Hedy Lamarr: Hollywood’s bombshell inventor is subject of new documentary

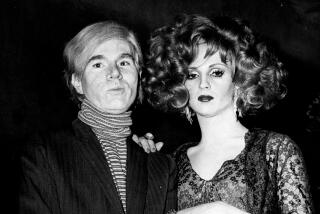

Hedy Lamarr was, to use the old studio lingo, a bombshell, one of the most glamorous stars of the Golden Age of Hollywood. But that’s only part of her story.

She was also a groundbreaking inventor whose work was used by the military and later led to the development of wireless technology used in cell phones and the internet.

When she was dating Howard Hughes, the Austrian actress created designs to simplify his airplanes. And at the beginning of World War II, she and avant-garde composer George Antheil received a patent for a “frequency hopping” device that manipulated radio frequencies.

The U.S. Navy ignored the patent and Lamarr and Antheil never received any payment. After the patent ran out, it was used by the military during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. In 1997, Lamarr and Antheil, who died in 1959, received the Electronic Foundation Pioneer Award. The two were inducted posthumously into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

The technology they helped develop became the basis for such wireless operations as cell phones, GPS and fax machines.

“My mother was very bright minded,” said her son, Anthony Loder. “She always had solutions. Anytime someone complained about anything, boom, her mind came up with a solution.”

The actress, who died in 2000 at 85, is the subject of a new documentary “Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story,” which opens Friday. The documentary features interviews with Mel Brooks, the late Robert Osborne, director Peter Bogdanovich, actress Diane Kruger and author Richard Rhodes, who wrote the acclaimed book “Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World.”

Rhodes’ book inspired writer-director Alexandra Dean and producer Adam Haggiag to make “Bombshell.” Dean, who covered innovation and technology for Bloomberg Television and Businessweek, was troubled that she profiled very few women. As Dean puts it, “I was looking for a ‘Hidden Figures’ character.”

Her colleague, producer Katherine, Drew was on a panel with Rhodes and then brought the book to the attention of Dean and Haggiag.

Despite the book, “A lot of scientists we were talking to at the beginning of researching this were saying ‘Well, it’s really a nice rumor, but really, she did steal it,” said Dean, who noted that they believed she got the idea from her first husband, Austrian munitions manufacturer Friedrich Mandl.

So the filmmakers wanted further confirmation. Enter writer Fleming Meeks who interviewed Lamarr in 1990 for Forbes magazine.

“I got a call and the person on the line asked me if I have any memories from writing this article, if I had any notes or whatever,” recalled Meeks. “Well, I have the tapes of all of my interviews. A day or two later, I went down to their office and just handed them over. When I went in to first meet them, I said I’ve been waiting 25 years for you to call me. This is what I wanted. I wanted someone who could use them.”

In those tapes, Lamarr talked about her inventions, though she often jumped around in the conversation from topic to topic.

“You had to construct these complete thoughts from these fragments,” Dean explained. “But when you did, that would get us something that was this whole portrait, which was really fascinating. It was like a mirror had been broken and you had to reassemble each piece.”

Scientific inventions were only part of Lamarr’s complicated and often tragic life. She was born Hedwig Eva Marie Kiesler in Vienna in 1914 to Jewish parents. She became an actress and caused a scandal when she appeared naked in the 1933 film “Ecstasy.” She later married Mandl, who was connected with the Nazis and controlled her with an iron hand.

She fled the marriage, eventually making her way to London where she met MGM head Louis B. Mayer. She signed a contract before making her American debut in the 1938 drama “Algiers.” She went on to star in many films including the 1949 Biblical story “Samson and Delilah.”

But despite her success and remarkable beauty, Lamarr led an increasingly sad and lonely life, as the documentary portrays. She was married six times and denied her Jewish heritage. She became dependent on drugs, which turned her into a monster especially with her children. Loder recalls in the movie that Lamarr hit him in the face because he didn’t pick up something she dropped.

Lamarr’s daughter Denise Loder DeLuca said her mother mentioned the patent to her, but “it would just seem so bizarre to me that I just didn’t get it,” said DeLuca. “It just seemed so out of the blue to me.”

DeLuca also didn’t know she had Jewish roots. “I would call Mom at the end of her life and say, ‘People keep telling me we’re Jewish. And she would literally say ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’”

Dean made four trips from New York to visit Loder in Los Angeles to peruse his mother’s archives. Dean discovered evidence in documents and letters from Lamarr to her mother that the actress was indeed Jewish.

As she got older, Lamarr became obsessed with plastic surgery to the point she no longer looked like herself. She became a recluse, only talking to her children on the phone and sending her grandchildren autographed pictures.

DeLuca remembers the last time she saw her mother in New York. “She was in her late 70s. I hadn’t see her in forever and we took her out to dinner. She didn’t look like Hedy Lamarr, but she looked so chic. She had presence. Somebody came up to her on the sidewalk and said, ‘I don’t know who you are, but you must be somebody.’ I loved that.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.