Surprisingly candid Bob Dylan, AARP magazine cover boy

Like many great artists, Bob Dylan has made a career and reputation out of playing with ambiguities. After all, we are talking about a man who told an entire generation that the answers to many of life’s vexing questions were blowing in the wind but famously never provided the answers.

In May, Dylan hinted through his website (cryptically, though, through a sneak YouTube release of a single track and an image that was interpreted as an album cover) that in early 2015 he would be releasing an album of songs made famous by Frank Sinatra.

The album, “Shadows in the Night,” finally will come out on Feb. 3. And as has become customary with new Dylan releases, the singer carefully selected only a couple of outlets to talk about the project. Over the past few years he usually chose publications like Rolling Stone magazine or Newsweek, and occasionally he has even published exclusive interviews with friends and associates through his own website.

This time around, however, Dylan chose to talk to AARP magazine, which promotes itself as “the world’s largest-circulation magazine, with more than 47 million readers.” (Though Robert Love, the editor in chief of the magazine who conducted the interview, tells Dylan it’s more like 35 million readers. In any case, it’s a lot of readers.)

Dylan appears on the cover of the February/March 2015 issue, and the interview he gave Love is more insightful and candid than many of his recent encounters with the press. To put it in perspective, Dylan’s 2012 interview with Rolling Stone’s Mikal Gilmore to promote the “Tempest” album degenerated into a bizarre exchange about the singer transforming into a dead Hell’s Angel also named Bobby Zimmerman and in the end calling his critics “wussies and pussies.”

Here are some of the highlights of Dylan’s AARP interview, which is worth reading in full:

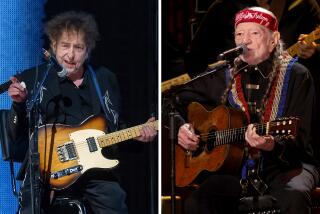

On the record that inspired “Shadows in the Night”: “I’ve been thinking about it ever since I heard Willie [Nelson]’s ‘Stardust’ record in the late 1970s. All through the years, I’ve heard these songs being recorded by other people and I’ve always wanted to do that. And I wondered if anybody else saw it the way I did.”

On Sinatra’s influence: “When you start doing these songs, Frank’s got to be on your mind. Because he is the mountain. That’s the mountain you have to climb, even if you only get part of the way there. [...] He had this ability to get inside of the song in a sort of a conversational way. Frank sang to you — not at you. I never wanted to be a singer that sings at somebody. I’ve always wanted to sing to somebody.”

On his crush on the Staple Singers’ Mavis Staples: “I remember listening to the Staple Singers, ‘Uncloudy Day.’ And it was the most mysterious thing I’d ever heard. It was like the fog rolling in. What was that? How do you make that? It just went through me. I managed to get an LP, and I’m like, ‘Man!’ I looked at the cover, and I knew who Mavis was without having to be told. She looked to be about the same age as me. Her singing just knocked me out. This was before folk music had ever entered my life. [...] I said to myself, ‘One day you’ll be standing there with your arm around that girl.’ I remember thinking that. Ten years later, there I was — with my arm around her.”

On whatever happened to the rock ‘n’ roll revolution of the 1950s: “There must have been some elitist power that had to get rid of all these guys, to strike down rock ’n’ roll for what it was and what it represented — not least of all it being a black-and-white thing. [...] That was extremely threatening for the city fathers, I would think. When they finally recognized what it was, they had to dismantle it, which they did, starting with payola scandals. The black element was turned into soul music, and the white element was turned into English pop. They separated it. I think of rock ’n’ roll as a combination of country blues and swing band music, not Chicago blues, and modern pop. Real rock ’n’ roll hasn’t existed since when? 1961, 1962? Well, it was a part of my DNA, so it never disappeared from me. I just incorporated it into other aspects of what I was doing.”

On how people should obtain Dylan’s music in the 21st century: “The business end of the record — it’s none of my business. I sure hope it sells, and I would like people to listen to it. But the way people listen to music has changed, and I hope they get a chance to hear all the songs in one way or another. [...] If it was up to me, I’d give you the records for nothing and you give them to every [reader of your] magazine.”

On the permanence of standards vs. his own 1960s material: “A song like ‘I’m a Fool to Want You’ — I know that song. I can sing that song. I’ve felt every word in that song. I mean, I know that song. It’s like I wrote it. It’s easier for me to sing that song than it is to sing ‘Won’t you come see me, Queen Jane.’ At one time that wouldn’t have been so. But now it is. Because ‘Queen Jane’ might be a little bit outdated. But this song is not outdated. It has to do with human emotion. There’s nothing contrived in these songs. There’s not one false word in any of them. They’re eternal.”

Follow me: @eyecantina

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.