Some like it not: Grotesque ‘Forever Marilyn’ leaving Palm Springs

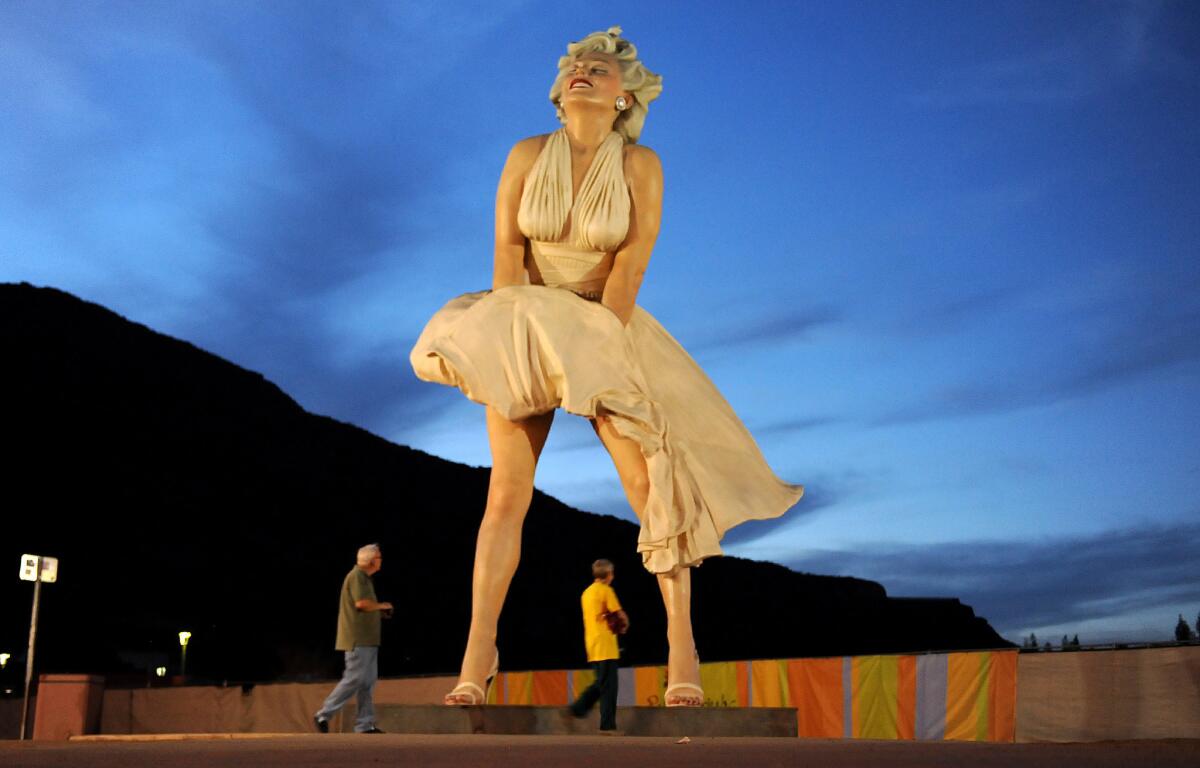

Good news out of Palm Springs this week: Work has begun on dismantling “Forever Marilyn,” the grotesque colossus fabricated with typical ham-handedness by sculptor J. Seward Johnson, which has been marring an already vacant lot at a prominent downtown corner for the last two years.

The sculpture is headed out of town by flatbed truck for an exhibition back East. Good news because good riddance.

“Forever Marilyn” is a 26-foot-tall leviathan whose claim to notoriety is that it besmirches the memory of a marvelous 1955 movie by the late, great Billy Wilder. In “The Seven Year Itch,” a witty film adaptation of George Axelrod’s frothy play, a Walter Mitty-type husband (Tom Ewell) is sorely tempted to be unfaithful by a beautiful if unwitting upstairs neighbor (Marilyn Monroe). Johnson’s leaden sculpture is a cheesy pastiche that fumbles an indelible moment in the film.

In the sweltering heat of a New York City summer, the nameless blond who inspires the philandering itch keeps cool by storing her underwear in the refrigerator. The chill, needless to say, doesn’t last all that long.

PHOTOS: Marilyn Monroe at 50th anniversary of star’s death

Coming out of a movie theater where, appropriately enough, she has just watched the tortured monster movie “Creature From the Black Lagoon,” Monroe stands eagerly atop a sidewalk subway grate. The breeze of a speeding train beneath her feet blows up her billowing white halter dress. The depleted coolness hidden within is momentarily replenished.

Many things make the scene iconic, but one is paramount: Visually, Monroe’s ballooning dress enacts the emotionally teasing temptation that Ewell’s character so deeply feels.

So we feel it too, sitting out there in the movie theater’s dark solitude. Wilder draws a bright erotic line beneath the steaming hot target of the tempted husband’s lust; but, like him, enthralled viewers never glimpse the bull’s-eye.

So what does Johnson, ostensibly a visual artist, do in his sculpture? He lets us under Marilyn’s skirt.

Virtually copying a still-photograph of Monroe in the movie, he blows up the figure to gargantuan size, apparently to mimic the epic magnitude of the movie star’s enduring fame. Now able to walk underneath, we discover what she’s wearing: big girl panties, at that scale somewhere between bloomers and a parachute. Monroe gets dehumanized (once more) as just another trophy celebrity.

Artistically, “Forever Marilyn” is less interesting than the old, anonymously fabricated Rocky and Bullwinkle statue that once graced Jay Ward Productions on the Sunset Strip — an unpretentious 1960s publicity stunt for the satirical TV cartoon. Her gigantic wide-stance transforms her into a figurative Arc de Triomphe, while camera-wielding tourists are pandered to as the victorious army marching through.

PHOTOS: 6 iconic moments with Marilyn Monroe

Of course that is probably why PS Resorts, a local desert tourism organization, brought the ugly sculpture to town in the first place. No doubt it’s also why the group hopes to bring it back in the future — perhaps permanently, if the city can muster the funds to buy it and Johnson decides to sell. Ugh.

Johnson is no Andy Warhol. In the aftermath of Monroe’s 1962 suicide, Warhol seized on her image in a publicity still for “Niagara,” the 1953 film noir that made Monroe a star. In one incisive stroke, Warhol’s repetition of her blurred face undermined the declared aspiration of New York School painters to represent “the tragic and the timeless” exclusively through abstract art. Until then in postwar America, who was more timeless, more tragic than she?

Johnson’s 34,000 pounds of wasted stainless steel will soon be carted off to New Jersey — but not, unfortunately, to a landfill. There it might at least join the celebrated ranks of the “Monuments of Passaic,” the chronicle of inevitable natural, social and cultural decay charted 40 years ago through the state’s deteriorating industrial infrastructure by Land Art innovator Robert Smithson.

Instead it will be going to Grounds for Sculpture, a nominal public petting zoo for art conceived 30 years ago by a wealthy aspiring artist — an heir to the Band-Aid and Tylenol fortune named J. Seward Johnson. (Johnson & Johnson is headquartered in the state.) His colossal kitsch will join 150 other examples of his work in what is being billed as a retrospective; actually, given the venue, it will just be a vanity display.

Grounds for Sculpture is located in suburban Trenton, 10 short minutes down the road from the New Jersey State House. Perhaps Gov. Chris Christie or an aide can initiate a helpful traffic jam to discourage unsuspecting visitors.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.