‘Grief’ in repressive beige

Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf describes “Grief,” his recent series at M+B, as an exercise in “the choreography of emotion.” You could also call it a study in beige, which would seem almost oxymoronic -- is there any color less emotive than beige? Given the delicacy with which Olaf achieves it, however, this muted quality is key to the work’s surprising poignancy.

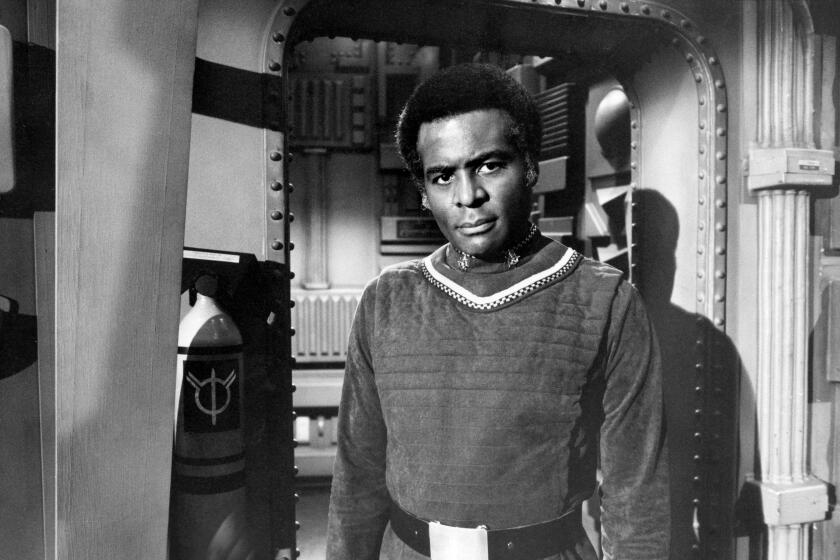

Each photograph depicts a single figure in an elegant Modernist interior, suspended in melancholic reverie. The characters, meant to evoke Kennedy-era aristocracy, include a young man named Troy and several exquisitely poised women with tailored dresses, sculptural hairdos and names such as Irene, Victoria, Sarah, Caroline and Grace.

There’s no explicit narrative, but the tone is bleak. The figures sit alone at tables set for two; they lean blankly against doorjambs and stand at windows clutching handkerchiefs, gazing through translucent curtains.

The mise-en-scene is flawless: nothing out of place, not a blemish or scratch, not a single anomalous or superfluous object. The lines are clean and meticulously composed, with an emphasis on the vertical, particularly in the curtains, so as to suggest the atmosphere of a prison.

But for the modest peach of Sarah’s floral-print dress and the pumpkin hue of Caroline’s blouse, the tones rarely stray from the cream-to-mahogany spectrum. The air is oppressively still.

For all this artifice, one would expect the work to feel cold or contrived, but it doesn’t. The effect is similar to that of a Douglas Sirk film: stylized but not hollow, the artifice crystallizing the emotion rather than replacing it. The characters are abstractions, but the sentiments they embody -- loss, entrapment, repression -- are palpable and distinct.

Olaf’s past work, while similarly meticulous, hasn’t been nearly so reserved. Leering clowns with dripping makeup, naked models with designer shopping bags over their heads, elderly women in pinup poses, ice queens with rasps plunged into their hearts, and a good many rope-bound breasts and penises -- this is Sirk via Robert Mapplethorpe and David LaChapelle, which may explain why the beige feels not quite so dull: Olaf grasps the nature of the more dangerous colors -- the more violent emotions -- but this beige is cultivated to smother the human chaos these neat lines attempt to contain.

In one of the show’s most compelling images, Troy kneels in a living room, the back of his hand raised to his nose as if wiping away tears. The image stands out because it is the only near slip: the only flicker not of emotion -- there are a few other tears -- but of physical awkwardness. The women, one gathers, would never so betray themselves. In this world, they are the keepers of order. It is a role Olaf seems to both admire and pity.

M+B, 612 N. Almont Drive, Los Angeles, (310) 550-0050, through Oct. 20. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.mbfala.com.

Sinking deep into a gray haze

The paintings in “Art Therapy,” Brad Spence’s third solo show at the Shoshana Wayne Gallery, are about the size of picture windows and read like snapshots of a very hazy journey -- say, to the office of a psychiatrist. Rendered in soft, airbrushed acrylic with a predominantly gray palette, the works suggest a state of being muffled by depression, delusion, grief or some cocktail of the drugs often employed to alleviate those feelings.

Some depict details of a landscape viewed through a melancholic (or obsessive) reverie: fog settling on a rocky shore, rain on a sidewalk, a knot of electrical wires. Others suggest memories: an empty room or a deserted beach.

Some speak to the experience of therapy itself. One unsettling piece, “Literature,” depicts an empty waiting room (the title refers to the pamphlets on the table). Others involve homely products of therapeutic expression: a clay sculpture of a woman holding her head in her hands or a family of figures made from cloth, yarn and toilet paper tubes.

What brings the show together, sharpening the psychological effect while deepening the emotional resonance, is the virtuosic -- indeed, magical -- quality of the painting itself. The forms seem to hover just off the surface of the canvas, as if composed entirely of mist; the tones are subtle and delicate.

The most spectacular is a 5-by-7-foot piece depicting the play of light through what looks like a shattered pane of glass. The spatial context is ambiguous but the visual effect stunning.

At close range, the canvas seems to contain nothing but clusters of pale dots. Step back a few feet, however, and the image leaps to life, brilliantly illuminated. It is the show’s one moment of revelation -- the epiphany that penetrates the haze of this rather dreary journey, implying the potential for transcendence, whether toward earthly illumination or the white light promise of an afterlife.

Shoshana Wayne Gallery, 2525 Michigan Ave., Building B1, Santa Monica, (310) 453-7535, through Oct. 27. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.shoshanawayne.com.

Ocampo’s ‘Kitsch’ is good ugly art

“Iconoclast” is one of those flashy terms that’s often thrown around with little deference to its meaning, but Manuel Ocampo is an artist to whom it genuinely does seem to apply. Immersed at an early age in the vocabulary of Spanish Colonial religious painting -- he grew up in the Philippines -- he’s spent most of his career routing symbols and icons out of the culture at large, setting them adrift in his paintings and turning their weight back upon themselves in impressively unpleasant ways.

In the early work, his targets were relatively explicit: colonialism, Roman Catholicism and capitalism. By his last show at the Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, in 2005, this ire had shifted largely to the art world. (One painting in that show was emblazoned with Ad Reinhardt’s classic cartoon words “Ha ha what does this represent?”) In his current show, the critique is somewhat more diffuse, morphing into a sort of personal symbology that seems to defy myriad institutions at once: a snake in a vest and bow tie hanging on a cross; a cross with a ham hock dangling from one arm; a table in the shape of a Star of David cluttered with coins; a ring of sausage links; a broken bottle; a skull and a roll of toilet paper, with a swastika hovering nearby.

Underscoring it all is a clear distrust for traditions, systems and movements of all kinds, evident in the show’s tongue-in-cheek titles, among them “Kitsch Recovery Progrom” (the misspelling is deliberate) and “Monument to the Failed Liberation of the World.”

The brilliance of the work lies in its unrepentant ugliness. I’m not sure it’s possible to genuinely “like” these paintings: They’re busy, scraggly, dingy and awkward, giving you nothing very appealing to hold on to. You’re left instead having to look and think, which is clearly what Ocampo -- an undeniably accomplished technician who underplays his skills on purpose -- would prefer.

Lizabeth Oliveria Gallery, 2712 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles, (310) 837-1073, through Oct. 27. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.lizabetholiveria.com.

They complement but don’t complete

“State Line,” a two-person show at the Jail Gallery, explores the intersection of art, place and politics with visually appealing if conceptually inconclusive results. The artists, Bill Kleiman and Chris Pate, have distinct sensibilities but mesh nicely, each complementing the other’s sense of formal exploration.

The show’s impressive centerpiece is Kleiman’s “A La Carte,” a 9-by-33-foot wall piece made of red, white and blue plastic squeeze toys (they actually look like fragments of wooden molding) fashioned into a flat, vaguely Islamic pattern with the work’s title written atop it in green Arabic letters. Look closely and you’ll find that the red and white elements of the pattern shelter little blue Stars of David.

In a pair of other works, titled “Requiem,” Kleiman repeats similar patterns on a smaller scale, in plastic boxes resembling those hand-held games in which the player maneuvers a tiny ball through a labyrinth.

Pate’s contribution consists of about half a dozen midsized collage works. The strongest, installed across from Kleiman’s piece, involves a silk-screen print of several skulls coalescing inside a frame of blue and red stars -- a curious echo of Kleiman’s ironically patriotic palette.

Pate’s other works are geographical portraits, in a sense: collages devoted to states made up of materials pertaining to those states (maps, printed fabric and so on). They’re abstract compositions, primarily, and certainly attractive.

They do lack the political edge of the other works and skirt the edge of gimmickry. On the whole, however, the show is a compelling meditation on the artist’s place in the world now that is heartening to encounter.

Jail Gallery, 965 N. Vignes St., No. 5A, Los Angeles, (213) 621-9567, through Oct. 27. Closed Sundays through Tuesdays. www.thejailgallery.com.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.