Indie Focus: Come away with ‘Midsommar’

Hello! I’m Mark Olsen. Welcome to another edition of your regular field guide to a world of Only Good Movies.

This week, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced the invitation of 842 industry professionals to be new members. Among the invitees were “The Nightingale” filmmaker Jennifer Kent, “The Love Witch” filmmaker Anna Biller, “Madeline’s Madeline” filmmaker Josephine Decker, “Free Solo” co-director Jimmy Chin and “Blockers” writer-director Kay Cannon, all of whom spoke to The Times for our story.

On July 8, people in Los Angeles can also enjoy the academy’s 35 mm screening of 1975’s coming-of-age dramedy “Cooley High.” The event will be hosted by Robert Townsend and among the scheduled guests will be director Michael Schultz, Lawrence-Hilton Jacobs, Larry Karaszewski and Garrett Morris.

Times critics Kenneth Turan and Justin Chang surveyed their favorite films of the year so far, including “Peterloo,” “Her Smell,” “Maiden,” “The Souvenir,” “Birds of Passage,” “High Life” and more.

For the LA Times entertainment podcast “The Reel,” this week I spoke to Blake Howard about the conclusion of his podcast project “One Heat Minute.” With an obsessive enthusiasm, for some two years, Howard has been going through the 1995 crime drama “Heat” one minute at a time. For the show’s finale, he was able to speak to the movie’s writer-director Michael Mann.

We have some very exciting screening events scheduled for July. For info and updates on future events, go to events.latimes.com.

‘Midsommar’

As the follow-up to his horror hit “Hereditary,” writer-director Ari Aster is back with the slow-boiling freak-out of “Midsommar.” When a young woman, Dani (Florence Pugh), suffers an intense family tragedy, she receives little solace from her increasingly distant boyfriend, Christian (Jack Reynor). When she tags along with him and a group of anthropology grad students to a small Swedish village, they are both drawn into a world of rituals and customs far beyond their control.

In his review for The Times, Justin Chang wrote, “Amid scenes of revelry, ritual sacrifice and very bizarre sex, what you remember most is the extraordinary commingling of terror and exultation in Dani’s eyes as she beholds the fate that awaits her and her companions. Aster’s control is startling: With diabolical suggestiveness he keeps widening the chasm between Dani and Christian, placing visual and emotional space between two people whose souls have long since drifted apart.”

I spoke to Aster, Reynor, costume designer Andrea Flesch and production designer Henrik Svensson about the level of attention and detail that went into creating the film. As Aster put it, “For me, the film is incidentally a folk horror film. If anything, this is my attempt at making a big operatic breakup movie that feels the way a breakup feels.”

For the New York Times, Manohla Dargis wrote, “Horror depends on the spectacle of human frailties, on the good and foolish choices that bridge the distance between the viewer and the screen (or blow it to smithereens). But when characters are as stupid as the visitors in ‘Midsommar,’ it only encourages your sadism, which is presumably the point.”

For The Ringer, Lindsay Zoladz wrote, “ ‘Midsommar’ would not be the first time a filmmaker tried, with his sophomore film, to do a bit too much. It’s more subtle than the crushed skulls and flayed bodies, but what Aster has proved with this movie is how good he is with the horror of the everyday. The scariest parts of this movie are the most banal: Dani’s lack of an emotional support system, Christian’s culturally sanctioned entitlement, and the mutual terrors of codependency.”

For Vanity Fair, Richard Lawson wrote that the film, “arrives at something rather staggering, an image of a shattered person who finds sudden release — catharsis even — in a radical realignment of her thoughts about existence and worth and, finally, loyalty. I won’t spoil anything further, but ‘Midsommar’ might just be the year’s definitive take on the war of heterosexual coupling, on our constant wrestle with mortality, on the creeping fear that the devices and understandings of modern American life are perhaps inadequate tools to explain, and buttress us against, the mysteries of being. Happy Fourth of July, I guess. And a deeply unhappy Midsommar.”

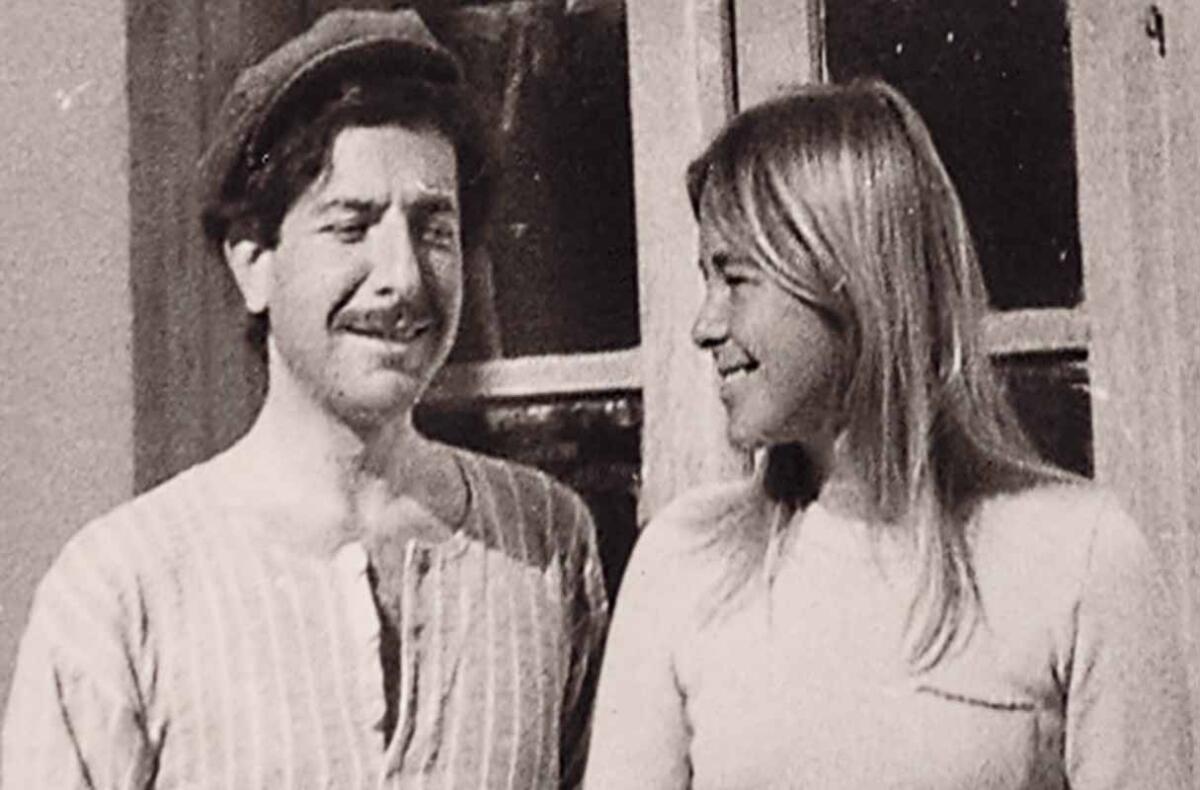

‘Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love’

Documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield is notorious for inserting himself into the story of his films. With “Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love,” the story of Marianne Ihlen and Leonard Cohen and their intense romantic bond, Broomfield has reason to make himself part of the film. As a young man he too had an affair with Inhlen, one that was a vital inspiration to the beginnings of his career.

In a review for The Times, Kenneth Turan wrote, “Love stories are like Tolstoy’s unhappy families: No two of them are alike. But even given that, the relationship chronicled in ‘Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love’ has a quality very much its own.”

For the Chicago Tribune, Katie Walsh compared the movie to Broomfield’s other work when she wrote, “There is no mystery to probe, no conspiracy theory to prove, so Broomfield the bumbling provocateur is not necessary. Instead, he positions himself as Marianne's occasional respite during her tumultuous, nearly decadelong relationship with Cohen, whom she met on Hydra as well, in the early '60s… If Broomfield has anything to argue, it's the great influence of Marianne in the life of the iconic singer, as lover, inspiration, financial support and muse.”

For Rolling Stone, David Fear wrote, “What makes this film unmissable, however, is the fact that we get Marianne’s story more or less in full as well. It’s a fleshing out of someone who was more than just a muse, more than just an object of affection for a notorious ladies’ man, a famous singer and an infamous bastard... There’s a reason her name comes first in the title. Marianne is no longer just “Leonard’s muse.” She’s a woman who’s lived and loved and lost completely apart from the songs.”

‘The Chambermaid’

The debut feature for Mexican director and writer Lila Avilés, “The Chambermaid” is a delicate observation of class and everyday struggle. In the film, a woman (Gabriela Cartol) works as a housekeeper in a luxury hotel in Mexico City and finds herself increasingly drawn toward unraveling the mysteries of the lives of those she services, even as she tries to maintain her connections to the world outside.

In a review for The Times, Robert Abele said, “‘The Chambermaid’ is empathy cinema but hardly miserablist in its shape… In the end, “The Chambermaid” is the kind of service industry character study that in these compassion-challenged times performs its own dutiful service.”

For rogerebert.com, Monica Castillo compared the film to “Roma” for its depiction of domestic workers when she wrote, “Avilés is more interested in the minutiae of her character’s life than making larger social commentary, her lens instead focused on Eve’s dull tasks, the family she calls often, and her ambition to move up in the hotel’s hierarchy. With her film, Avilés unlocks a world full of hope and disappointment, a workday that may bring peril or boredom. It may feel less epic in scale, but ‘The Chambermaid’ is just as emotionally potent and perhaps even more successful at questioning the power dynamics of a workplace that has lost its sense of compassion.”

Email me if you have questions, comments or suggestions, and follow me on Twitter: @IndieFocus.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.