Review: Radical Islamists tried to take away Mali’s music, but the musicians of ‘Mali Blues’ play on

Music documentaries are thick on the land, and political ones are numerous as well, but “Mali Blues” is different in that it artfully combines hypnotic music with definite societal concerns.

If you are a fan of world music, you’re aware of the terrific sounds coming out of the West African nation whose musical citizens include the great Ali Farka Touré and the Tuareg band Tinariwen.

And if you’re a movie person, you remember 2014’s “Timbuktu,” the Oscar-nominated film that dramatized what happened when radical Islamists took over that storied city in Mali.

As “Mali Blues” documents, those fanatics banned playing and even listening to music, causing musicians to flee for their lives to the country’s relatively more liberal south and sending shock waves through the entire Malian music community.

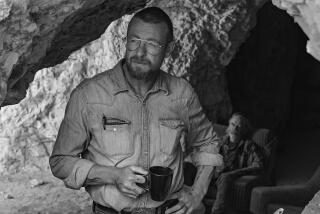

Directed by veteran German documentarian Lutz Gregor, “Mali Blues” shows how the musicians reacted and provides generous amounts of their music as part of the mix.

One reason for the shock waves is the centrality of music to Mailian culture.

“I can’t imagine a life without music,” says Fatoumata Diawara. “It would be like the Earth stopped turning.”

Diawara, a world music star, is the first musician “Mali Blues” introduces us to. Raised in Mali, she is now returning to Bamako, the capital city. Her life story, only gradually revealed, is the film’s through line.

Featured next is Ahmed Ag Kaedi, leader of the Tuareg band Amanar, a guitar virtuoso in a white turban who fled to Bamako from his northern city of Kidal and misses it terribly.

For Kaedi, loud and noisy Bamako is “worse than prison.” All he wants to do, besides play music, is return to the desert near his home, where “you don’t hear a motor for 20 days.”

The last two musicians introduced are quite different. Bassekou Kouyate plays an instrument called the ngoni and is in the centuries-old line of traditional griots.

By contrast, Master Soumy is a completely up-to-date rapper whose works include a song against Islam extremism, where he declaims lines like “murder and torture, explain your Islam.”

Though these musicians may be far from alike, they are all so disturbed by what is happening in their country that they join in a concert for peace. “It’s great to be an African,” one of them tells the audience. “It’s best to be a Malian.”

“Mali Blues” spends most of its time with Diawara, not only because she is as charismatic as any movie star (she, in fact, had a small role in “Timbuktu”) but also because her personal story of running away from home as a teenager to avoid a forced marriage is so compelling.

“I left to write my own story with my own pen,” is how she puts it. “I decided to face my own life in song.”

Easily the film’s most compelling section shows Diawara returning for the first time to the village where she was raised, her tumultuous welcome, and a song she performs to a women-only group in which she speaks out about the horrors of female circumcision, still very much an issue in the area.

“Mali Blues” ends on a happier note, with Diawara’s first-ever concert in Mali, at the riverbank Festival sur le Niger in Ségou. As in the entire film, the emotion is strong, the music joyous.

++++++++++++

‘Mali Blues’

No rating

Running time: 1 hour, 30 minutes

Playing: Laemmle’s Music Hall, Beverly Hills

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

Movie Trailers

ALSO

The best films of 2017 — so far. Here’s what our film critics think

After the buzz: Reflections of the last man to see ‘Get Out’ in a theater

Review: Bertrand Tavernier is an expert guide for ‘My Journey Through French Cinema’

Review: A man and an elephant take a road trip in quirky Thai comedy ‘Pop Aye’

Review: ‘Spider-Man: Homecoming’ trips on the teen angst, but Michael Keaton’s Vulture soars

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.