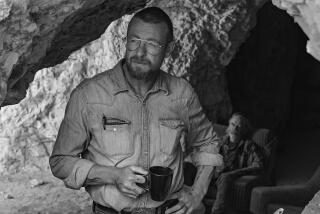

Andrés Dominguez of ‘The X-Files: I Want to Believe’

THERE’S show business, and then there’s snow business. Andrés Dominguez gets to dabble in both. The Chile-born, Canada-raised Dominguez spent 14 years as a sawmill and prop mill engineer before “I just got bored,” he says. In 1991, a friend helped him land a job at a special-effects company, and since then, he’s worked on films including “Seven Years in Tibet,” “Fantastic Four” and “X-Men: The Last Stand.” His first major snow biz job, however, was 1999’s powder-packed “Snow Falling on Cedars.” “That’s big-time snow,” he recalls.

Snow looms large in the paranormal “The X-Files: I Want to Believe,” due in theaters Friday, and Vancouver-based Dominguez, 45, operated as the lead snow man, making sure the Canadian set was sufficiently coated.

Winter wonderland: While shooting on location in downtown Vancouver, Dominguez says his initial instruction was to make the set look “like Alaska: completely covered.” But the city doesn’t get a lot of snowfall, so budget restraints kept the shoot limited to melty snow drifts. “We ended up with a look where it had snow on the sidewalks and the streets are kind of wet,” he says.

Since the set covered some six city blocks, Dominguez had to glue paper snow on foam piles to create snow berms in some areas. But his greatest challenge was working within the city’s time frame. “We would have maybe four or five hours to bring snow in, dress the street and then get rid of it,” he says. “Fortunately, because they wanted it to look like it was melting, it didn’t really matter that it was clean or dirty.”

On thin ice: Some of the city snow came as ice chips from nearby fisheries, which was then dispersed with a mulch blower. Dominguez also collected Zamboni shavings from ice-skating rinks in the area. “You’re doing them a favor because it costs money to get rid of it,” he says. “They appreciate us taking it away as much as we appreciate having it for free.” Plus, “it’s a lot easier than going up and getting the snow from the mountains.”

The snow must go on: After Vancouver, the cast and crew moved production about 100 miles north to a remote outpost near Whistler called Pemberton. Some of his time was spent dressing the set, using rakes and trail-grooming snowcat vehicles. For bigger jobs, he relied on a snow-making machine -- his own mini version of the snow guns used at ski resorts -- to create a flurry. “To make snow, you need lots of air and high-pressure water,” he explains. Ideal temperature conditions are “if the weather’s below zero [Celsius] and low humidity. So when it was minus 10, the machine was running full on. . . . If you do a flat area, you can probably put a layer of snow 4 inches high in five hours.”

Even better than the real thing: “When you walk in the snow so many times, it gets slippery, like ice,” Dominguez says. “So instead of putting more snow down, you’d just put in paper snow. It’s not slippery. All you do is go in there and fluff it up, and [it] keeps the actors from wiping out.” He also used paper snow during a scene where a car slams into a snow-covered bale of hay. “Sometimes the snow is too heavy, and you can’t get it to look like it’s powdery,” he reveals. “We would use a bit of paper snow with real snow, so when the impact happens, you can get that dusting you’re looking for.”

To create falling snow, Dominguez used rice starch. “We use garbage buckets to drop it into the wind machines and send it into the air,” he explains. “It’s super light, so it travels nicely, just like snow. There was a part in the movie where we’re doing the snow, and we’re coming in with the wind machines, and all of a sudden, it starts to snow [for real]. And we’re all like, ‘Wow, it’s exactly the same!’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.