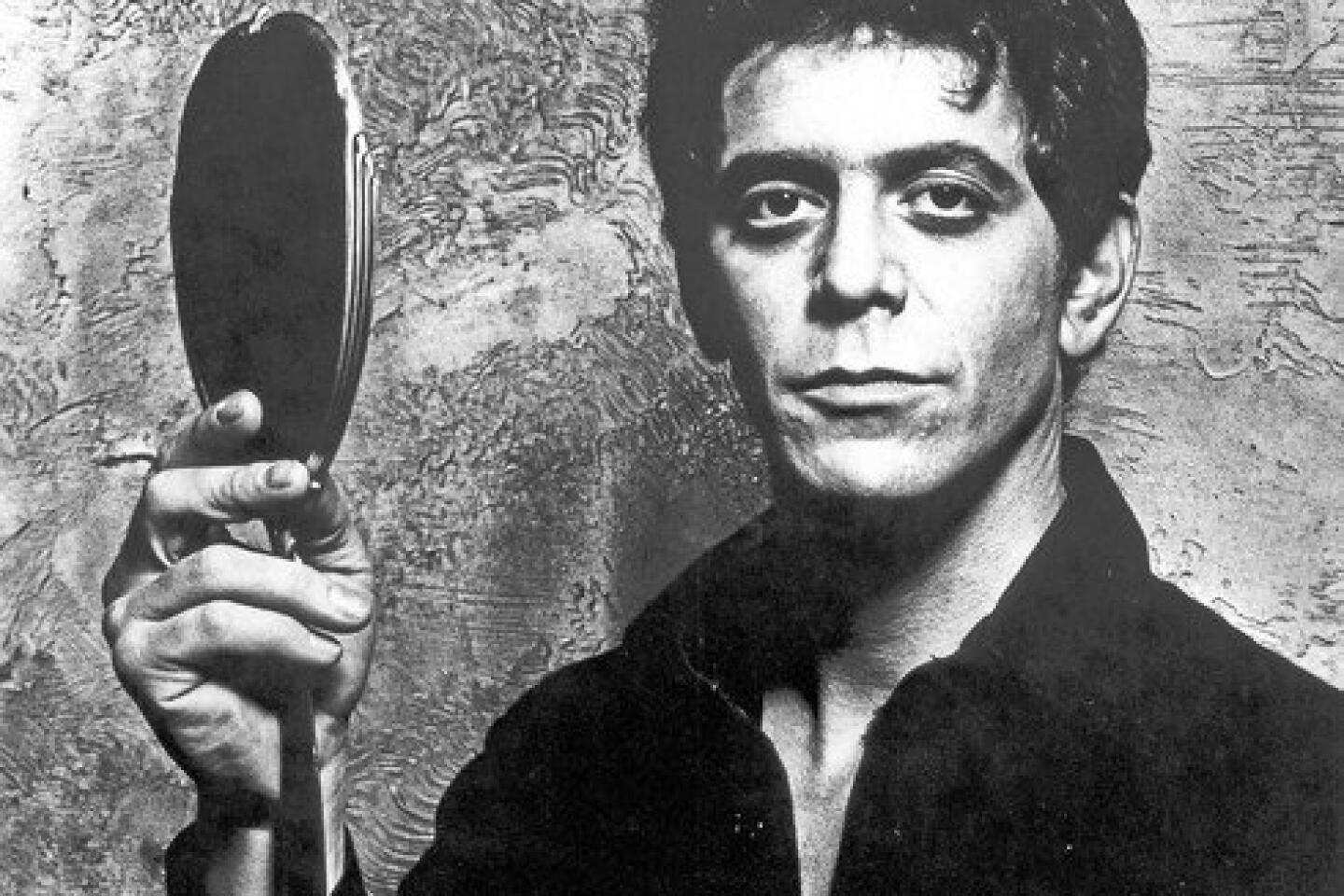

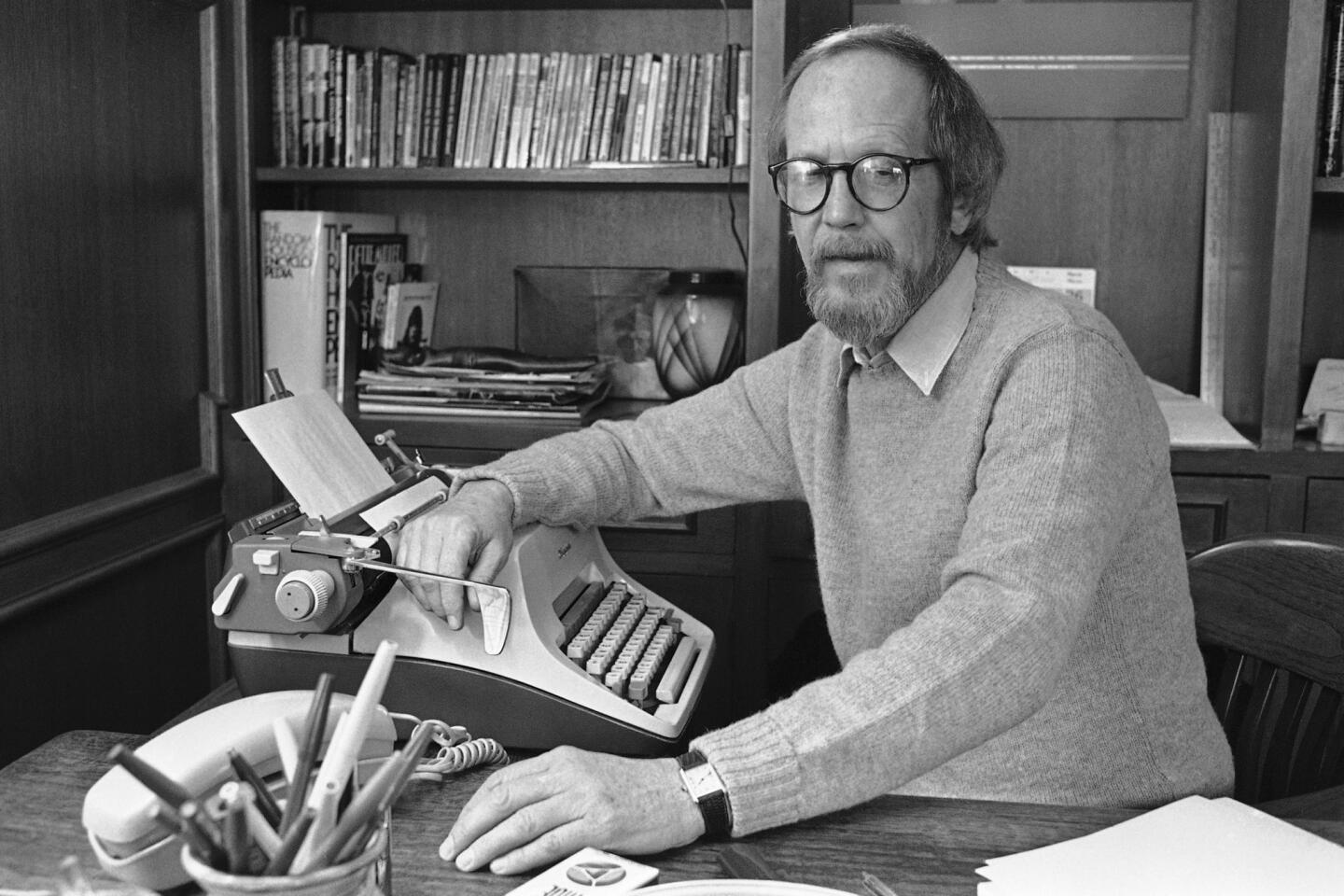

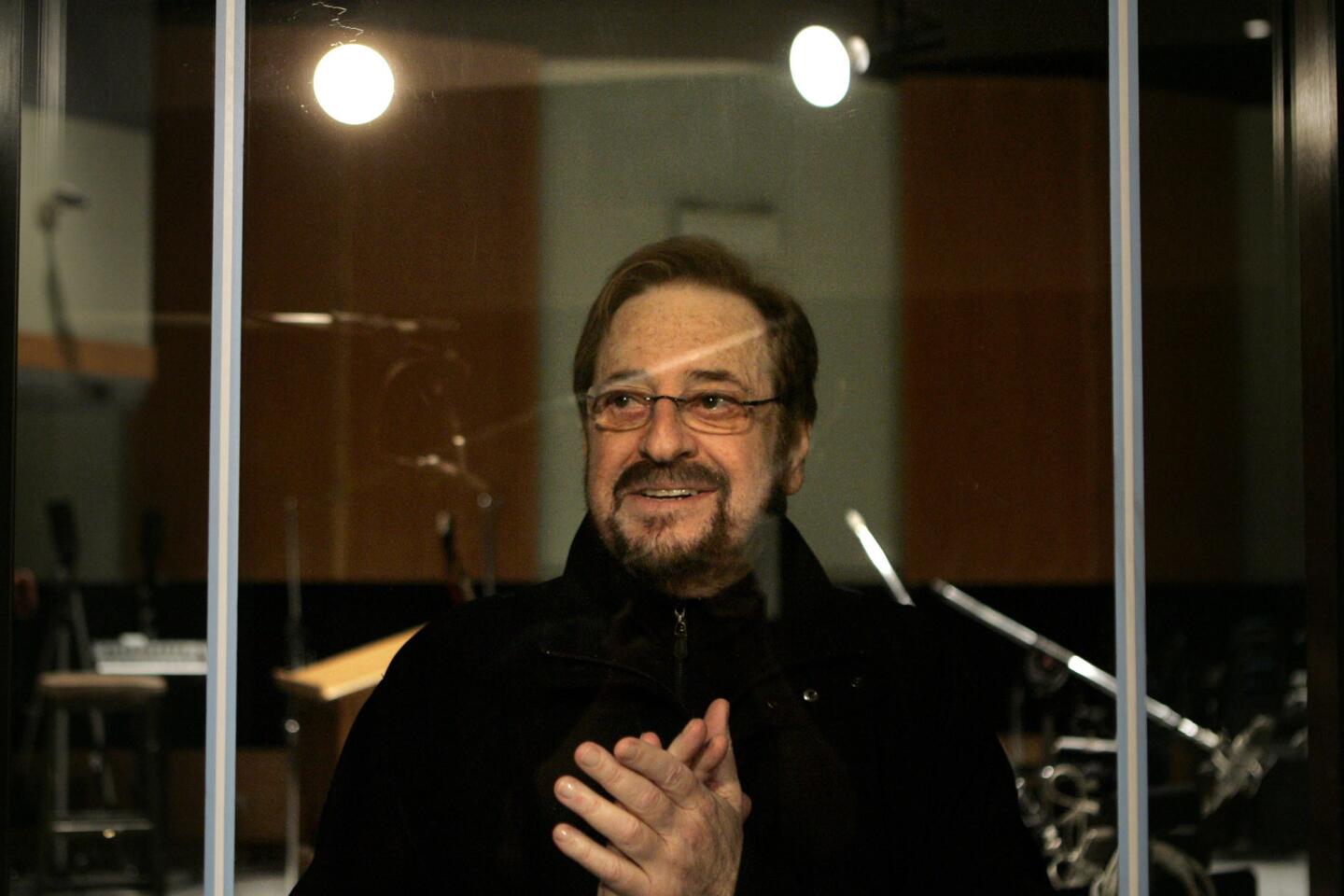

Alvin Lee dies at 68; guitar virtuoso with Ten Years After

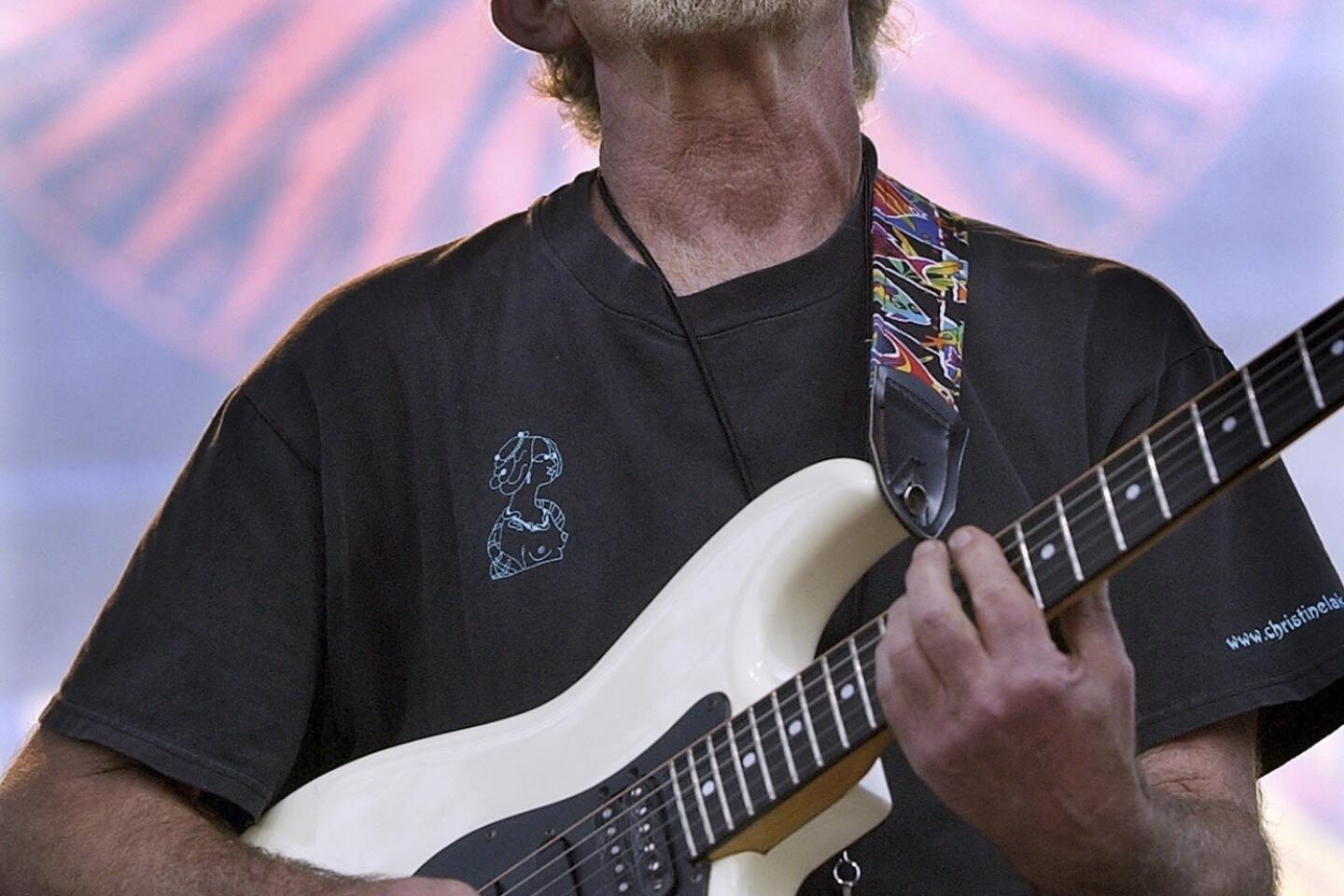

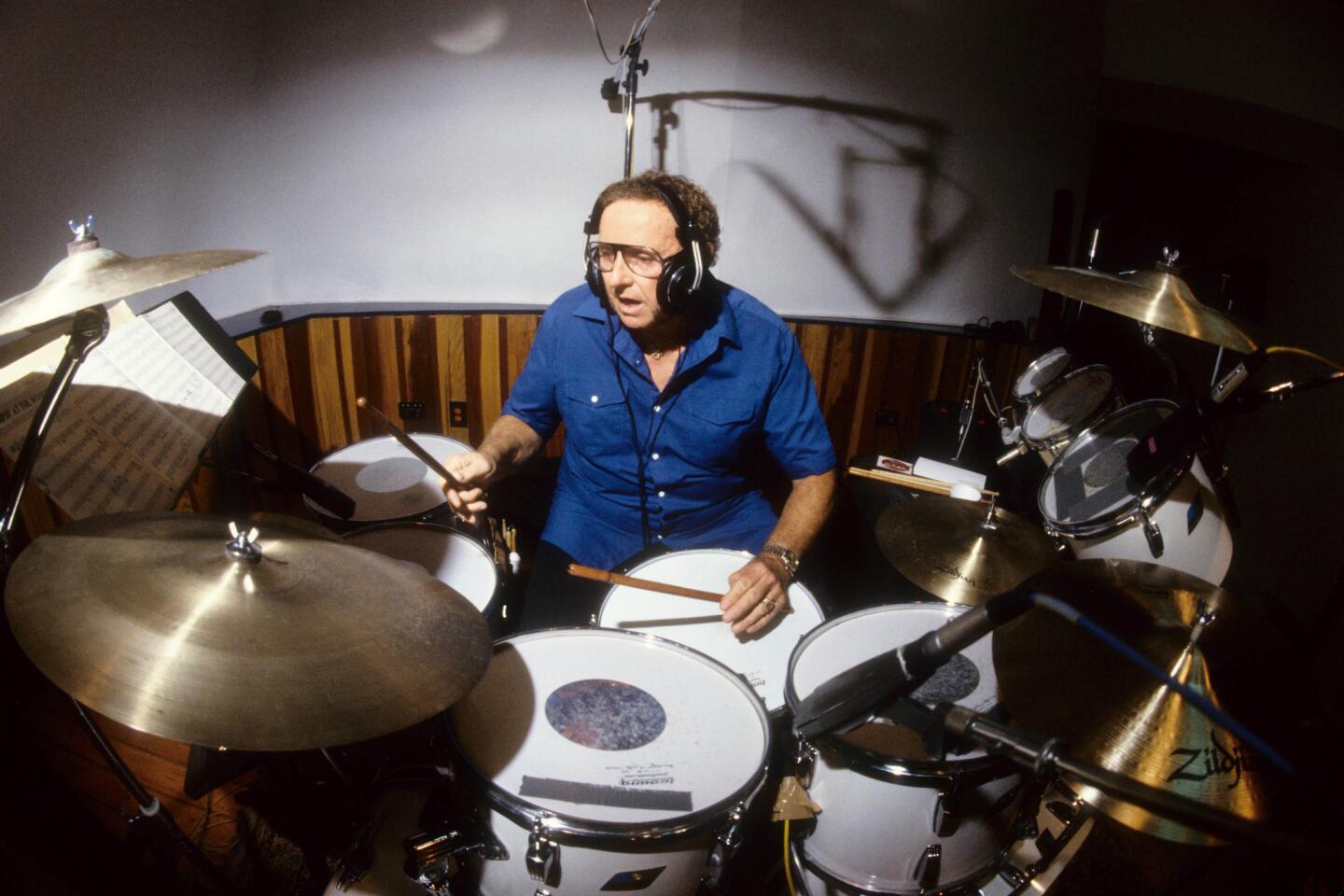

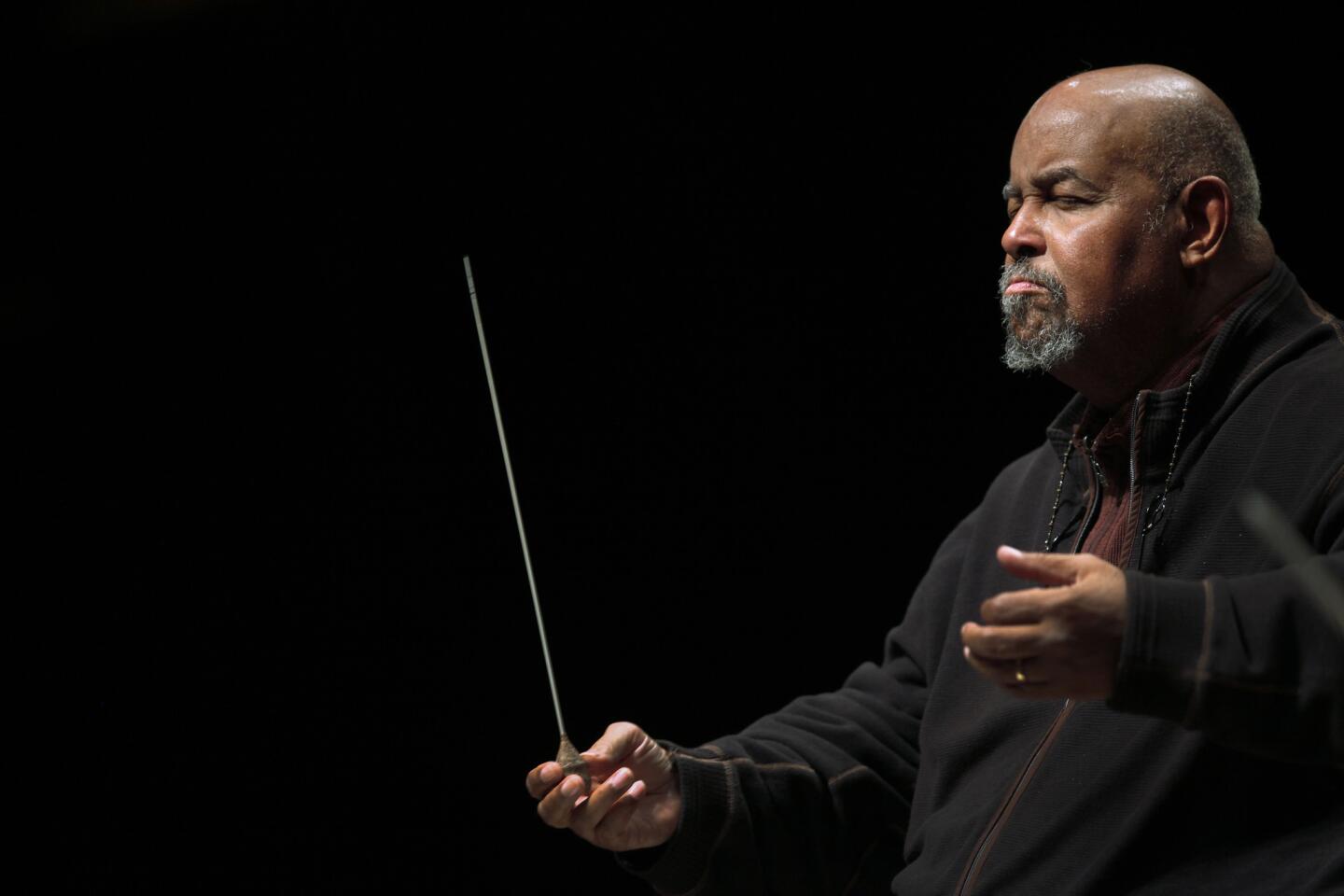

At the Woodstock music festival in 1969, the British blues-rock band Ten Years After burst onto the U.S. music scene with a searing rendition of “I’m Going Home” featuring the fleet-fingered Alvin Lee whaling away on guitar.

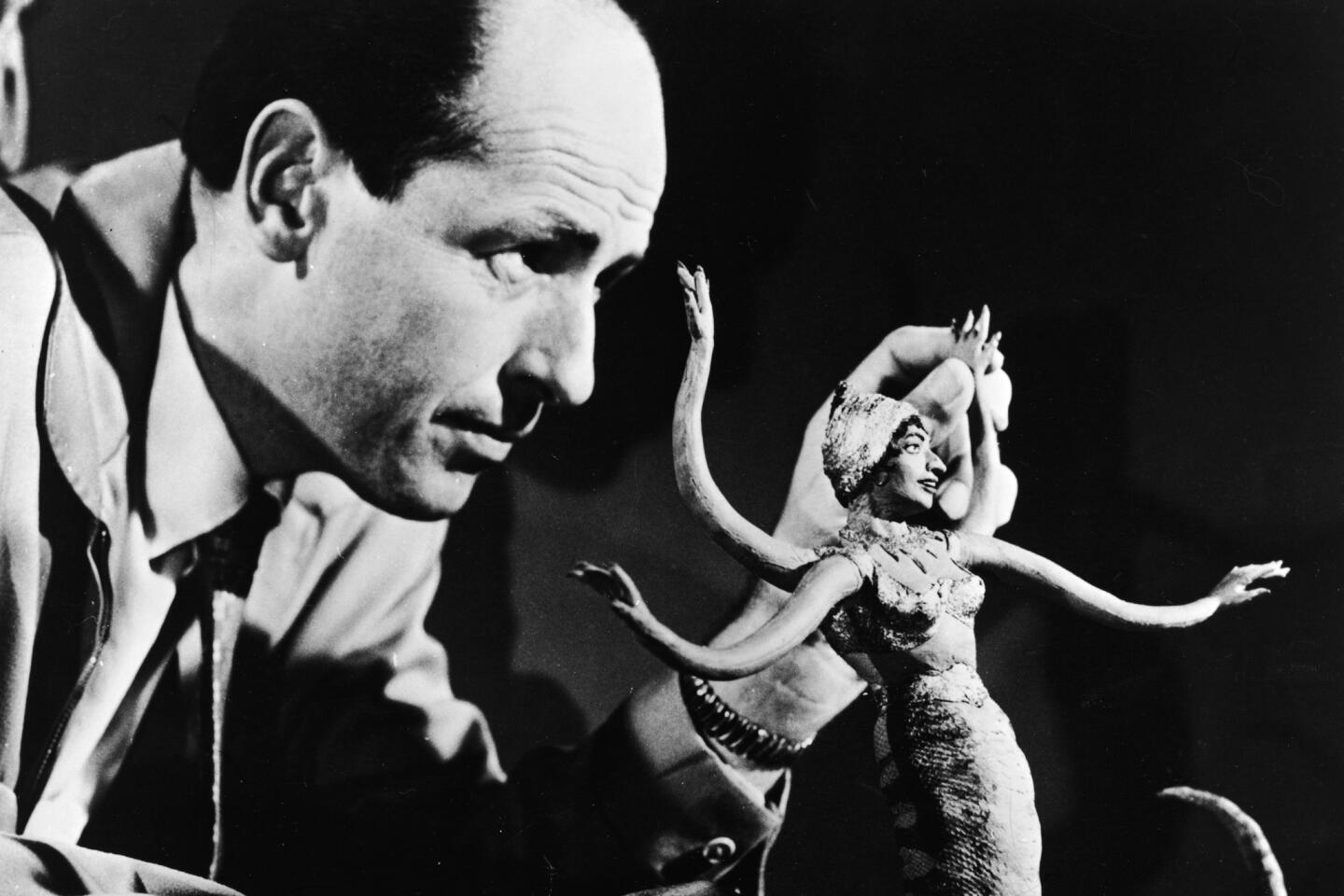

When the “Woodstock” documentary was released the next year, the band’s 11-minute version of the song — and Lee’s guitar virtuosity — were regarded as a highlight. His speedy, taut playing would earn him the unofficial title of “the fastest guitar in the West.”

Lee, who also was a singer-songwriter and later pursued a solo career, died Wednesday in Spain following complications from routine surgery, said his manager, Ron Rainey. He was 68.

The “Woodstock” movie also marked the beginning of the end for Ten Years After.

Sudden fame from the film meant jumping from cozy performances in clubs to big arenas and the band started sounding like a “traveling jukebox,” Lee said as early as 1973.

“We sort of auditorium-alized” was how Lee once put it as he explained the stylistic move away from the group’s British blues-jazz-rock roots.

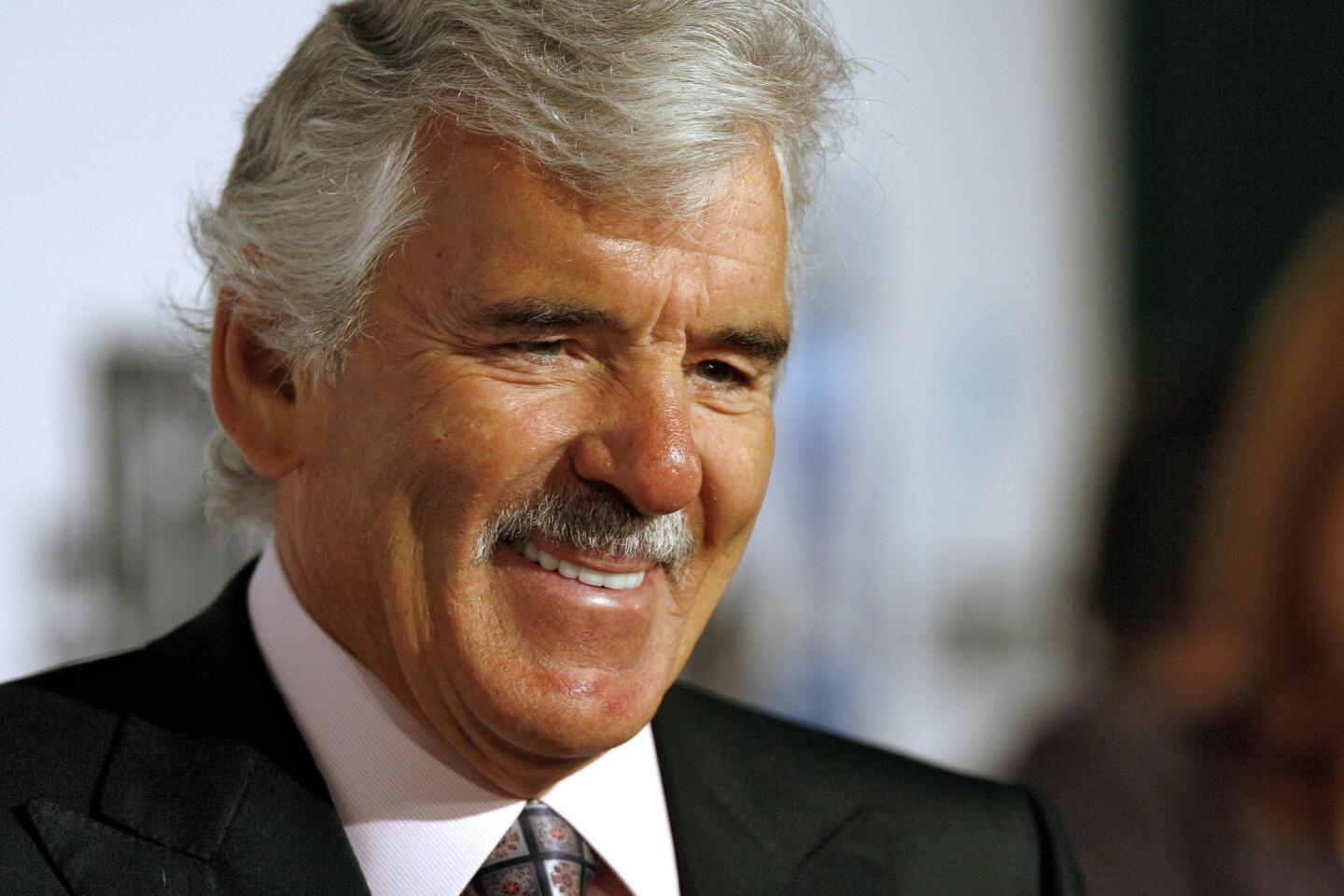

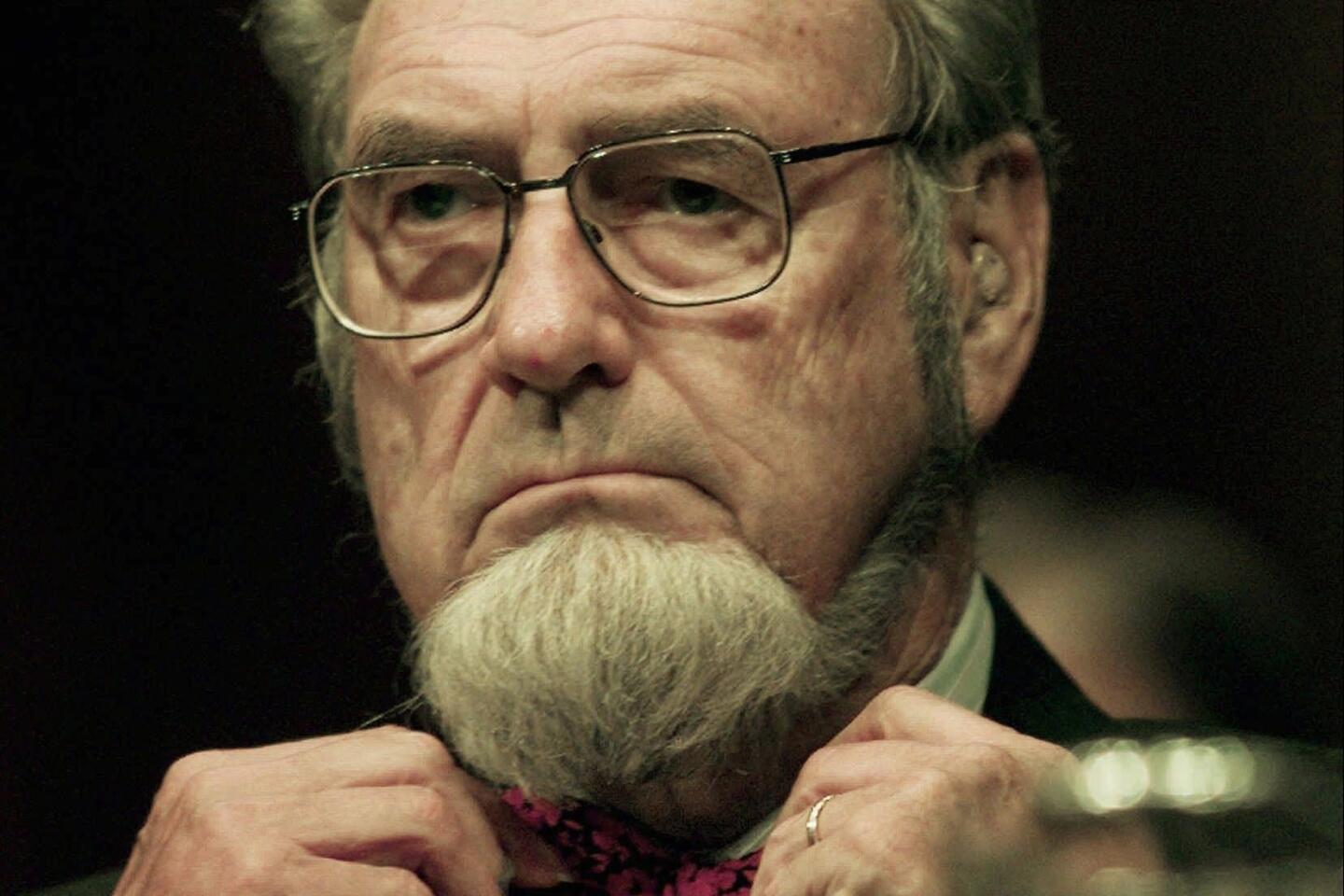

“When they changed to a harder rock sound, they left a bit of their creativity behind,” said Domenic Priore, coauthor of the 1960s music history “Riot on Sunset Strip” (2007).

Depending on the point of view, Ten Years After’s impassioned performance in the “Woodstock” film is either seen as a watershed moment for hard rock or “the ultimate example of the self-indulgence of classic rock” because the song goes on and on, Priore said Wednesday.

The band’s other well-known songs include 1970’s “Love Like a Man” and 1971’s “I’d Love to Change the World,” which received renewed attention when it was used in Michael Moore’s 2004 documentary “Fahrenheit 9/11.”

After releasing the album “Positive Vibrations” in 1974, the band split up. “We were overworked and overpaid,” Lee said in 1998 in USA Today, and “got tired and fell apart.”

Drug use was also a factor, Lee once told the Nottingham Post. He had purchased a mansion with a recording studio but constant partying ruined most of the private recording sessions.

Following a stint in rehab, Lee emerged to pursue a solo career. He collaborated with such artists as George Harrison and Mick Fleetwood on 1973’s “On the Road to Freedom,” which featured vocals by Mylon LeFevre. Last fall, Lee released what would be his final album, “Still on the Road to Freedom.”

Over the years, Lee reunited with Ten Years After and performed with them as recently as 2000, according to his manager. The other original members of the quartet — keyboardist Chick Churchill, bass guitarist Leo Lyons and drummer Ric Lee — continue to tour as Ten Years After with another guitarist.

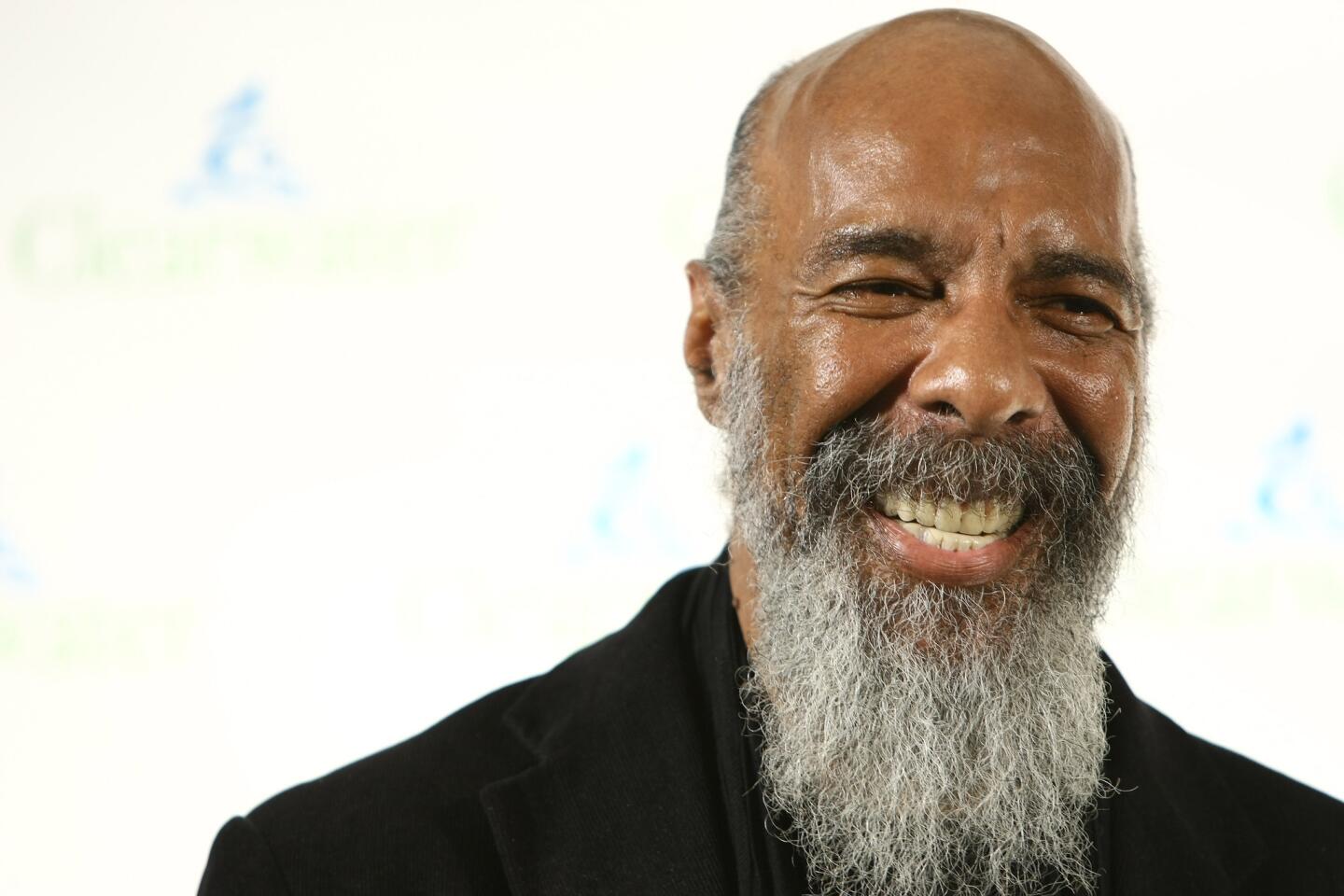

On Wednesday, Lyons called Lee “an inspiration for a generation of guitar players.”

“He was the closest thing I had to a brother,” Lyons told The Times in an email. “We had our differences but we shared so many great experiences together that nothing can take away.”

Lee was “a real leader of men,” Churchill said in a separate email. “When I first saw him play it became my ambition to play with him.”

The guitarist was born Graham Alvin Lee on Dec. 9, 1944, in Nottingham, England. His father, Sam, was a builder who collected jazz and blues records, and his mother, Doris, was a hairdresser.

At age 12, Alvin had a year of clarinet lessons behind him when American blues singer-guitarist Big Bill Broonzy came to the Lee house after a concert and held court. From then on “blues was in my heart,” Lee told The Times in 1994, and he took up guitar.

As Alvin Lee and His Amazing Talking Guitar, he made his debut as a professional musician at 13 at a regular gig at a movie theater.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, he played with several bands before forming the Jaybirds, a beat trio that expanded to become Ten Years After around 1966. They settled on the name after seeing the phrase “ten years after” in a local radio listing.

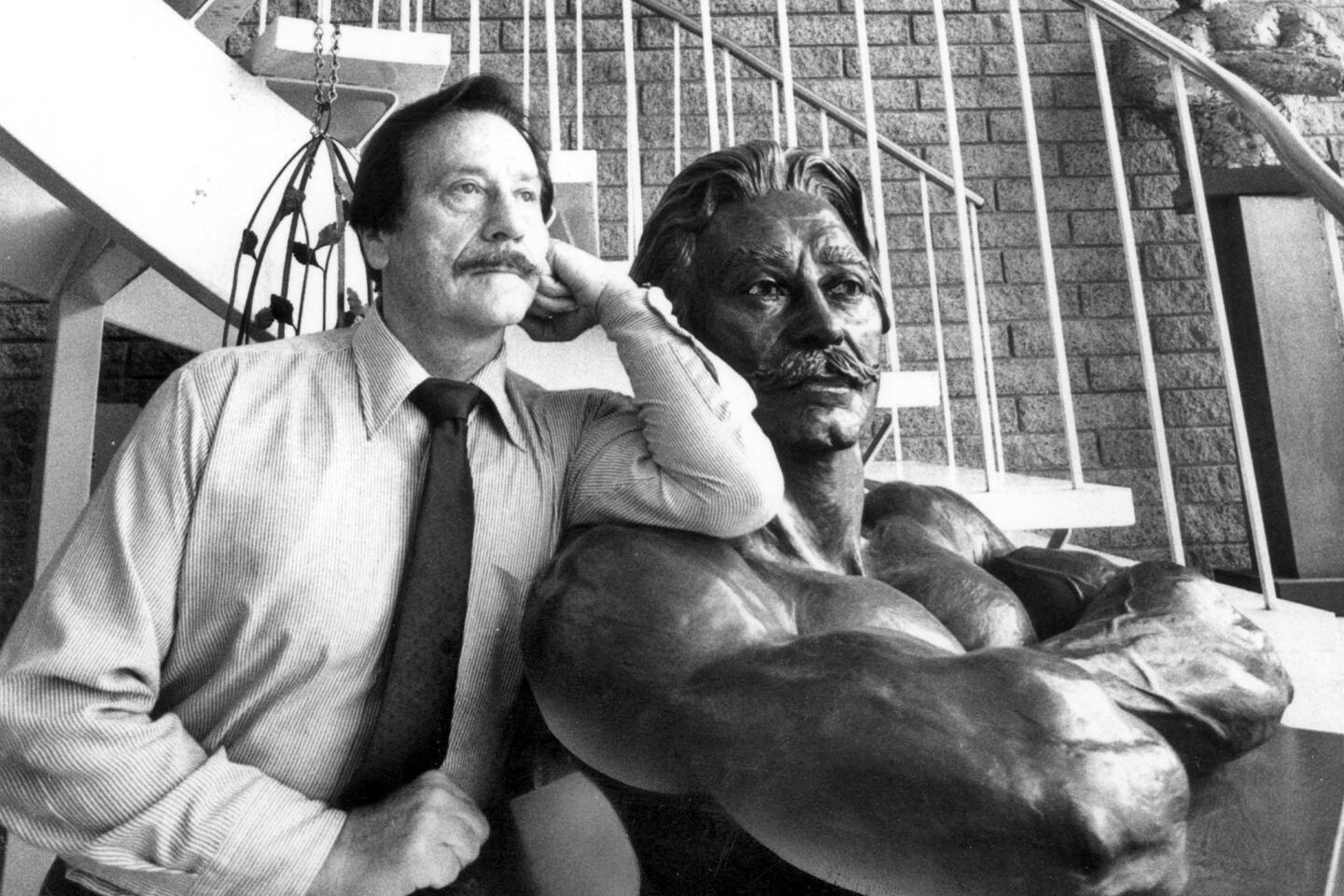

When the band performed at the Long Beach Arena in 1975, Times reviewer Richard Cromelin called Lee “that hulking encyclopedia of ‘60s electric blues, riffs, fills and solos.”

For many years, he had lived in Spain and toured sparingly. Lee had a sold-out show booked in Paris for the end of March and talked about recording a blues album with musicians in the U.S.

He had “always wanted to be a musician, a working musician, not a rock star,” Lee said in the 1994 Times interview. “It’s really all I know how to do.”

His survivors include his wife, Evi, and a daughter, Jasmin, from a previous relationship.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.