‘Ravens’ by George Dawes Green

George Dawes Green has made an irregular habit of analyzing how extreme circumstances affect the most ordinary of people. His deserved Edgar-winning debut, “The Caveman’s Valentine” (1994), traveled down mystery fiction’s trope-filled streets with a paranoid schizophrenic as tour guide. “The Juror” (1995) was a slick account of how a young woman’s jury turn took a descent into stalker territory, but Green’s knack for wringing maximum disturbance out of a nerve-jangling story line elevated the bestselling novel (and subsequent movie) above similar fare. Even his 14-year hiatus between books, often spent working on storytelling extravaganzas under the Moth rubric, seems appropriate -- especially as the end result is a high-wire act of risk and dreams in constant threat of being snatched away.

“[W]inning the jackpot means you get everything; love, riches, dreams, forgiveness, sky, ocean, shoes, power . . . everything, nothing denied.” Patsy Boatwright believes this, which is why she parks herself in front of the TV every Wednesday night hoping salvation comes in the form of a winning ticket. Daughter Tara believes it because a jackpot win means escape from her mother’s incessant questions about why she dares to be at college when she ought to be working to support her parents and their mounting bills. Jase, Tara’s little brother, believes it because the extra money will buy him the video game console previously denied him. And Mitch, the patriarch of the Boatwright clan, believes it because that way, his business will be saved and his debts will be scrubbed away.

Having set up their circumstances, “Ravens” naturally begins with the unthinkable: the numbers line up and the Boatwrights will walk away with the proceeds of a $318-million jackpot. But, since this is a psychological thriller, an even more unfathomable scenario unfolds when two out-of-work, desperate young men from Ohio on their way to Florida -- the wannabe alpha male Shaw McBride and his longtime best friend, Romeo Zderko -- end up stranded in the Boatwrights’ hometown of Brunswick, Ga. Like a series of dominoes clacking on a collision course of chance, a stray remark leads the duo to the Boatwrights’ doorstep, weapons at their disposal, ready to embark on an escalating reign of terror whose price is half the lottery winnings.

Green, however, has larger aims than just delivering a hostage crisis narrative with a necessarily violent and cathartic climax. Much of the disquieting pleasure of “Ravens” comes from how he subverts the typical lower-middle-class Southern family, jettisoning sweetness and light for wilder, nastier streaks. Tara’s disdain for her mother imbues her ability to play the part of coquette to Shaw’s threatening pose, but the line between act and reality blurs often for her. Patsy, placed in danger, would sooner fall under the spell of Stockholm syndrome than save her family’s skin. And the lone cop in the story who might be in a position to free the Boatwrights from their horror is viewed as a buffoon, barely able to assert his manhood.

Shaw and Romeo aren’t typical villains, either, as their frantic desperation plays out in different ways. Shaw relishes his newfound role of master manipulator, playing the Boatwrights off each other and off a town all too willing to accept him as a handsome stranger taken in by the family. Romeo can’t quite accept his role of brazen assassin, ready to strike at Shaw’s decree, even as that prospect is all too plausible: Romeo’s “problem, as he saw it, was a lack of hate. Not enough hate. The brain of a revenge killer, he thought, should be spiky with hate. . . . He should make himself dizzy with hate, should work himself into the same whirling froth he’d been in that time in Hollow Park, when he was ten years old and he’d beaten the hell out of Shaw’s mutineer.” All told, the character shades are more charcoal than gray, but Green succeeds because he consistently puts human motivation at the forefront.

The most surprising part of “Ravens” is how deeply it explores religion, a subject practically taboo in contemporary crime fiction. Patsy, on learning of her lottery win, openly cries, “GRACE OF GOD! GRACE OF GOD! GRACE OF GOD!” Tara, when first faced with Shaw’s murderous intentions, tries to pray, “but every prayer flew from her head.” Later on, when the tension grows unbearable, Tara “knelt and clutched the bedclothes and sobbed, and when she thought of the Lord the face she saw was Romeo’s -- she couldn’t help it! She couldn’t help it!” Mitch prides himself on deep religiosity, but his faith is sorely tested by Shaw’s messianic complex, confirmed and cajoled by the community in a disturbing, darkly satiric scene mirroring the Holy Communion at Sunday services. Even Jase comes to feel guilt at his perceived fault that he’d “been sent here to destroy everyone’s life. Like [he was] secretly working for the devil.”

The stark good and evil imagery of Christianity stands in contrast to the ever-shifting quicksand of moral dilemmas, and what comes through in “Ravens,” despite the coincidences needed to spur along the narrative, is how the naked need for money, power and love strips away the prospect of a cathartic journey to redemption, turning hope inside out -- and back upon itself.

Weinman writes Dark Passages, a monthly mystery and suspense column, for latimes.com/books and blogs about the genre at www.sarahweinman.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

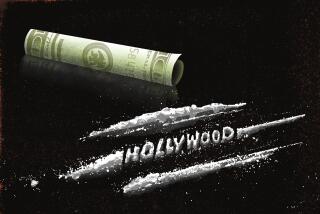

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.