‘On Chesil Beach’ marks a cinematic return for Ian McEwan 10 years after ‘Atonement’

Hollywood being what it is, and authors being who they are, film productions don’t tend to involve many novelists.

They’re rarely granted the chance to adapt their own screenplays; they make it to movie sets even less frequently.

So it was strange for Ian McEwan to find himself on a London soundstage in 2016 as the screenplay he wrote for his wistful 2007 romantic novel “On Chesil Beach” began shooting.

And it was even stranger when the adaptation of his screenplay for his 2014 novel “The Children Act,” a story of a middle-aged judge thrown for a loop, began pre-production on the same day right next door.

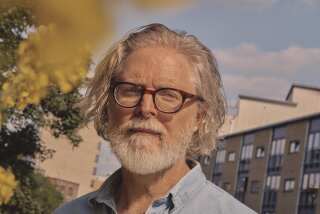

“I’m not the person who wants to small-talk with actors between set-ups or go over to the director to murmur ‘that’s not how I envision a scene;’ I don’t like being the bad conscience of the set,” the unpredictable British author, 69, said over lunch last September at the Toronto International Film Festival, where both movies were premiering.

“But it was still,” he says, “kind of dreamy.”

The moment was especially fantastical for McEwan because of how long it has been — he hadn’t had a screenplay made into a movie since the early days of Prime Minister John Major (“The Innocent,” 1993).

And it had been a decade — almost to the day — when the movie based on his novel “Atonement” had premiered at TIFF.

“It’s a bit of ‘Groundhog Day,’ isn’t it,” said the Booker Prize winner of “Chesil” — as with “Atonement,” also a piece of period romantic melancholia starring Saoirse Ronan.

Except “I Got You Babe” was unlikely to be playing on a clock-radio loop. Things in fact were generally very different this time around. Most significantly, the film world had changed, moving further away from the kind of adaptation of sensitive literary work that made “Atonement” an Oscar-season favorite in 2007.

Exhibit A: It took “On Chesil Beach” several weeks to land a U.S. distributor after Toronto ended. It wound up with Bleecker Street Pictures, which opened the film in limited release on May 18.

“The Children Act” was acquired faster — by A24 and DirecTV during the festival — but will be released later. The film, featuring an acclaimed turn from Emma Thompson, is expected to arrive in theaters later this year.

For the past two decades, McEwan has been one of the English-speaking world’s most acclaimed novelists, turning out fiction as reliable in its quality as it is diverse in voice and subject matter. Beginning with “Enduring Love,” his two-hander about obsession and a deadly accident, in 1997, McEwan has continually published mononymic work of impeccable genius: “Atonement,” Amsterdam,” “Saturday.”

Most recently, it was 2016’s ”Nutshell,” a novella that prequels “Hamlet” from the perspective of a young hero — so young he’s a fetus.

But “Atonement” notwithstanding, his writing has proved stubbornly inimical to the movies, either getting pale adaptations or no adaptations at all.

Partly, it’s the author himself. The richness of McEwan’s prose, which might be described as filled with smooth complexities, and the deeply interior lives of his characters make cinema an unnatural fit.

Those difficulties have not been lost on the author, who says it never fails to astound how divergent the act of creating fiction for each medium can be, particularly when it comes to removing thoughts and description for film.

“It’s the problem for all adapters,” he said. “As a novelist, you’re in your best clothes. And suddenly you have to strip down to your underwear.”

So how exactly did two movies happen in so short a span?

Some of it was just the vagaries of development — “Chesil” could have gone into production a while back, when Sam Mendes was developing it. But the director left to work on the James Bond franchise, and it delayed a greenlight until “Chesil” abutted the production of “Children.”

Some of it was a new push on McEwan’s part — he had decided not to adapt “Atonement” so he could work instead on a new novel, but “Chesil” was too important for him, he says, to leave to others.

But much of it was just luck. It’s not like he hadn’t wanted to have movies made earlier; he collaborated with the likes of Paul Schrader on projects that didn’t get off the ground. He notes a steady reminder of Hollywood’s presence in his life with the very small royalty checks that arrive regularly for a relatively minor movie adaptation, “like a struggling uncle in Los Angeles.” Those who assume the stereotype of the British author purposefully removed from Hollywood — “Brooklyn’s” Colm Toibin comes to mind — will find a very different type in McEwan.

Still, actually getting movies made required plenty of negotiation with the material, a fine parsing of the differences between film and novels.

With “Chesil,” directed by Dominic Cooke, it meant conjuring lost love with images. The flashback-heavy film centers on a couple (Ronan and Billy Howle) from rather different class backgrounds honeymooning in a romantic spot in the 1960s, charting what brought them together and what eventually split them apart.

McEwan based “Chesil” in part on a story from his own young romantic life — the woman, Florence, from a privileged background, he the working-class kid who fell in love with her. He says the film still has the power to push his buttons; “even though I’ve watched 19 versions of it, bits make me cry.”

REVIEW: Saoirse Ronan and Ian McEwan reunite for tragic romance ‘On Chesil Beach’ »

The end of “Chesil” was particularly tricky. In the book, it spans several decades, with an assist from some deft narration. McEwan had to come up with a way to convey this without telegraphing it. (A touching record-store coincidence helped do the trick.)

“There’s an essay [Joseph] Conrad wrote that said his duty as a novelist is to make you see…to let the reader invent an inner cinema,” McEwan said. “And that’s become a constant point of reference in my novels — the key to any strong emotional scene are its visual elements. I hope the director sees that,” he added. “Because I don’t want to give direction in a screenplay.”

McEwan said that, for all the hard choices, he has sought to find enjoyment in the process of adaptation — “the pleasure of adapting your own work is you get go back into it and find new scenes, almost like a meditation” — even as he remains skeptical of the publicity-circuit required to promote it. (“It seems a long way from the pleasures of moviemaking.”)

In the meantime, he’s trying to make headway on a new undisclosed novel, even as the world around him seems more dramatic than anything he can come up with.

Would he, indeed, ever write about Donald Trump?

“It’s very difficult, partly because it’s moving so fast and partly because the unbelievable outstrips fiction,” he said. “It’s great for longform journalists, but novelists need to sit with stuff for a while. And this won’t sit still.”

If he did try it, it would be in a certain way. “Novels work best when they’re so personal. You’ve got to find the human. The novel about President Trump is not about someone who looks like President Trump,” he added, in a comment that seems to explain much of his fictive philosophy. “It’s the man or woman who lives in the shadows who has their life penetrated by him.”

And of course, there’s always a return to movies. Fans of “Amsterdam,” the story of a complicated relationship between a composer and a journalist that won him the Booker, will wonder if perhaps one based on that book could be in the offing.

Is there at least some movement on it?

“The option,” he said, efforting a smile, “is available.”

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.