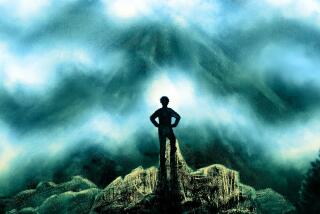

‘In the Valley of the Kings’ by Terrence Holt

Geographically, Terrence Holt’s debut collection could hardly be more expansive. The seven stories and one novella that constitute “In the Valley of the Kings” take the entire solar system for their canvas. And yet, whether set in the Egyptian desert or upstate New York, on a spaceship orbiting Jupiter or a different craft circling Saturn, each of these stories is animated by the same force: a human desolation so profound that Holt seems hard-pressed to find locations barren enough to match it.

The universe of Holt’s fiction is sparsely populated -- necessarily so, it would seem, since confronting the terror of solitude and grasping at flickering memories of an elusive past is how most of his characters spend most of their time. Of these eight pieces, only the final one, “Apocalypse,” is built around an attempted emotional connection between two people: a married couple whose final months on a doomed Earth are complicated by their distance from each other.

Otherwise, the primary intercourse in these stories is between men and longing, men and memory, men and death. Holt is a gifted wordsmith, his sentences carefully shaped and often beautiful, and he spins these ancient, unresolvable dilemmas into an elegiac poetry.

All are told in the first person, many by characters who face imminent demise and strive to leave some final record: a plague survivor, an Egyptologist trapped in a tomb, a damned astronaut, a disembodied mind tethered to a spaceship. At their best, these accounts achieve a kind of hypnotic rhythm, rich in interior detail.

In “Charybdis,” the last astronaut aboard a failed expedition to Jupiter chooses to tune out mission control -- his only contact, his only hope. The story is a kaleidoscope of memory, space and dream, as the narrator communes with a planet that “speaks syllables, sibilants, subsides. I no longer need to direct the antenna: the sound seems to pierce the cabin walls, rising from the chaos below.”

“Scylla” trades Holt’s tendency to send his protagonists floating toward oblivion for an opposite conceit: A sea captain returns home to find that a mysterious concept called Law is remaking the world, bringing order and domesticity where the freedom of open waters once reigned. Though he succumbs to it, feeling “the weakening of my resolve, the strength of my limbs draining away,” the captain remains an outsider, a dreamer, to the bitter end, living in the faint hope that the world may change back, the ocean may restore his vanished ship to him.

In the first story, a deadly plague spread by the reading of a certain word has decimated humanity. Although it is less a story than an idea masquerading as one, Holt riffs with enough wit and intelligence to make it work. The same is true of “My Father’s Heart,” the macabre tale of a man bullied by an organ that lives in a jar on his mantelpiece.

Though Holt’s imagination is impressive, “In the Valley of the Kings” imposes a kind of fatigue on the reader. The author returns to similar themes and motifs so frequently that his characters and their dilemmas begin to blur. The elusiveness of language is one such idea; throughout this collection, characters grasp after words, struggle to name the objects in the strange worlds they inhabit, suspect the trickery of text.

From “Aurora,” about a human consciousness trapped in an ice-gathering spaceship: “I call it burning. I call it ice. I call it emptiness, falling, silence, dark . . . . I conjure it with names, with images, fragments of memory, of desire: wind, and a flying fire. I call it smoke. None of these answers.”

In “Eurydike,” the story of an man who awakens in an empty compound, and solves the mystery of his existence, he writes: “Words float up on a cold whisper in me -- island, realm, domain -- but on the screen I see only wave after featureless wave . . . .”

From “In the Valley of the Kings,” in which an obsessed archaeologist’s quest for immortality ends tragically: “[A] voice was speaking, close in my ear, a word whose syllables I might almost recall. But what the word, and whence the voice, I cannot say.”

From “Charybdis”: “I have caught myself calling back earlier pages . . . to see if the text has been altered. . . . I am tantalized by a suspicion -- surely that word was not noses, but something starting with a g; and that was cave, not save.”

The repetition of this trope, despite the artfulness of Holt’s sentences, serves to deaden the impact of his stories.

Pacing is a related problem. Many of these pieces plod when they should race; dramatic tensions remain stable when they ought to build. The unrelenting interiority of Holt’s narrators often prevents this from happening; set on chronicling their doom, they write with a deliberateness that at times cries out for posthumous editing. Particularly affected are stories like “Eurydike” and “In the Valley of the Kings,” which climax in action and revelation; they simply are not built to support such moments. But when Holt is at his bleak, elegant best, “In the Valley of the Kings” offers considerable rewards.

Mansbach is the author of “The End of the Jews,” winner of the California Book Award.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.