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, and it rotates. Consequently, all performers receive training sessions -- sometimes with costumes -- just to learn how to move on it safely. It all costs money.

Ambition and reality

The economy was flush when the Ring and its price tag were announced in 2006, along with the stewardship of Freyer, whose soft-voiced bearing makes him seem more like a kindly professor than an exacting eminence who began as a protégé of Bertolt Brecht. Now we’re in a different era, and the production -- rolled out in four stand-alone parts last year and next month, to be followed May 29 to June 26 by three climactic runs through the entire cycle -- is unfolding amid deep indebtedness for L.A. Opera. That includes a $14-million bailout loan from the county Board of Supervisors, collateralized by $30 million in pledges the company says it has secured from board members.

Stephen Rountree, chief operating officer, says the debt didn’t pile up just because of the Ring, but is the result of the ambitious agenda of Domingo’s decade-long tenure. Launched 24 years ago, L.A. Opera made a name as a company willing to try new things.

But new and different isn’t always popular, and there’s no guarantee that the production will generate the $13 million in ticket income and $19 million in donations needed to balance its budget. To break even, Rountree says, nearly 80% of the 3,045 seats in the pavilion need to be filled. With prices ranging from $350 to $2,200 for the full cycle of four operas (except for a few $100 seats with obstructed views), sales are “edging up toward 50%,” he says, but are “a little slow for what we might have hoped.”

In the Ring’s wake will come L.A. Opera’s leanest offerings since the 1990s -- a 2010-11 season of six operas, totaling 42 performances, compared with a peak of 10 operas and 75 performances for 2006-07.

Authorities say that any attempt to mount the Ring, even in good times, is a tremendous stretch for an opera company. Washington National Opera, also led by Domingo, recently had to give up its attempt. San Francisco Opera will scale the mountain next year; the Metropolitan Opera is readying one for 2012, having retired its previous production in 2009 after 20 years’ service.

Given what it requires artistically and technically, “you don’t go 20 minutes without something dangerous coming up, musically or physically or dramatically,” says Seattle Opera general director Speight Jenkins, who has overseen more than 20 stagings of the cycle.

L.A. Opera’s journey to seize the Ring began in 2000 when Domingo, who had just taken over, announced his plan to enlist Industrial Light & Magic, the special effects company George Lucas launched to create “Star Wars.” Rumored production cost estimates ran to $60 million. Then the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks came, the economy tanked and visions of a high-tech Hollywood Ring vanished.

Still, Domingo was determined. Armed with a $6-million donation from philanthropists Eli and Edythe Broad, the quest began anew. Freyer, little known in America until L.A. Opera hired him for unorthodox productions of Bach’s “Mass in B-minor” and Berlioz’s “The Damnation of Faust” in 2002 and 2003, said “no” the first two times he was asked to direct, then relented.

The first version he imagined would have cost about $50 million, says Koelsch, but Freyer scaled it down while keeping the same basic approach we’re seeing now.

The long view

The $32 million may seem exorbitant: After all, the cost of a big Broadway musical typically ranges from about $10 million to $15 million. But on Broadway, budget numbers represent just the cost of getting a show to opening night. In L.A. Opera’s accounting, the big number covers everything -- from Freyer’s first pencil scratch through the fabrication of all the physical elements, the purchase of $750,000 worth of video projection equipment and software and on through casting, rehearsals and 36 performances.

The cost meter will not stop ticking until the L.A. Ring has been dismantled and packed into 11 40-foot-long shipping containers in a local storage yard. The hope is that European opera houses that will scout the production will want to book it, paying fees that could recoup some costs. Someday, says Rountree, Freyer’s “Ring” will be revived here, but not before 2018.

If costs stay within the budget -- Rountree says they are on target -- L.A.’s outlays would appear not to be out of line with what San Francisco Opera plans to spend. There, the top ticket costs $2,800. Created by Francesca Zambello, a prominent American director, it evokes different periods of American history -- starting with a “Das Rheingold” set amid the California Gold Rush. The budget is $24.8 million for 26 performances, says general director David Gockley. That’s $954,000 per performance, which makes Freyer’s Ring, at $889,000, look almost like a bargain.

Among the unusual expenses of L.A.’s Ring were the two week-long “bauprobes” (German for “built rehearsals”) during 2007 and 2008, in which Freyer got an early look at the sets, stage and lighting effects, then tested the flying apparatus and the video projections, which include about 400 computer-generated images. The company normally doesn’t do that, says technical director Jeff Kleeman, but bauprobes are customary for European directors, and for Freyer “it’s part of his process he’s used for 50 years.” Regular rehearsal time for the four stand-alone productions and three complete Ring cycles will total 46 weeks.

Renting the flying gear used in a number of scenes comes to $400,000 over three years, Kleeman says, and expenditures in the six figures went into creating what he and his crew have dubbed “the flipper” -- a sturdy but ultra-lightweight section of the stage designed to lift to reveal the netherworld where a race of dwarfs, the Nibelungs, labor as slaves.

Another unusual cost involves wages for two stagehands who spend six hours or more each performance day tending to custom-made battery packs that power the 3,000 feet of LED tubing Freyer has deployed as props and stage decor.

Kleeman says L.A. Opera saved about $250,000 by forgoing the hydraulic lift that would have given Erda, the earth goddess, a first-class trip to the stage in the scenes in which she emerges through a circular trapdoor. Instead, mezzo soprano Jill Grove will rise on a wooden box hoisted by a forklift. Grove hasn’t objected, says production director Rupert Hemmings.

A good chunk of the money and effort going into the Ring isn’t just an expense, says Kleeman, but a long-term investment that has begun to pay dividends. Because of the Ring, he says, L.A. Opera possesses new skills and equipment it can use for other operas. Next season opens with the world premiere adaptation of the film “Il Postino,” starring Domingo as the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda. Minus the video capabilities acquired to do the Ring, the technical director says, “Il Postino” might not have been possible, requiring $350,000 to rent the projection gear and hire freelance staff to operate it.

Says Rountree: “The Ring is seen everywhere in the opera world as a kind of test of the grown-up, fully capable status of a company, and everybody feels they’ve met this challenge. There’s an immense sense of pride in the house.”

“We’ve all learned more,” says Kleeman, who has worked at L.A. Opera since its inception. “We’re better. Almost anything Achim asks for, you can’t just go out and buy it, or look it up in a textbook. He’s inventive, and if he’s inventive, we have to be inventive.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.