Dee Rees gave ‘Mudbound’ a personal touch with the help of her grandmother’s journal

For black folks, writing down our family histories is often a foreign concept. After all, because many of our enslaved ancestors could not read and write, they orally passed on legacies, using spoken word to maintain a connection to their homeland. Today, though literacy has drastically increased, such an oral tradition persists, at family reunions and around kitchen tables.

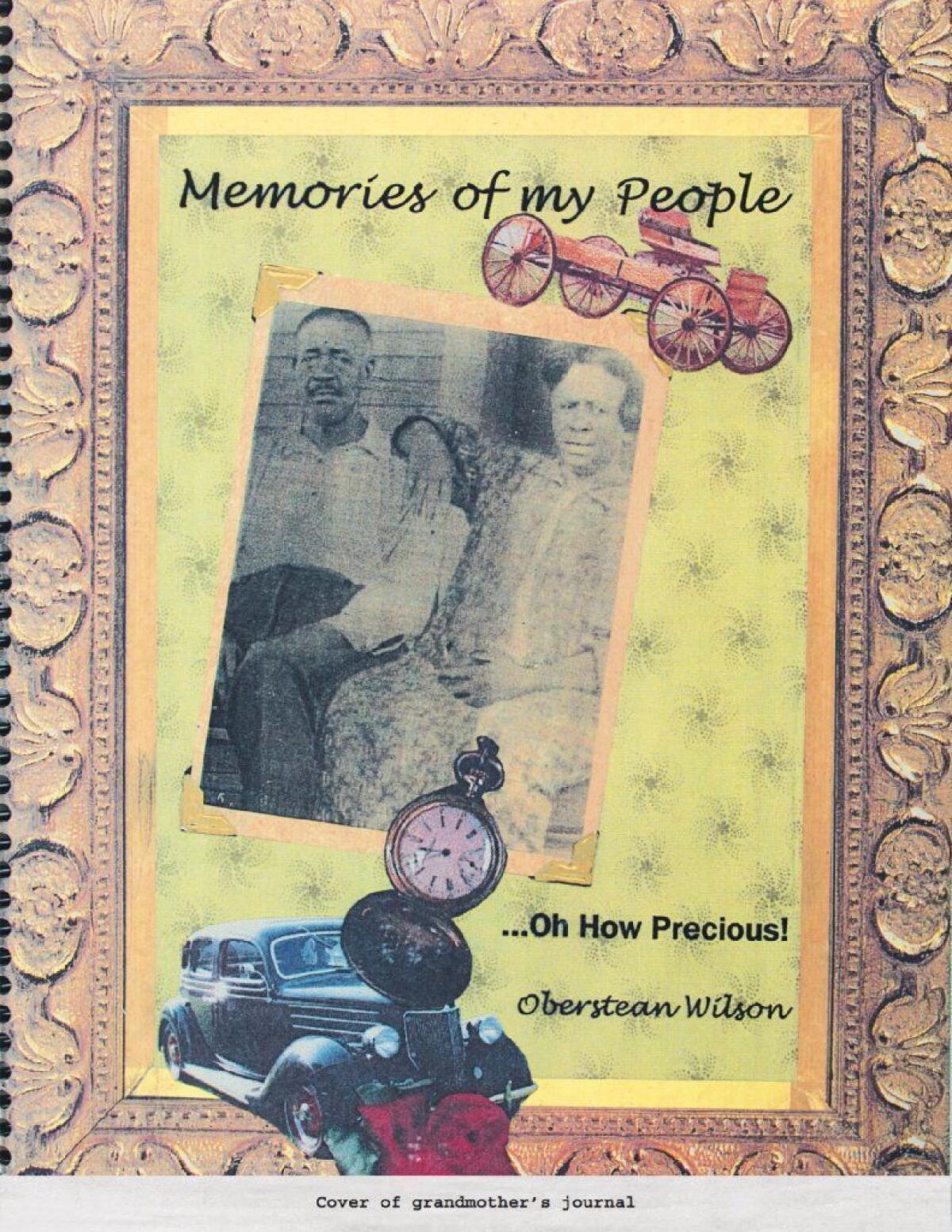

But for Earnestine Smith, grandmother of writer-director Dee Rees, making her family's history tangible, in the form of a journal she titled “Memories of My People,” was important.

Because if you don’t know from where you come, you don’t know how far you can go.

“My grandmother did the thing that I’m not doing and my mother isn’t doing,” said Rees.

Years later, however, Smith’s effort has even greater use than potentially intended. Her journal became a significant reference and inspiration for Rees’ latest film “Mudbound,” in theaters and available on Netflix on Nov. 17. “It just really let me own the story and be like ‘Yeah, I can tell this and I’m allowed into this narrative,’” she said.

“Mudbound” is a tale about two families connected by land. The Jacksons are black sharecroppers who claim an ancestral connection to the soil they till, while the McAllans are white, middle class and bought their their way in. Each family has someone in it that has just returned from World War II to rural Mississippi and must deal with racism and adjusting to life after war. The ensemble cast includes Mary J. Blige, Rob Morgan, Jason Mitchell,

The initial script, written by Virgil Williams (“Criminal Minds”), came to Rees in 2015. While she admitted that she never likes any script that she reads, she noted that Williams’ script piqued her interest to check out Hillary Jordan’s 2008 book it was based on. She decided that if she was going to sign onto the project, “I had to make this a story that would be interesting for me to tell.”

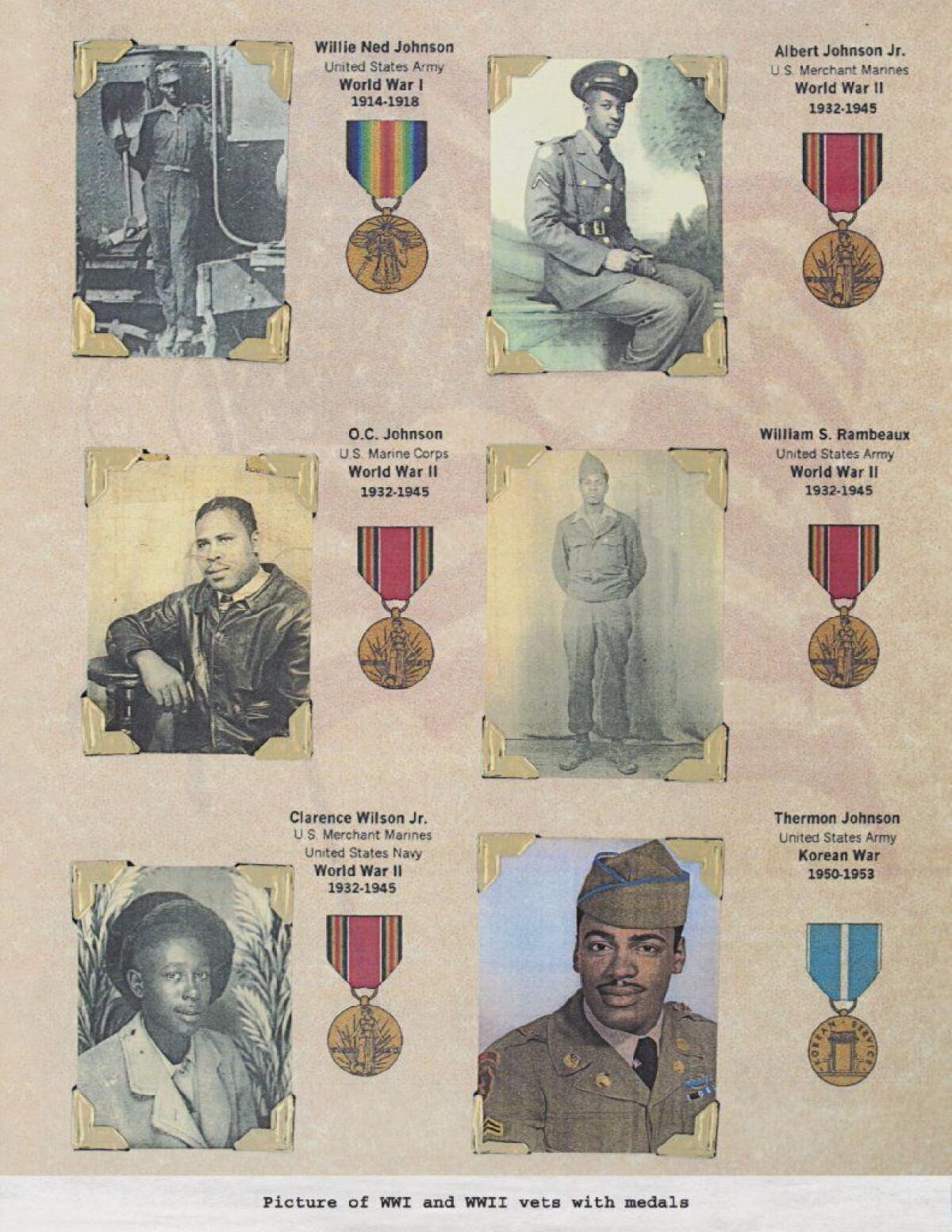

Enter her grandmother’s journal. In its hundreds of pages is everything from family photos of their slave ancestors to the names, ranks and medals of relatives who fought in wars, to floorplans of Smith’s childhood homes.

“It was a shameless excuse to go back and inject this into the story,” the “Pariah” and “Bessie” writer-director said. “It was a way of interrogating my own personal history and it gave me license to make the Jacksons anew.”

“And this is a period that gets skipped over,” she added. “We go straight from slavery to Civil Rights. I wanted to explore what’s in there.”

Rees’ first task was to build out some of the characters.

“I wanted the characterizations to be rounded and honest and I wanted the Jackson family to have their own agency and ideas and not just serve the McAllans,” she said.

FULL COVERAGE: Holiday movie preview »

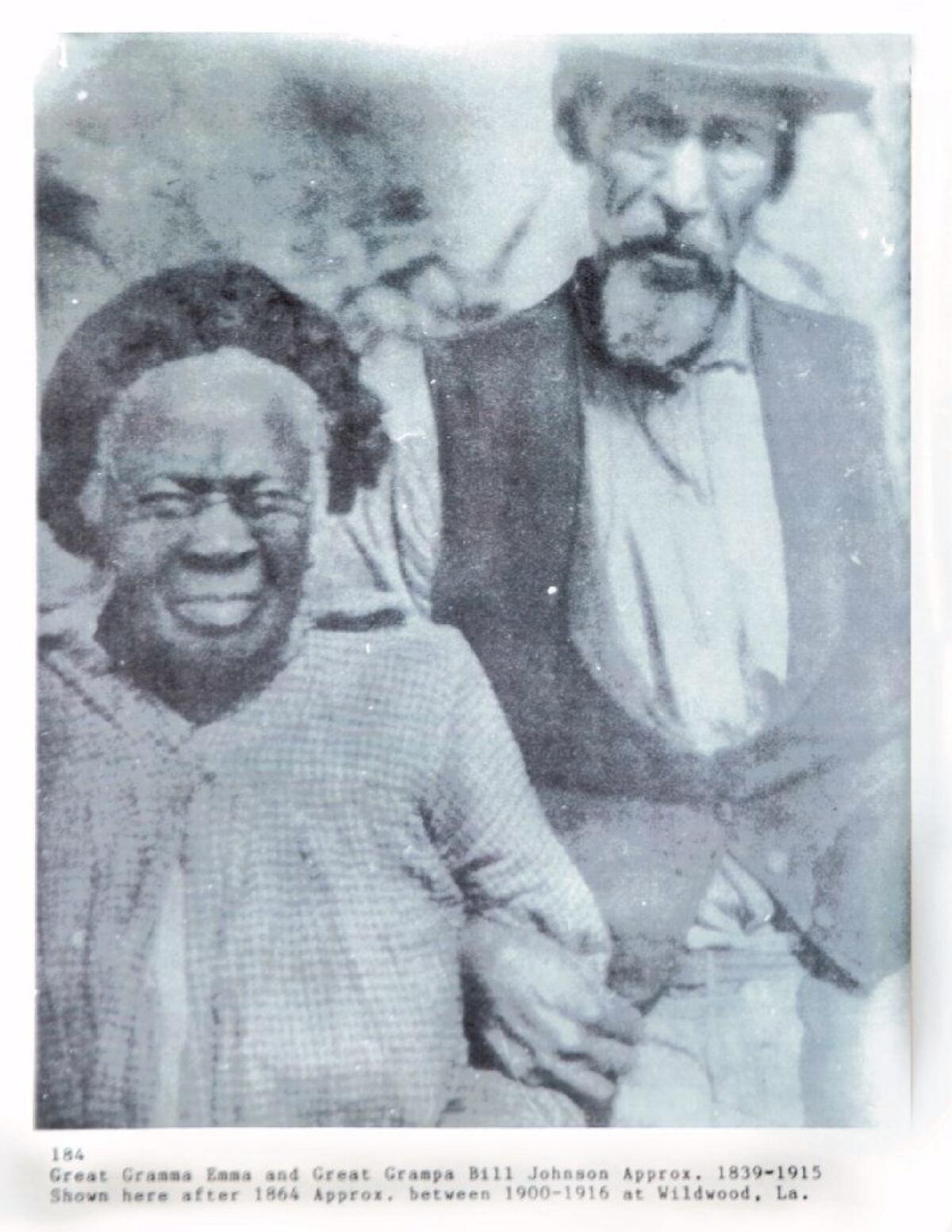

Three photos from the journal particularly inspired her. The first was a shot of her great-great grandparents Emma and Bill Johnson, taken between 1900 and 1916 in Wildwood, La.

“They would refer to her as ‘the Guinea Woman,’ even though she wasn't necessarily from Guinea, but because she spoke her native language,” Rees said. “They called him ‘the Arab man’ and the mythology is that he was the son of a slave trader and his father told him not to go up near the boat, but he did and that’s how he ended up enslaved.”

If I can go three grandmothers back and find a slave, that means somebody else can go three grandmothers back and find a slave owner.

— Dee Rees, writer-director

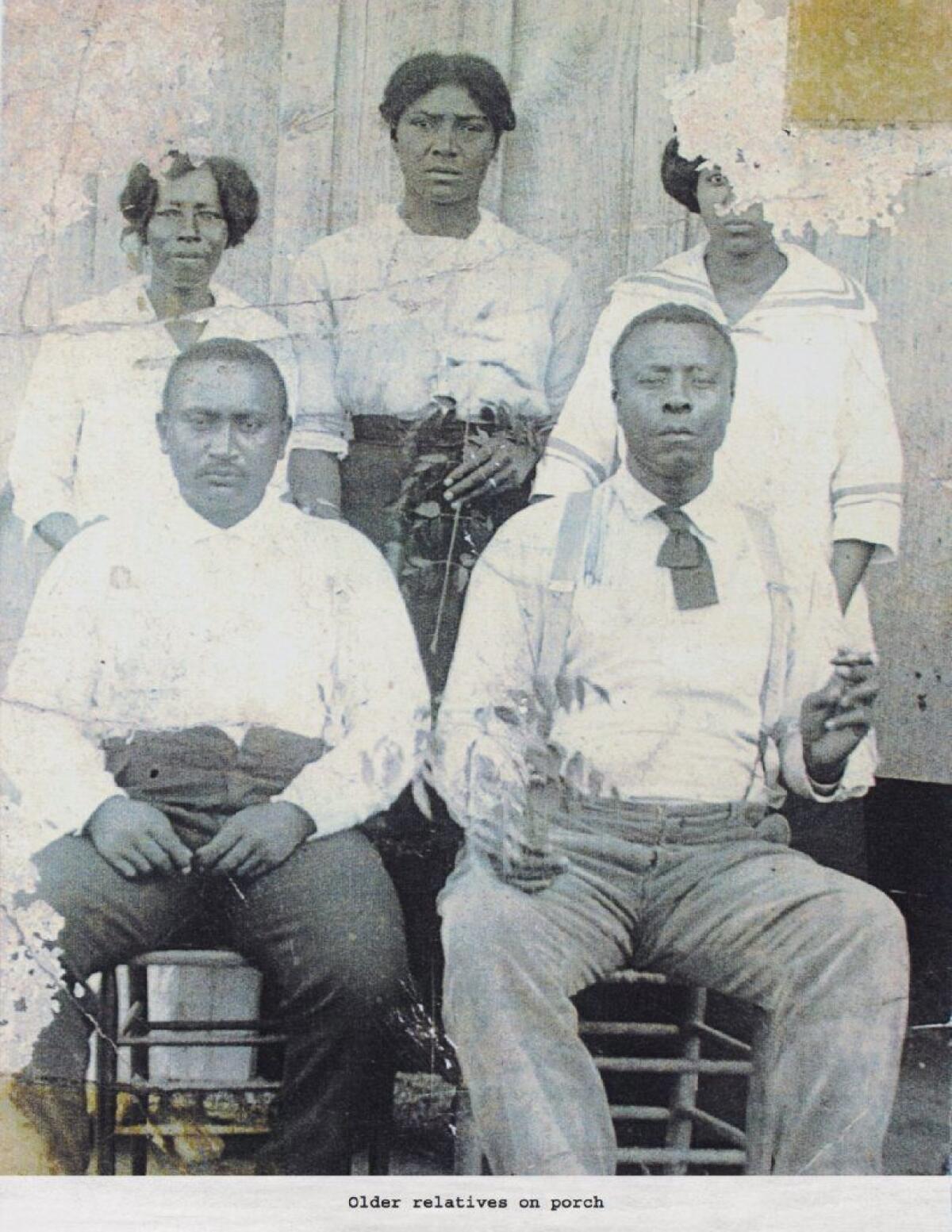

The second photo is a family portrait of some of her relatives who were slaves. They’re dressed in their Sunday best, holding flowers and cigars.

“Apparently it was a picture of all the slaves on the plantation, but they stood in family groups and cut [the photo] up and everybody got their piece of it.”

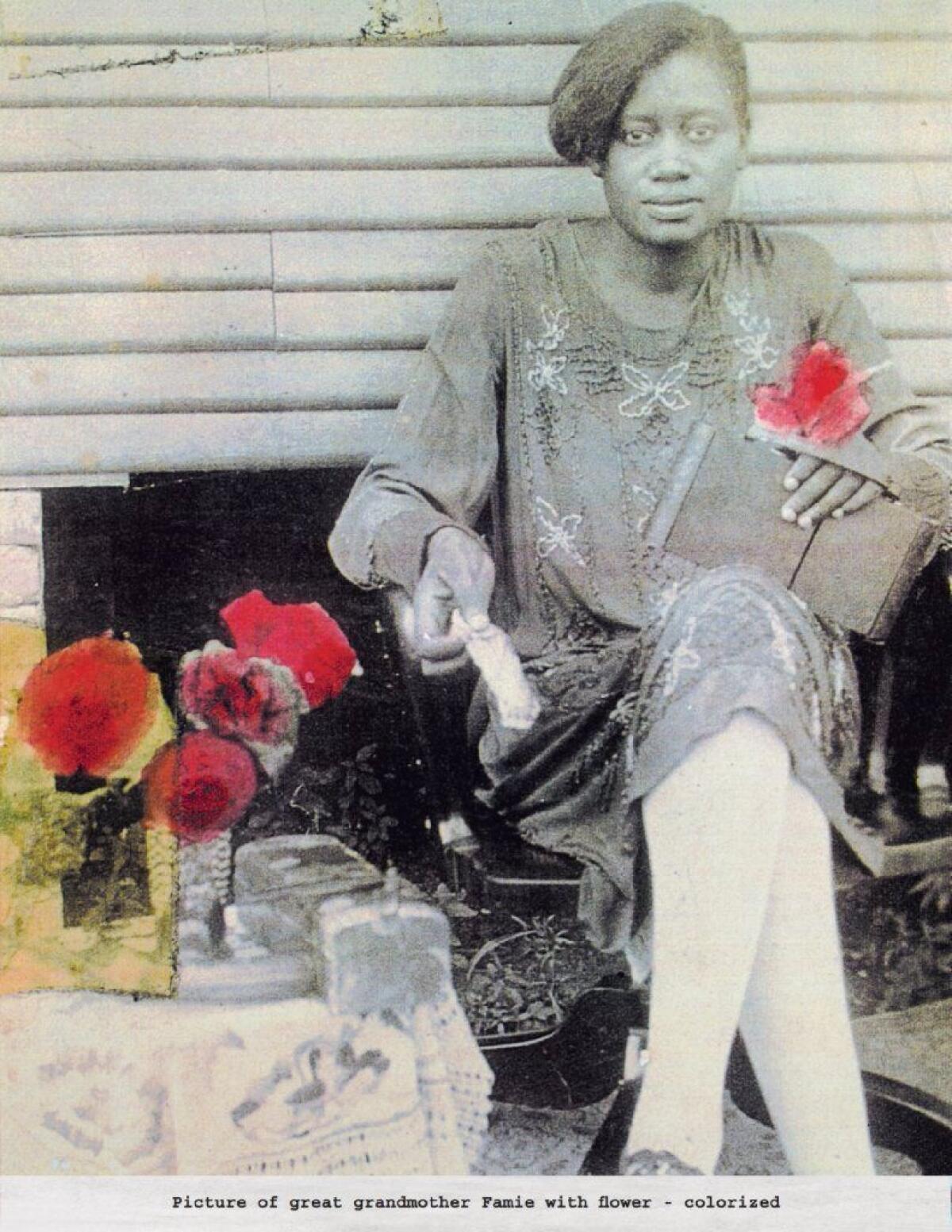

The third image is of Rees’ great grandmother Famie, Smith’s mother. She holds a handkerchief and a flower, her hair coiffed and swept to the right side of her face.

“My grandmother told me stories of how she would comb her mother’s hair and there was a sink in her skull, where it was caved in, where she was bashed in the head,” Rees said. “And she told me how she and her brother, Clarence, used to ride on the back of her mother’s cotton sack. That’s why there’s a scene like that in the movie.”

These photos told Rees that the time period “looked differently than it typically gets presented,” she said.

“[Black] people kept homes and had ideas about ownership and advancement that they didn't share necessarily with their white counterparts [because] there was this idea that you can have too much ambition.”

That’s why in the film, for example, the Jackson daughter (Kennedy Derosin) wants to be a stenographer, as opposed to a singer as depicted in the book. (Smith wanted to be a stenographer when she was younger.)

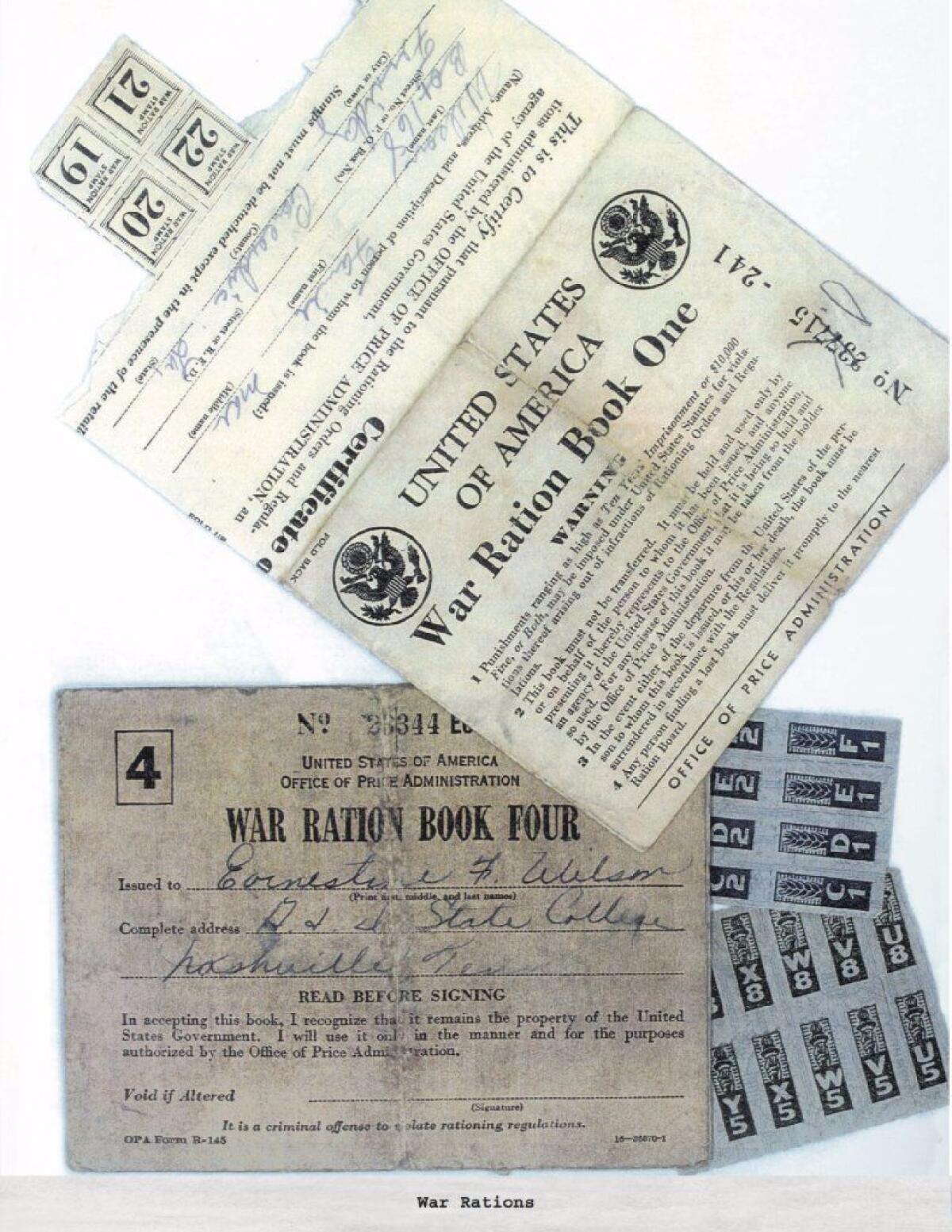

Other parts of the journal were also used. A war ration book, for example, inspired a scene in which sugar is purchased as a luxury for the Jacksons. Written text from the journal, about country life and communal love, informed the importance of a number of key scenes Rees created that were not in the book that better set the scene and build an audience's penchant to care about the characters, she said.

But perhaps the greatest inspiration however came from the life of Smith herself who died in 2010 but, as noted in Rees’ 2008 documentary “Eventual Salvation,” expatriated in Monrovia, Liberia in 1954.

“My grandmother said, ‘I will never be a citizen in this country,’” Rees said. “And what she meant by that was that this country will never see her as a first class American citizen. She’d always be a problem, or a reminder.”

A similar concept is present in “Mudbound” where Mitchell’s Ronsel returns from war, where he and all of the black soldiers were treated as Americans, to a place where he must enter and exit stores through rear entrances.

“I wanted to explore how these black soldiers are received [abroad] first as Americans then as black men,” she said. “But here, they’re received only as black men, and I don’t know if they're ever seen as American.”

And the plot-point couldn’t be more relevant for audiences in 2017, she said.

“It’s what Claudia Rankine is writing about: Are you and I first seen as Americans? Maybe not. Maybe black and then lesbian — if they can read that — and then, maybe American.”

“And it sounds hokey but there is this interconnectedness of our narratives. It’s not this separate your history and my history,” she said about what she hopes audiences take away from the picture. “If I can go three grandmothers back and find a slave, that means somebody else can go three grandmothers back and find a slave owner. And you have to own that, not just for the shame of it but to understand what you inherited.”

“We can't have this ‘That wasn’t me. I didn’t do it [thing…]’ Even if that is not your narrative, and your grandfather came over from Italy with $2 in his pocket, OK. If that’s a noble narrative, why can’t someone come over with $2 in their pocket now? Use that narrative and be about immigrant rights. There’s a way to use that to make the world better because guilt is a useless feeling.

“And for black people, shame is a useless feeling. And the shame is not ours.”

This story is part of The Times' Holiday movie preview. See our complete coverage here.

Get your life! Follow me on Twitter (@TrevellAnderson) or email me: trevell.anderson@latimes.com.

ALSO:

Dee Rees and the cast of 'Mudbound' create a vibrant, intertwined history

Mudbound' director Dee Rees shoots for the stars and gets her dream cast

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.