Book review: ‘The Hunt for KSM’ is a true thriller

The tale told by former Los Angeles Times reporters Terry McDermott and Josh Meyer in “The Hunt for KSM,” the story of the pursuit, capture and interrogation of Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, mastermind of9/11, at times so resembles something straight out of “24” or the Bourne movies that the authors have to keep reminding the reader that this is for real. On the one hand, “The Hunt for KSM” is a flat-out thriller. On the other, it lays out aspects of our factual contemporary world that are far more ambiguous, internecine and dangerous than anything Hollywood dare contemplate.

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed was born in 1965, in Kuwait, to an immigrant family on the wrong side of the caste system. At school he excelled at science and got the chance to study engineering at a small college in Murfreesboro, N.C. While there he endured minor hazing and began to indulge a hatred of America. In Afghanistan he became an Arab jihadi, fighting to defeat the occupying Soviet army. He was, McDermott and Meyer write, “an adept and relentless networker with a gift for small talk.” He had a reputation as a charmer, and as a prankster. His nephew Ramzi Yousef was behind the first attempt to blow up the World Trade Center in 1993.

This is where tragic irony and huge historical dimension take over what is an otherwise familiar template, that of the smart and angry young man given fanatical purpose by Islamic extremism. FBI agents in the New York field office were tracking KSM from 1993. In Manila, he plotted to assassinate Pope John Paul II and former President Bill Clinton. Another operation involved the simultaneous hijacking of multiple American airliners as they flew over the Pacific. Yet KSM was regarded as a terrorist for hire, not a part of the growing Al Qaeda threat. When9/11 occurred, at first nobody looked in his direction even though he was the mastermind who conceived and orchestrated that terrible attack. The realization of his connection to Al Qaeda didn’t occur until 2002 and was then a moment of drama and almost panic. The president was informed at once, satellites were retasked, and an all-out manhunt ensued.

The search led to teeming Karachi, Pakistan, where American agents suffered from a surfeit of leads. High-tech surveillance and teams of Navy SEALS matter little unless you know where to look, and suddenly the man who’d been nowhere for a decade had a massive bounty on his head and was seemingly everywhere.

“If you were on the ground and asked, you could collect an address for KSM from almost every person you talked to,” the authors write. “He was here in Defence, in a mansion. It was an apartment in Sharifabad, a mud hut in the swamp flats of Korangi, in the Baluch colony of Lyari, in a third-floor walk-up in that Arab neighborhood full of money changers and bucket shops. A man who was arrested had a phone number for Mohammed that was traced to the other end of town, a middle-class preserve and single-family homes with clean modern lines, behind pale stucco walls.”

It didn’t help that the CIA and the FBI were as usual at loggerheads. McDermott and Meyer note, repeatedly and crucially, that the agencies have dueling agendas. Simply put, the CIA’s goal is prevention while the FBI is about investigation and the preparation of cases for trial. Both agencies missed chances to capture Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and perhaps prevent 9/11 and yet, in Pakistan in 2002 and 2003, they were still stepping on each other’s toes. McDermott and Meyer, whose sources come principally from within the FBI, point the finger at CIA intransigence and arrogance.

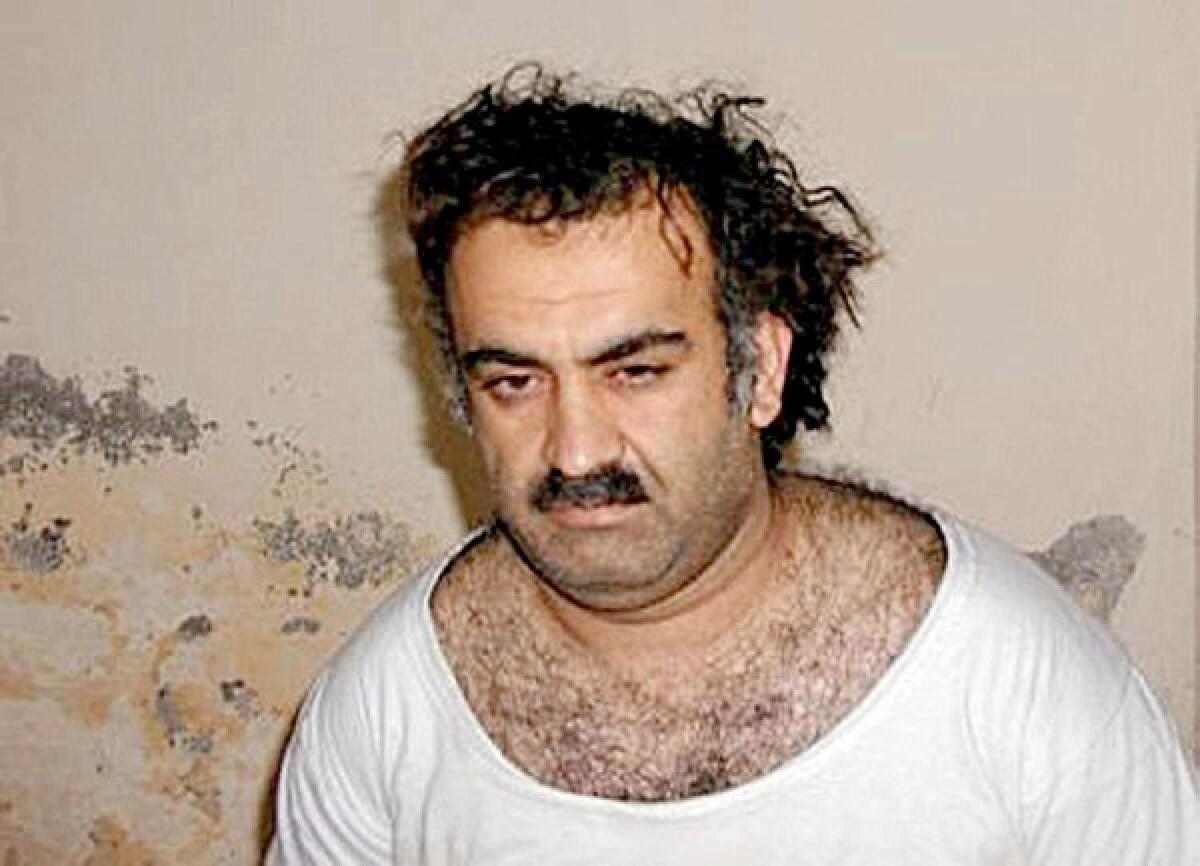

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed evaded capture by lying low, not using electronics, and trusting instead in personal couriers. “He stayed on the ground, in the very human muck that was Pakistan,” write McDermott and Meyer. “So in the end it was almost inevitable that it was a human who would betray him.” The CIA grabbed KSM unawares and in his pajamas.

“KSM was held in Pakistani custody for three days. He was then transferred to U.S. control and taken on a three-year tour of the secret prisons the CIA had established in Asia, Africa, and eastern Europe, most of it blindfolded,” the authors write. Dark arts, indeed: “He was hog-tied, stripped naked, photographed, hooded, beaten, kicked, suffocated, exposed to extreme cold and noise, denied food and sleep, sedated with anal suppositories, placed in diapers, and hung by his wrists until they bled.” When inquisitors threatened to track down his female relatives and have them raped, KSM merely shrugged, “saying, in effect, Really? Is that the best you can do.”

KSM talked, and talked, and talked, and it became apparent to his interrogators that he was talking too much. Some Al Qaeda networks were rolled up, but many leads were false. “He had us chasing the geese in Central Park because he said some of them had explosives stuffed up their ass,” one counterterrorism source told McDermott and Meyer.

Frank Pellegrino, the dogged and quirky FBI guy who had pursued KSM across the globe since the early 1990s and who knew more about him than anybody, was not allowed to go near him until early 2007. The moment seems to come straight out of John le Carre. The antagonists face each other across a government-issue table at Guantanamo and trade stories of near misses. “Pellegrino thought KSM might be the kind of guy you could sit down and have a beer with, if he hadn’t been one of the worst mass murderers in American history,” note McDermott and Meyer.

On Saturday, KSM remained silent at a 13-hour hearing before a military commission in Guantanamo for himself and four other defendants on charges stemming from the Sept. 11 attacks. The charges could carry the death penalty for the five defendants. The hearing came just more than a year after the Obama administration abandoned efforts to try KSM and his co-conspirators before a civilian court.

Investigators believe parts of KSM’s networks remain in place, waiting for another day. As McDermott and Meyer point out, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed’s hovering presence and the long uncertainty about what to do with him have become metaphors for our general anxiety concerning the war with Islamic terrorism. We wish it was over; we know it isn’t.

Rayner is the author, most recently, of “A Bright and Guilty Place: Murder, Corruption, and L.A.’s Scandalous Coming of Age.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.