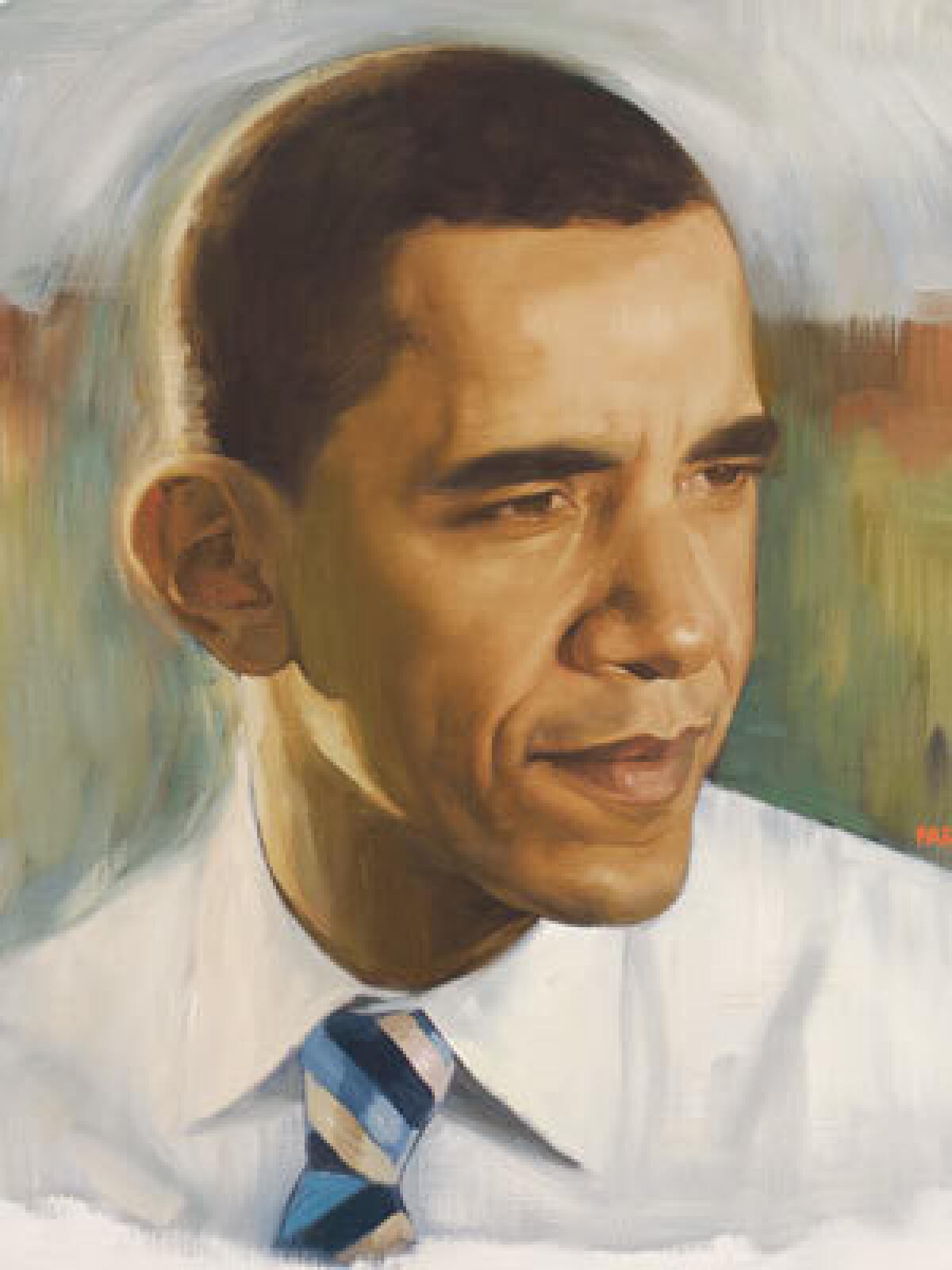

Barack Obama’s election puts the ‘mutt’ front and center

Winding down his first news conference as president-elect, Barack Obama indulged a question about the puppy he’d promised his daughters, Sasha and Malia. He noted there were “two criteria that have to be reconciled.” On the one hand, there was a need for a hypoallergenic breed because Malia is allergic. On the other hand, the family’s politically correct preference for a shelter dog would make it hard to satisfy the first condition because, Obama said, “a lot of shelter dogs are mutts like me.”

There will be at least one mutt in the White House.

It was in that moment that the profound possibilities of rewriting our notions of the American identity hit home for me. For those of us who’ve been preoccupied with the castes of our “casteless” society, this is both an exhilarating and a bewildering time. What has forever been “marginal” is now suddenly in a spotlight at the center of the known world.

There was little hint that we were on the cusp of such a moment. I have been struck by how out of sync Obama’s election is with representations of race in pop culture in recent history. Survey the geography of American literature, journalism and film of the last decade and there is little to be found that presages a “historic election.” Most stereotypes have held their place. Close-ups of interracial kisses still cause titters. The very idea of “mixed race” identity had a few moments (mostly pre- 9/11), but how many Americans today know what “hapa” means, or, for that matter, what a mestizo is?

I think I know why our pop representations did not anticipate the Obama moment (except for, memorably, Jimmy Smits as Matt Santos, who became the first brown president on NBC’s “The West Wing”). It’s because those of us who hold the power of representation lagged behind history, especially in the frenetic movement of the global era. In American popular media, this has been covered more as a phenomenon of technology and commerce, but it was the human migrations, largely from “Third World” to “First,” that set the stage for America’s, and the world’s, great mutt moment.

We didn’t see it coming. Americans often think of the “global” as a phenomenon beyond our borders, or as a foreign-ness that arrives from afar and then -- shock! -- suddenly shows up in our bedrooms. That is because the Americans who have written most of American history feared and loathed how mixed we have long been and have ever increasingly become. And it is not just the “white” that turns away from the in-between, of course. Those of us with “color” can claim identity with stereotypes too.

Obama himself has wandered around in this wilderness where none of us can recognize the other. His extraordinarily thoughtful memoir “Dreams From My Father” finds him resolving the confusion of mixed-ness by moving toward a somewhat fixed notion of blackness, with a helping hand from the Rev. Jeremiah Wright Jr. Whereas “The Audacity of Hope,” written a decade later, reads somewhat like Malcolm X after his visit to Mecca, with Obama waxing much more expansive and exhorting us to leave the baby boomer dichotomies behind. I was much more moved by the first book, which certainly is the better written of the two for the force of its confessional lyric. But the message of “Audacity” (the irony of that title coming from Wright!), in spite of its multicultural clichés, was indeed central to the campaign rhetoric that brought a majority of Americans together to cast their ballots for our first “black” (mixed-race, nonwhite . . . ) president.

Obama’s election in and of itself cannot dismantle a discourse of race that has accumulated power over many centuries. But the image of his body and the narrative of his life playing on a loop for the entire world are tremendously productive. The challenge is to those with the power of representation -- bloggers and poets, filmmakers and songwriters. If the election signified the end of one era, it also proclaims the beginning of a new one, and it is up to us to imagine and represent it.

Martínez is the Fletcher Jones chair of literature and writing at Loyola Marymount University.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.