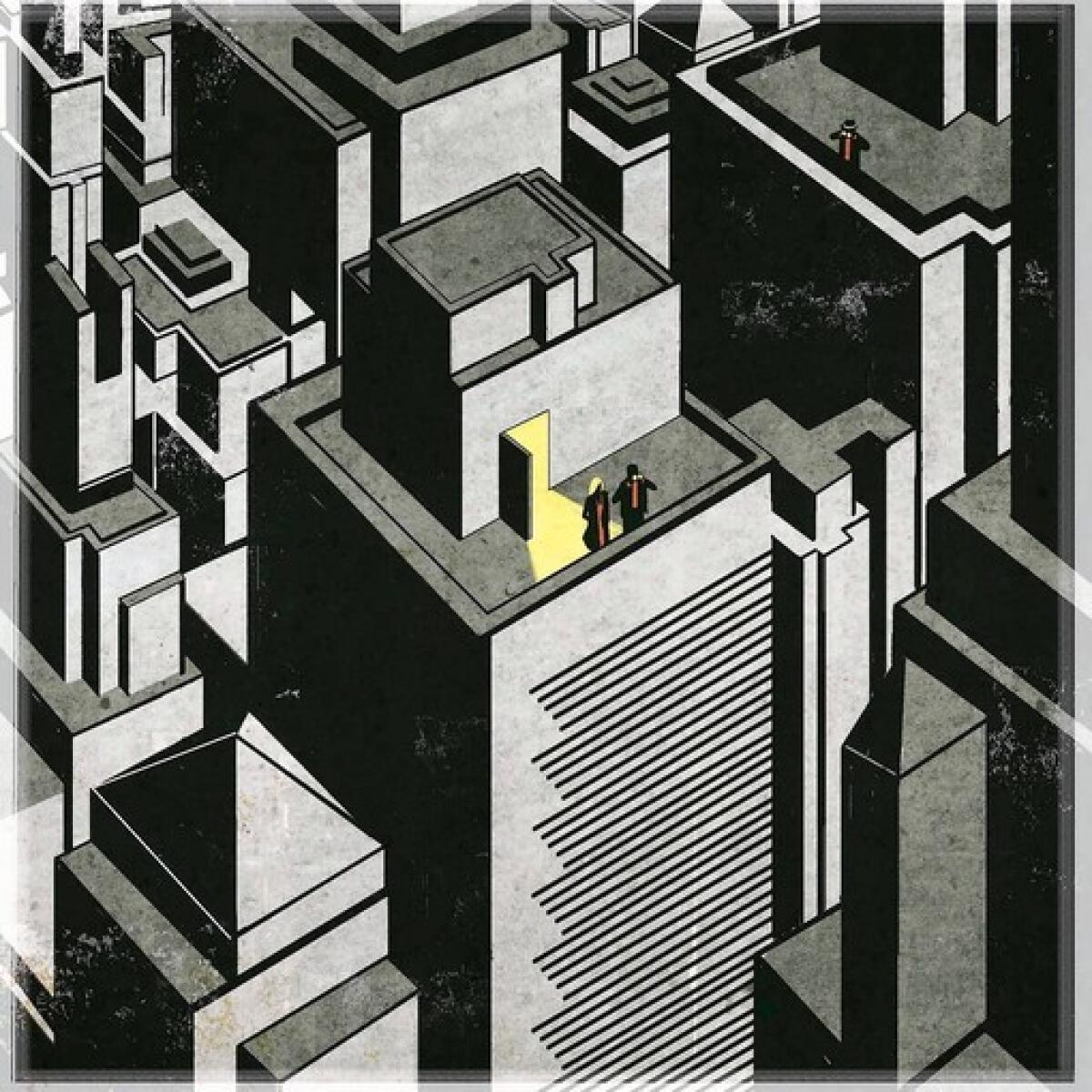

Book review: ‘Zero History’ by William Gibson

Zero History

A Novel

William Gibson

Putnam: 406 pp., $26.95

William Gibson’s post- 9/11 novels offer a fascinating case study in what happens when real life catches up with science fiction. Gibson has always been (to use one of his own phrases) a “coolhunter,” searching for meaning on the cultural fringe.

Back in 1982, he coined the word “cyberspace,” and his “Bridge Trilogy” of the 1990s posited a dystopia in which California split into two states after a devastating earthquake. Then, the World Trade Center came down, leaving Gibson to wrestle with not the future, but with a present that had irrevocably changed.

In early 2003, he published “Pattern Recognition,” perhaps the first novel to deal directly with the destruction of the towers; the fallout from Ground Zero also sifts though 2007’s “Spook Country.” It’s the sci-fi equivalent of what happened to, say, John le Carré after the Cold War ended, although, like Le Carré, Gibson hasn’t so much changed as adapted, finding narratives in the chaos of the current moment along the elusive border between technology and art, control and freedom, image and reality.

Gibson’s new book, “Zero History,” is the third, and final, installment in the cycle, yet unlike its predecessors it is emotionally static, and never quite feels fully formed. Set once again in our post-millennial present, the book revolves around the search for a cutting-edge fashion designer who has gone off the grid, but it is really about the sense of dislocation that has come to be common currency since 9/11. Here, the glittering facades of the culture don’t reveal anything beneath the surface — because nothing is there. The world Gibson traces is one bound by branding, in which we are defined less by who we are than by what we own. Resistance, inasmuch as it is possible, is about “atemporality. About opting out of the industrialization of novelty. It’s about deeper code.”

This idea of a deeper code, a secret history, is vintage Gibson; he has long been fascinated by what he calls “nodes,” a type of social ganglia where unlikely connections may arise. One of the plotlines of “Spook Country,” in fact, featured a magazine called “Node,” which may or may not exist, and a journalist named Hollis Henry, former lead singer for the band the Curfew, who has been contracted to do investigative work.

Hollis is back in “Zero History,” as are the characters Milgrim, a junkie (now recovering) with an eye for detail, and Hubertus Bigend the London-based marketer whose global firm Blue Ant underwrites them all. If this seems a little fragmented, that’s the idea: to reflect a collective collapse where everything is up for grabs. This includes the military and the fashion business, which function as unlikely loci here. “The military, if you think about it, largely invented branding,” Bigend tells Hollis. “The whole idea of being ‘in uniform.’ The global fashion industry is based on that.”

For Gibson, the militarization of the culture is a defining metaphor, offering exactly the kind of cognitive dissonance on which his work has often thrived. Early on, he establishes the novel’s thematic underpinnings — “the underlying design code of the twenty-first-century male street was the code of the previous mid-century’s military wear, most of it American,” he writes, referring not just to fashion but psychology — and throughout the book, he highlights the confluences: In the body armor that Bigend’s messenger Fiona wears while motorcycling through the streets of London and in the “Cartel grade” Toyota Hilux (fitted with armor, bulletproof glass and run-flat tires) in which Hollis and Milgrim are chauffeured around town.

Yet in “Pattern Recognition” or “Spook Country,” there would have been something — some threat, some intuition — to necessitate such precautions; in “Zero History,” these elements feel rote. Partly, I suppose, they’re an expression of paranoia. As Bigend notes, “Even the delusionally paranoid have enemies.” This time, though, the enemies don’t have a lot behind them, leaving a skein of emptiness at the book’s heart. Even when the novel’s darker intrigues manifest, the stakes are never really high enough, nor the dangers particularly real.

Instead, it feels as if Gibson is going through the motions, as if he’s gone back to the pattern once too often, setting up a story — centered by Hollis’ efforts to find that designer — that we’ve seen before. Certainly, this is part of his intention. Both “Pattern Recognition” and “Spook Country” were driven by similarly quixotic searches. Those books, however, came with a sense of urgency, a sense that when the pieces were all gathered, some kind of coherence would emerge. In “Zero History,” that never quite happens: Despite Gibson’s insights into the relationship between trivia and intrigue, it’s hard to believe that so many people with so much power would get so worked up about the creator of a pair of pants.

In the end, this leaves “Zero History” oddly unfulfilling, like a facsimile or a knockoff in which the material that once felt so fresh has come to be a little worn. Gibson may have had to improvise a new kind of science-fiction novel in the wake of 9/11, but the cultural implosion that the tragedy set in motion is now the substance of daily life. “Follow the accident. Fear the set plan,” Gibson writes late in “Zero History.” Once wishes that he had taken his own advice.

david.ulin@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.