Biopics find new life at the Oscars and beyond

Looking across the Oscar nominations you’ll see a landscape populated by pictures about real people. Look beyond the Oscars and you’ll see even more. The last 12 months has produced an abundance of biographies. It’s as if film’s current artistic collective decided to figure out what subject matter works for contemporary audiences — whether it spans the years or zeros in on a particular critical event.

The result is essentially a master class in how to use a movie to tell the story of a life. That not all the films are worthy of an A is an indication of how prickly the process can be. In a sense, biographical fare starts with at least one strike against it. The shorthand used to describe the genre — “biopic” — comes as an indictment. The label has become, or perhaps it always was, a pejorative term, dismissive of the idea itself, hinting at a kind of overly earnest, fawning film that clings more to the mythology of a life than the reality of it and is probably dull to boot.

In broad strokes, I’m referring to something larger. Films that tackle a real life, to be sure, but filled with complexities to be teased out, controversies to be explored. Ones shaped by a vast array of external forces — sickness, war, discrimination, poverty, wealth, religion. Driven by a distinct internal alchemy — brilliance, talent, ego, ethics, desire, expectations, desperation. Some end in triumph, others tragedy.

It’s no surprise that filmmakers find themselves fascinated or that actors are so eager to play them. Their stories are especially tempting for those in the movie trade, coming as they do fully realized — the charismatic appeal, dramatic arcs, unimaginable plot twists are built in. It’s humankind at its best and its worst, though Hollywood favors the heroes.

Translating all that to the big screen is where the difficulty lies. Even those who succeed also stumble. Consider Oliver Stone, one of our more prolific biographers. The director’s Oscar winners “Born on the Fourth of July” in 1989 and “JFK” in 1991 and in 2008 the underappreciated “W.” stand among his better films, his go at the famed military strategist of Macedonia, “Alexander,” in 2004 an embarrassment.

Clint Eastwood, in the Oscars running and also taking heat for turning a killing machine into a hero in “American Sniper,” fumbled 2011’s “J. Edgar,” starring a bloated Leonardo DiCaprio and a flat script. And Bennett Miller, also in the current directors’ race with “Foxcatcher,” may find it tough to top the memory of his taut, well-told “Capote” (2005).

All of the basics required of any great film must be there — stirring dialogue, impassioned performances, emotional depth, exceptional craft. Every year one or two biographical tales surface as standouts, so artfully executed the films go toe to toe with the industry’s imaginative best. Like Martin Scorsese’s black-and-white and bruising “Raging Bull,” starring Robert De Niro as boxer Jake LaMotta. Todd Hayes’ inventive “I’m Not There,” using multiple actors, men and women, to underscore the enigma of Bob Dylan. Gus Van Sant’s straightforward but emotionally evocative look at slain gay political activist Harvey Milk in “Milk.”

That very eclecticism of storytelling and style has characterized some of the recent best picture winners. Last year’s “12 Years a Slave,” based on freeman Solomon Northup’s antebellum memoir of his kidnapping and years spent on Southern plantations, used a life to make the abstraction of slavery concrete. “Argo,” in 2012, was rooted in one CIA agent’s brash plan to rescue American hostages in Iran and played like a spy thriller. A year earlier, “The King’s Speech” took a single slice of King George VI’s reign — his linguistic battles and a particular speech to his country during some of WWII’s darkest times — and left the rest for others.

There are inherent challenges whether the central subject is well known or not. The unknown require a complete introduction. The known, as the makers of “Mandela” discovered last year, sometimes eclipse the film. The passage of time helps, perspectives deepen. Spike Lee’s “Malcolm X,” starring Denzel Washington, benefited from the director’s measured look back at the controversies as well as the man.

This year’s bumper crop — “American Sniper,” “Foxcatcher,” “The Imitation Game,” “Selma,” “The Theory of Everything,” “Wild,” “Rosewater,” “Mr. Turner,” “Unbroken,” “Big Eyes,” “Get on Up,” “Jimi: All Is by My Side” and “Tracks” — have little in common other than their biographical base.

Not all made the Oscar cut, but among those that did, they snagged 35 nominations across the major categories, including best picture, four of eight; director, two of five; actor, four of five; actress, two of five.

Sometimes the storytelling does justice to the legacy as in, say, “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Gandhi,” “Out of Africa,” “Schindler’s List,” “A Beautiful Mind,” each earning a best picture Oscar for its efforts.

There are, however, far more failures: “Amelia,” Mira Nair’s nosediving account of pilot Amelia Earhart starring Hilary Swank; “Beyond the Sea,” with Kevin Spacey directing and starring in this off-key account of crooner Bobby Darin; the laughable look at Apple genius Steve Jobs in 2013’s “Jobs,” starring Ashton Kutcher, to name a few.

The challenge is the translation. Difficult to decide what to pare, how much license to take. It essentially boils down a question of how true to the truth must a filmmaker be and how much of the truth must be told?

You can see that struggle being played out now: Ava DuVernay’s “Selma” is in the hot seat with historians picking apart its depiction of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s role in Martin Luther King Jr.’s historic voting rights march. In contrast, Angelina Jolie’s “Unbroken” is bearing criticism for being so by-the-book in recounting WWII-vet Louis Zamperini’s remarkable survival story in such detail as to be unsurprising.

The actors needn’t look like the characters, though for well-known public figures at least a passing resemblance doesn’t hurt: George C. Scott in “Patton,” Ben Kingsley in “Gandhi,” Eddie Redmayne as theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking in “The Theory of Everything.”

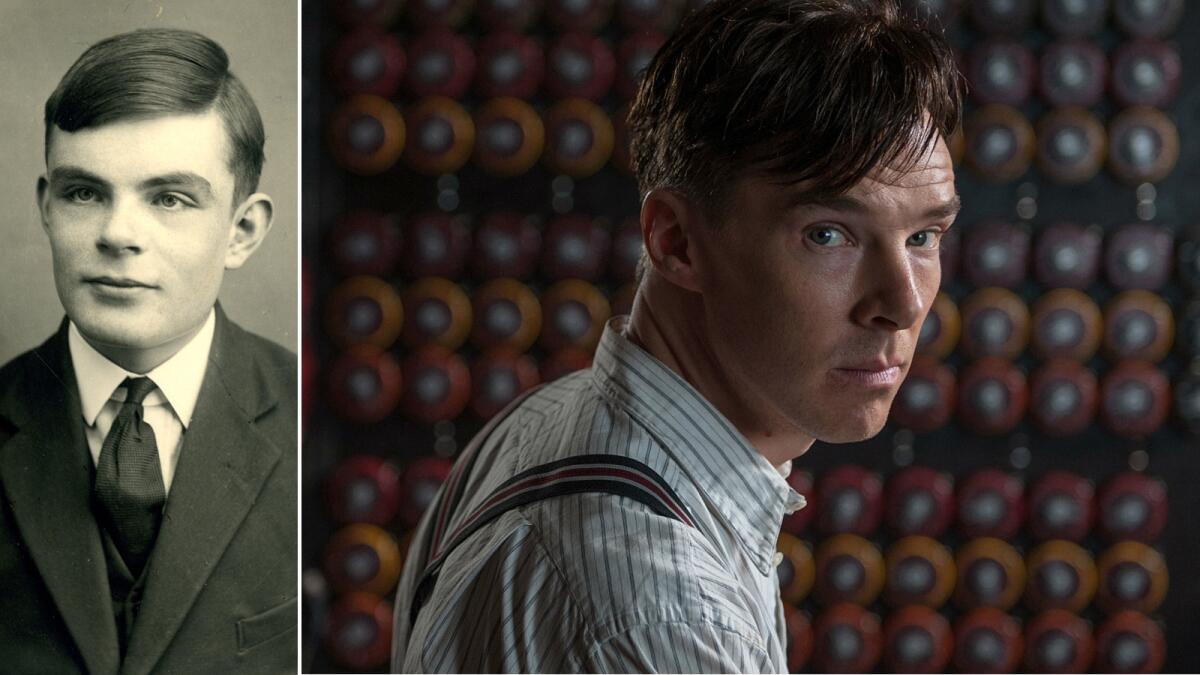

The stars must, however, embody the essential spirit of the person — “Get on Up’s” Chadwick Boseman sweat-drenched frenetic theatrics echoing James Brown in action, Benedict Cumberbatch putting a fine point on Alan Turing’s agitated genius and his oppressed sexual orientation in “The Imitation Game,” Steve Carell eerily channeling the loathsomeness of murderous millionaire John du Pont in “Foxcatcher.”

Whatever your view of the historical accuracy debate hounding “Selma,” the film is made more incisive and inspiring by focusing on a single, seminal event in King’s fight against discrimination. “Capote” was made more memorable by its emphasis on the back-story of one of Truman Capote’s finest books, “In Cold Blood.”

The approach doesn’t guarantee success, of course. Though Meryl Streep’s portrayal of Margaret Thatcher in “The Iron Lady” a few years ago earned her an Oscar, the film itself failed Thatcher and moviegoers. By concentrating on her late-in-life confusion, the central core of the former British prime minister’s groundbreaking accomplishments was lost.

A balance between ideas, emotions and the actual life form another piece of the equation. With “Gandhi,” the message as much as the man carried the film. In “The Theory of Everything,” scientific genius shares the stage with romance. In “The Imitation Game,” exposing the draconian laws that turned a war hero into a prosecuted outcast shared center stage with Turing.

When filmmakers get it right, it makes for exceptional watching. For truth is not only stranger than fiction, it’s often more compelling.

Twitter: @BetsySharkey

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.