iPad’s book-like touches may appeal to traditional readers

When Apple’s iPad debuted on April 3, it was greeted in some quarters of the tech world by a chorus of critiques. With no phone, no camera and no multitasking, how could it be revolutionary? And yet, when it comes to the iPad’s e-reader, revolutionary is exactly what it might be.

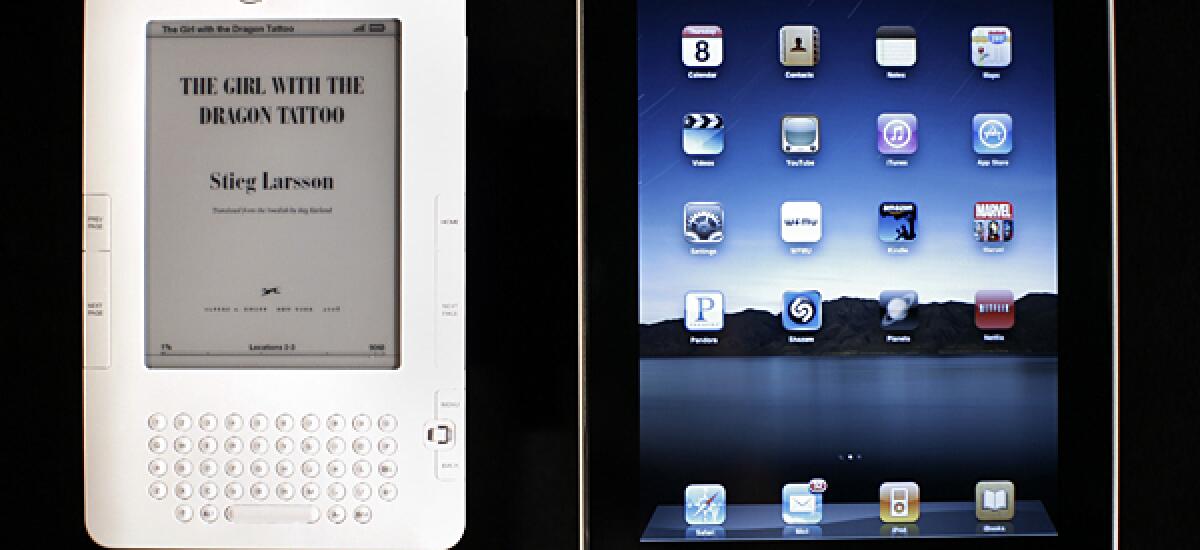

It’s not just that the iPad is beautiful. Nor is it just that the touch-screen interface is more intuitive than the controls on the plastic shell of the Kindle -- which up to now has been the dominant e-reader.

So what is it? Simply this: Books on the iPad are electronic without losing their essential bookness, in a way that e-books haven’t been before.

Of course, the Kindle -- which Amazon.com launched to great success in 2007 -- has avid fans who love its nonreflective screen, which makes it easy to read in sunlight; its huge selection of e-books for sale and download; and its very light weight.

But the Kindle already looks and feels outdated: Its black and gray screen brings to mind a black-and-white TV. Its controls can generously be described as clumsy.

The full-color iPad screen is almost twice as big as the Kindle’s. This makes a tremendous difference: If the Kindle screen is roughly the size of a single paperback page, the iPad, turned sideways, presents two pages side by side. Both enable readers to customize font size, but there will always be more words on the iPad page, more content to digest. The reading experience more closely resembles that of reading a physical book.

Of course, e-books are not physical books. On a Kindle, they aren’t even calibrated in terms of pages; rather, each screen of text is called a “location,” and a 300-page novel will have thousands of them, which makes it hard to keep track of where you left off.

The iPad, on the other hand, sticks with the more traditional designation and also indicates how many pages remain in whatever chapter is on the screen.

What this acknowledges is that there is a rhythm to reading: The first page of a heavy Harry Potter book promises 600 more; the thinning final pages of an Agatha Christie novel clue us in to the mystery getting sorted out. The iPad builds that into the e-reading experience.

The Kindle and the iPad have a progress bar to show how much of a book is left to read, but the Kindle frames its tally in terms of percentages. That’s a telling choice, suggesting that the Kindle is a device that frames its books as data, while the iPad is designed for engaging with the material. Indeed, since every control on the iPad, save for the home key, is on the screen, you’re constantly in contact with your electronic book.

There are other book-like touches: turning a page on the iPad, as with several e-reader apps for the iPhone, features a touch-controlled animation of the page flipping, as quickly or slowly as your finger moves across the screen.

In addition, these pages look like pages -- with (virtual) edges and a crease in the middle of any two-page spread. When you open the e-reader app, you see the image of a wood-grain bookshelf, on which your e-book library is kept. (In a charming touch, the bookshelf swings open like a secret door to access the ibookstore.)

Although the Kindle is, as an Amazon.com spokesperson told me, “purpose-built” for reading, it seems to have lost an essential connection to books. You can do many things with its e-books -- search them, make notes, leave bookmarks -- but you have to learn its interface. The Kindle feels like an e-reading device, whereas an iPad feels like reading.

It’s possible that all the iPad’s book-like touches will eventually be shadows of a left-behind technology. But to me, it signals something more elusive: that books have a specific and unique shape.

Now that we consume so much content electronically -- websites and news and blogs, e-mails and text messages -- it’s unclear how the book will adapt. Will it have embedded video? Will it include links, like a Web page? The best aspects of the iPad’s e-reader show that even as books morph, there are certain things that make them distinct.

To demonstrate this potential, Apple has loaded its ibooks app with a free copy of “Winnie the Pooh” by A.A. Milne, with illustrations in full color. For the last week, I’ve handed the iPad to everyone I know -- generally a bookish lot, I admit -- and almost everyone was wowed by “Winnie the Pooh.” The layout is airy, full of space and light. Change the font, and the page readjusts, the text rewrapping around the images, the flow of the book intact.

“Oh, now I want one,” they tell me. “Now that I see what it can do.”

To be sure, this is Apple’s first tablet, and it will doubtlessly be upgraded. For one friend, that’s a compelling reason not to buy it: “This is 1.0!,” he argues, as if a first-generation product is as dangerous as poisoned Kool-Aid.

In some sense, he’s absolutely right. With no camera or phone, the iPad is a step back from the iPhone. It’s more closely related to netbooks but lacks their capacity to multitask, and there are other tablets on the way. Even its ibooks app isn’t perfect: Users can’t yet leave notes in their books, and the bookstore could use more stock.

Still, the iPad comes after the Sony eReader, the Kindle, Barnes & Noble’s Nook; in that way, it’s a next-generation interface.

Technologically, it’s far ahead -- an app-ready netbook, able to surf the Web, send e-mail, play movies, music and games.

But most important, it has created an interface for e-books that considers what makes books special: They are tactile, they can be beautiful, and they have a beginning, middle and end.

carolyn.kellogg @latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.