Putting art to music, with wondrous results

Did you hear the one about the composer who walks into an art gallery?

If you are expecting a punch line — sorry. It’s not a joke. When a composer walks into an art gallery or catches sight of an artwork somewhere else, there might be something worth hearing down the line. It happens all the time.

Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” and Debussy’s wondrous “La Mer” (inspired in part by Hokusai’s “Under the Wave Off Kanagawa”) are perhaps the most popular examples of composers aroused by art. But the list goes on. Wassily Kandinsky influenced Arnold Schoenberg, as Paul Klee did Pierre Boulez.

Part of the New York Philharmonic Biennial last month was a concert at the Museum of Modern Art of recent works that took their impetus from sculpture. Also last month, the Ojai Music Festival offered a late-night performance of Morton Feldman’s “Rothko Chapel,” music that captured the aura of the room for which Mark Rothko made his final mystical paintings.

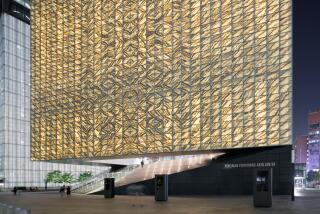

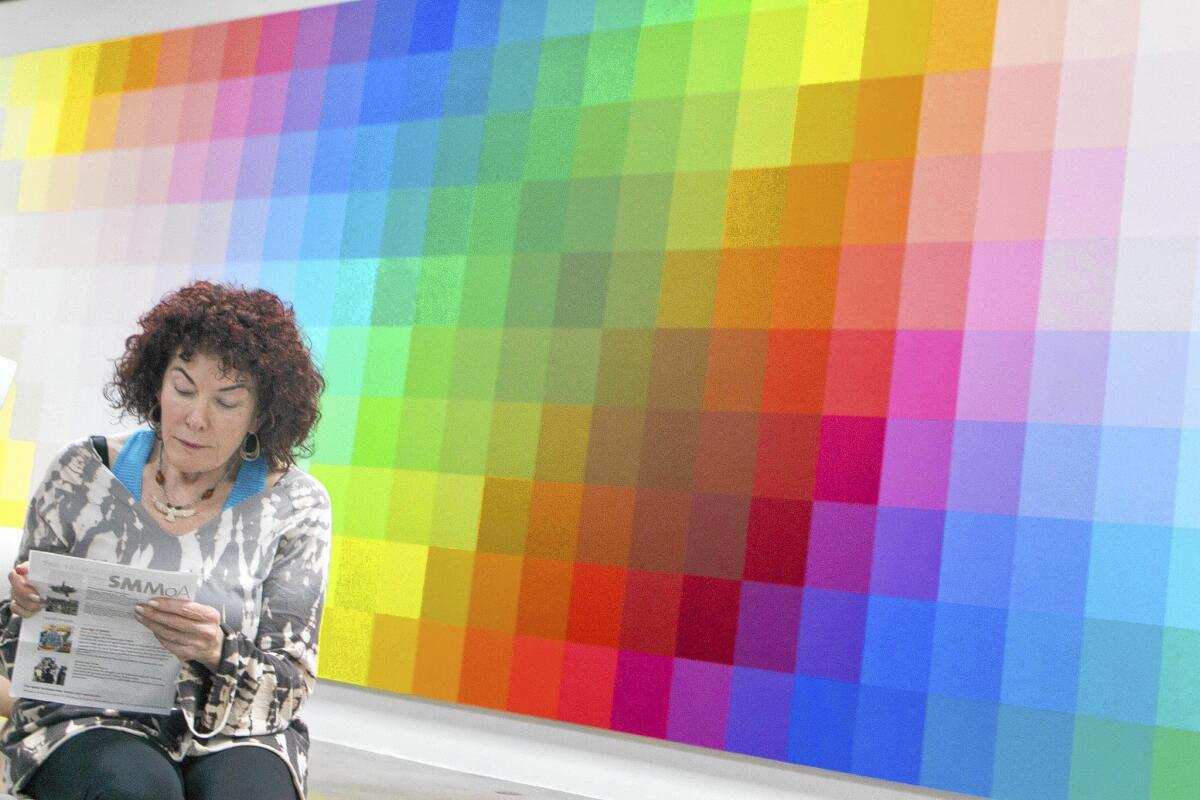

Over the weekend, we had the results of two composers having walked into exhibitions in Pasadena and Santa Monica. On Friday night, Vicki Ray premiered Joseph Pereira’s “Five Baroque Settings From the Norton Simon” as part of her Pianos Spheres program at the Boston Court Performing Arts Center. On Saturday afternoon, Mark Trayle fabricated an electric soundscape to accompany Robert Swain’s “The Form of Color,” a Santa Monica Museum of Art exhibition of large, pulsating paintings made up of small grids of color that seem to set the room vibrating.

Pereira, principal timpanist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, said in brief remarks to the audience that on his first visit to the Norton Simon, he surprised himself by not making his usual beeline to the museum’s contemporary wing. Instead, 16th and 17th century Spanish and Italian paintings caught his eye. Ironically, the Norton Simon was, in its previous existence as the Pasadena Art Museum, primarily devoted to modern art, with a history of hosting contemporary composers.

But Pereira is nonetheless a modernist, and rather than trying to depict a painterly narrative in music, he was more attracted to the meaning of techniques — how, for instance, Francisco de Zurbarán’s use of light alters perspective in the Spanish painter’s only still life, “Still Life With Lemons, Oranges and a Rose.”

There were no reproductions (or even descriptions of the paintings) provided. These weren’t paintings accompanied by music but rather paintings as stimulants for music. Dazzling tinkling filigree characterized Pereira’s take on Jusepe de Ribera’s “The Sense of Touch”; heavy chords gave weight to Giovanni Battista Moroni’s “Portrait of an Elderly Man”; room-chilling tremolo set the sonic mood for Giovanni Francesco Barbieri’s “Suicide of Cleopatra”; shimmering chords were an unstill result of Ribera’s minimalist still life. And finally, there was the virtuosic roller-coaster ride through Guido Cagnacci’s “Martha Rebuking Mary for her Vanity,” chosen perhaps as a nod to Pereira’s participation in the L.A. Phil’s premiere of John Adams’ “The Gospel According to the Other Mary.”

Ray’s thrilling recital also included works by George Crumb, three piquant European works that required Ray to intone texts while playing and Donnacha Dennehy’s glitteringly hot 14-minute effusion over a single harmony (“Stainless Staining”). Of special beauty was Christopher Cerrone’s “Hoyt-Schermerhorn,” a brilliantly solemn intoning of pianistic bells by the composer of the opera “Invisible Cities,” evoking a preternaturally transformed Brooklyn subway stop.

Trayle’s performance at SMMoA was, in one sense, a very different sort of event. The composer sat in the center of the gallery at a table with his electronics. The audience sat in one of four directions, facing Swain’s large canvases. The sound was in four channels, a loudspeaker in each of the room’s four corners. We meditated for 50 minutes on the art, with the sound our guide.

Swain’s paintings consist of gradations of color made by the many blocks of single tints. From a distance, you sense color as motion. But looking close up, I found myself mostly focusing on single panes of color, predictably drawn to bright colors when the electronics were high and loud, to dark blues during gurgling watery passages and to earth tones when the textures got thick.

In fact, textures seemed to be what Trayle’s performance was all about. Just as Pereira became fascinating finding a musical play of light as a complement to Zurbarán’s puckered lemon, Trayle’s granular electronic surfaces drew the eye to Swain’s granular surfaces. Indeed, his yellows were as crinkly as a lemon’s skin.

Before Trayle began, I saw Swain’s paintings as great swaths of earth and sky as seen from afar. During Trayle’s performance, I saw Swain’s forms of color not as forms but as part of the world in which we live immersed. When it was over, I was again looking distractedly, as if outside of time.

Twitter: @markswed

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.