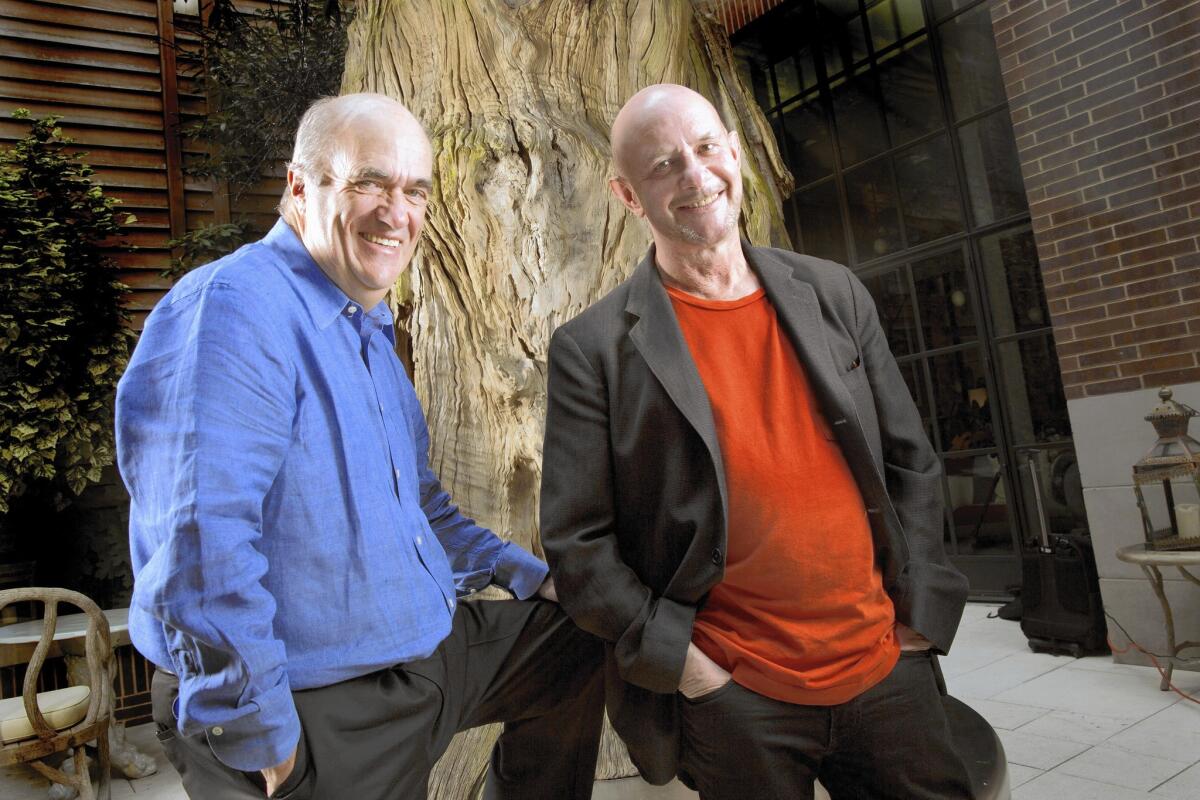

Nick Hornby, Colm Tóibín describe ‘Brooklyn’ as a ‘weepie’ that ‘punches you in the stomach’

A young person setting off in search of opportunity and romance would seem like one of the more popular cinematic destinations.

So popular that, as Yogi Berra might have said, no one goes there anymore.

“Weirdly, it’s an act of nerve now to write a movie that makes you feel,” British novelist and screenwriter Nick Hornby said at a downtown restaurant here recently. “And I don’t understand why that is. Why are we scared of a ‘50s weepie? Why are we scared of a movie that pulls you in and punches you in the stomach?”

SIGN UP for the free Indie Focus movies newsletter >>

Hornby confronted those fears with his latest screenwriting effort, “Brooklyn,” based on Irish writer Colm Tóibín’s lauded 2009 novel.

Directed by John Crowley (“Boy A”), “Brooklyn” arrives in theaters Wednesday as the rare award-season bird, a delicate emotional story that stands in contrast to the fireworks of fact-based dramas and a larger culture, even among big Hollywood movies, of dark anti-heroes.

The film tells of Eilis, a young woman in 1950s Ireland who makes the boat trip from her small town to the titular borough, leaving behind a single mother and a beloved older sister. On arriving in the New World, Eilis (Saoirse Ronan, in a tour-de-force performance) is greeted by some of the native accouterments: a job as a department-store clerk, an all-female boarding house and, particularly, the affections of a young Italian American man (Emory Cohen). Eventually, a tragedy forces Eilis to confront a kind of excruciating ur-choice, between the comforts of home and the thrill of the unknown.

By having a woman in a postwar melting pot face eternal questions, the story achieves a kind of narrative holy grail; “Brooklyn” is a tale of both telling specificity and stout timelessness.

“I wanted to say a lot about difference,” Tóibín said, sitting across from Hornby as the two sipped hot beverages the day after their movie’s New York Film Festival premiere. “How you have to make friends with people you can’t read. How somebody is in a place where she can’t acclimatize fully, and then goes home, but when she goes home finds it isn’t really home anymore either.”

Watch Q&As with the ‘Brooklyn’ cast and crew

Video: 'Brooklyn': John Crowley and Saoirse Ronan examine the film's subtle dramatic moments

Video: 'Brooklyn': How the film never tips it's hand

Video: 'Brooklyn': Ireland-born Saoirse Ronan on being Irish for the first time on-screen

Video: 'Brooklyn': John Crowley and Saoirse Ronan explain the film's final boat scene

Video: 'Brooklyn': What it took to capture the Irish spirit

Tóibín based the story of a young woman separated from her family in part on his own experiences growing up in the small Irish town of Enniscorthy, where the novel is also partially set. As a child, all the émigrés he would hear about were young people traveling solo. In contrast to other immigrant groups, their parents would seldom accompany them — “the secret history of Ireland,” he calls it.

The author also drew from another part of his past.

“I had been in Texas teaching a number of years ago and it was all very nice and the job was nice, but I found it difficult. I just wanted to be home” in Ireland, he said. “And then when I got home, I found that it didn’t feel right anymore either.”

Complex feelings of emotional displacement can be hard to capture in 110 minutes of screen time. It’s one reason why many filmmakers don’t even try, or conceal their intentions behind other facades.

...As a screenwriter you realize, ‘Well, it doesn’t work if you include everyone’s favorite scenes.’

— British novelist and screenwriter Nick Hornby

Hornby, however, said there was little sense going against the grain of the novel. “It was very conscious on my part not to write anything that was veiled in irony or distance,” he said. “If this movie was going to work, it would have to make you feel.”

Fans of the book will find some of its key parts compressed — Eilis’ early days in Ireland, for instance — and also watch a film that brings its main character’s romantic journey, on which she must choose between a man in New York and a man in Ireland, to a more rounded conclusion.

Those adjustments were necessary, Hornby said.

“One of my experiences being on the other side is when you’re adapting a novel, there are always scenes taken out of the book, and no matter which scenes they are it’s always someone’s favorite,” he noted. “And then as a screenwriter you realize, ‘Well, it doesn’t work if you include everyone’s favorite scenes.’”

Tóibín added, “I think Michael Ondaatje said it well — ‘The screenplay tries to find the short story within the novel, and then goes for that short story.’”

The finished film is a manifestation of its two writers’ aesthetics: It blends the surprising melancholy of a Hornby work with the thematic investigations of a Tóibín one.

Tóibín, who has a kind of endearingly wide-eyed quality about the film world, is a veteran novelist who, in books such as “The Heather Blazing” and “The Blackwater Lightship,” has explored issues of identity and alienation, often with an Irish spin. He said he has long been fascinated by subtle differences in temperament between Irish and Americans.

“There’s a unique American kind of charm, I find. A guy in Ireland is smiling all the time, but there’s something of ‘get him drunk and you’ll see who he really is.’ In America, you find those smiles are real,” he said. (The writer, 60, lives in Dublin and New York but has recently begun spending more time in Los Angeles because of a boyfriend there.)

As a screenwriter, meanwhile, Hornby has been making a shift from the manchild characters that defined his early career in novels such as “High Fidelity” and “About a Boy.” His most recent two scripts were “Wild” and “An Education” — like “Brooklyn,” stories of tough young women undergoing a crucible.

“I only want to write books and movies about women,” said Hornby, 58. That’s true even though he’s often cited as the chronicler of a masculine id, a kind of poster-child for, and savior of, a male readership feared growing extinct.

“I think it comes to a point where you start feeling a little chippy,” he said, giving a small laugh. “‘I only write for guys who don’t read.’ There becomes an element of ‘maybe I should do something else.’”

Immigration stories have not been uncommon in the independent-film world, though these days they tend to involve the Mexican-U.S. border more than European transplants. Earlier Irish-themed pieces, such as Jim Sheridan’s 2003 film “In America,” have been critical successes but a more mixed bag commercially.

Whether “Brooklyn” will find an audience will depend in part on an older demographic, which is most likely to respond to its throwback vibe and setting. But younger people may well appreciate the film too, Ronan said.

The 21-year-old actress, who first came to light with her Oscar-nominated turn in 2007’s “Atonement” and embodies a resonant soulfulness here, told the New York Film Festival audience that the story spoke to her own experience. “I was in that place myself,” Ronan said, describing an adult move from Ireland, where she’d spent much of her life, to England. “And everything in your early 20s is very new and extreme and raw, so I could totally empathize.”

Hornby said he had just that desire: to create a story divorced from its era and enrobe it in more timeless emotion.

“It’s set in a period, but it’s not about the period,” he said. “I mean, being young and confused is something we all go through at least once.”

ALSO:

‘Our Brand Is Crisis:’ Is cable news taking a toll on the political drama?

Evander Holyfield looks to come to terms with Mike Tyson in new documentary

‘Point Break’ remake looks to make a cult classic new, and serious

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.