From the Archives: James Horner may add Grammys to his ‘Titanic’ Oscars

James Horner recently confessed on the day that he was supposed to start recording his “Titanic” score for James Cameron that he was actually recording a song for “Mighty Joe Young.”

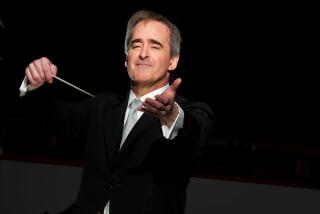

Oscar-winning composer James Horner, perished Monday after his single-engine S312 Tucano turboprop plane crashed in the Los Padres National Forest near the border of Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. He spoke to The Times in 1999 after he was nominated for three Grammys for his work on the “Titanic” soundtrack. He went on to win in all three categories:

For composer James Horner, the “Titanic” merry-go-round has started spinning again, two years after he started writing music about the doomed ocean liner.

Horner last week received three Grammy nominations, for record of the year, song of the year and best song written for a motion picture or television, for his work as co-writer and co-producer of “My Heart Will Go On,” the movie’s enormously popular Celine Dion song.

Horner has already received two Academy Awards for the music--best original score and best song, the latter shared with lyricist Will Jennings (also a double-Grammy nominee for the tune)--not to mention a reported $20-million-plus payday for the soundtrack album, which has sold an estimated 26 million units worldwide.

Reached in Dublin, where he is at work on a dance project, Horner said, “Obviously I’m very flattered. It rekindles everything in a way. It’s like getting spun up in the whirlpool again.”

The surprise about the Grammy nominations was the lack of any recognition for Horner’s “Titanic” score itself, which was a disappointment to the composer.

“It’s hard to know how these things work,” he said. “You never know whether too much success breeds contempt, or whether people in the music industry didn’t like it. You have all kinds of self-doubts as to why it might have happened or might not have happened.”

Horner may have thought the “Titanic” phenomenon was finally behind him. He has written three scores since, for two of the year’s biggest box-office hits, “Deep Impact” and “The Mask of Zorro,” and most recently for the Disney remake of “Mighty Joe Young,” which has opened to disappointing box office.

The 45-year-old composer can’t escape the fallout from “Titanic,” however. Not only has it made him one of the richest musicians in Hollywood, but recent TV ads for “Mighty Joe Young” boast attention that is virtually unheard of for a composer: a separate card trumpeting “music by Academy Award-winning composer James Horner.”

In fact, Horner recently confessed, on the day that he was supposed to start recording his “Titanic” score for James Cameron, he was actually recording a song for “Mighty Joe Young.” The ape movie wouldn’t be released for another year and a half, but director Ron Underwood was about to start shooting his African sequences (in Hawaii) and the script called for a lullaby to be sung on-screen.

At day’s end, Horner recalled, “Jim called to say, ‘How did it go today?’ ‘Oh, great, made a lot of headway,’ ” the composer fibbed. Work on “Titanic” would begin a day late.

Horner’s wistful melody--which reappears in choral and orchestral form throughout “Mighty Joe Young”--also sports a lyric by his “Titanic” collaborator Jennings. The tune, called “Windsong,” was translated into Swahili for performance in the film.

What “Joe” doesn’t have is a jarring contemporary version of the song over the end titles. Explained director Underwood: “James and I both felt that doing a pop version of ‘Windsong’ would really undermine the African feeling and the truthfulness of the score for the film. It didn’t feel appropriate.”

Underwood wanted Horner because of his facility with music of other lands, which is on display in both “Titanic” (the Irish sounds) and “The Mask of Zorro” (Spanish influences).

“James has a way of taking another culture’s music and integrating it into a score without losing the emotional, thematic elements that are needed for a movie,” he said.

But strict authenticity isn’t always required, Horner contends. So although he used some African drums, there are also Japanese taiko drums and Peruvian flutes in the “Joe” score.

“Sometimes one instrumental color is so important to a movie. Only four notes from an Uilleann pipe can say something that no other instrument could say in a hundred notes.

“I used a lot of Japanese drums in ‘Braveheart,’ ” Horner explained. “Those big battlefield scenes were all done with big Japanese ceremonial drums, low Tibetan droning tubes and Swiss Alp horns to create this sound. So it ends up being not literally Scotland or not literally Africa. It’s an impression of it. It’s like painting.”

Until “Titanic,” “Braveheart” was probably the best known of Horner’s 80-plus film scores. The Scottish-flavored music spawned two soundtrack albums and was Oscar-nominated, as was his music for “Apollo 13” the same year. He received previous Oscar nominations for the scores of “Field of Dreams” and “Aliens” and the song “Somewhere Out There” from the animated “An American Tail.”

He also has--so far--three Grammys (two for “Somewhere Out There” and one for the score for “Glory”) and two Golden Globes (for the song and score of “Titanic”).

But, he insists, all the awards and money haven’t altered his lifestyle or his attitude toward his work. “Nothing’s changed for me. The depths and the heights of the movie business are so extreme that I just try very hard never to feel too exalted or too depressed at any time. I try and keep a straight course. I hang out with my family a lot, which tends to ground me.” Home is a secluded house in Calabasas that he shares with his artist wife, Sara, and two daughters.

The son of famed production designer Harry Horner (“The Heiress,” “The Hustler”), Horner spent his formative years in England. He returned to the states in the early ‘70s, completing his musical education at USC and UCLA, where he was teaching music theory when he received a call to score an American Film Institute short. It turned out to be the answer to the frustrations he felt as a young classical composer.

“I fell in love with film,” Horner said. “Here was the perfect medium for me. I could be a chameleon. In the serious-music world, if I wrote a very avant-garde piece, it was considered inaccessible. If it had weird wafts of tonality going through it, or offstage waltzes, it was considered reactionary. Movies gave me an excuse to do whatever I wanted so long as it was pertinent to the film.”

By the early ‘80s, Horner was scoring such A-list films as “48 HRS.,” “Gorky Park” and “Cocoon.” In the ‘90s he broadened even further with such diverse assignments as “Patriot Games,” “Searching for Bobby Fischer” and “Legends of the Fall.”

While film-music buffs often delight in taking him to task for repeating himself or borrowing from the classics, Horner considers such criticism an occupational hazard. Similarities to earlier music can be hard to avoid, he said, given the now-common industry practice of “temping” films--using temporary music, often familiar classical or movie cues, for testing and previews--which many directors demand the composer emulate in writing the final score.

“You’re nailed if four notes sound the same as something you’ve done in another film, or the same as somebody else’s four notes,” Horner said. “It’s so difficult to write really original music that still services the film, doesn’t alienate the audience and that sounds new and fresh and different.”

Even after the Grammy Awards are handed out Feb. 24, Horner’s “Titanic” odyssey still won’t be over. Although last year’s scheduled Hollywood Bowl concerts of “Titanic” music were canceled (“It became completely bloated and so expensive to produce”), the composer has agreed to reprise it in three May concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

“We don’t have big sets,” he noted. “It’s now back to being music as opposed to this Hollywood extravaganza. It will be a good experience for me to perform live, which I never do. I’ve always had the safety of the movie studio.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.